- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Monetary Policy

Six years into the expansion that followed the 2001 recession, the post-Y2K collapse of the stock market bubble, and the terrorist attacks, the economy is slowing and the risk of recession growing rapidly. After robust growth in mid-2007 of more than 4 percent, a sharp deceleration is unfolding. At best, we will narrowly skirt recession; at worst, we may already have entered one, given the inclination of the data to be revised. The risk of recession is already well over 30 percent, high enough that everyone should have a Plan B.

Headwinds are buffeting the economy: the collapse (from an unsustainable level) in housing construction; difficult credit conditions centered in but not limited to the subprime mortgage market; high energy prices; and falling home prices. All are taking a toll on the financial markets. With housing prices declining after growing far faster than incomes and rents, the booster shot to consumption from mortgage refinancing has slowed, and the wealth effect is turning negative. (Fortunately, most homeowners still have capital gains on their homes.) The possibility of avoiding recession depends on what might be called the “sector rotation gamble”: the hope that a pickup in net exports will cushion a likely slowdown in consumption and that capital spending will hold up fairly well.

There are some positive forces. Relatively more rapid growth abroad and the lower dollar are helping net exports. I expect growth abroad to slow as well. The notion that the rest of the world’s economies are now decoupled from the U.S. economy is overstated, and many of them have their own problems. A period of ambiguity and anxiety, with oscillating economic indicators, should be expected.

Neither the direct effect of the subprime interest resets nor the direct financial losses related to subprime lending are sufficient, even in combination, to cause a recession. For example, if 2 million households facing subprime resets reduced their consumption 25 percent, total consumption would decrease 0.3 percent. The consumption drag must extend far more broadly (perhaps because of declining home prices and high energy prices) to be a major macroeconomic event, as opposed to distress confined to a narrow group. And the $300 billion investor loss estimate from the mortgage crisis (as calculated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), which constitutes just half of 1 percent of net worth, might cause another small decline in consumption and investment. In a $14 trillion economy, such losses can be absorbed, but as much other financing is delayed (commercial and industrial lending and commercial paper outstanding are both down sharply), the harm will spread to the general economy and its firms and workers. That is what economic policy should aim to mitigate.

In the subprime case, collateralized subprime mortgages, increasingly originating with no income verification, little if any down payment, and very low starting teaser rates and therefore a “put” on the loan, were marketed as relatively safe bundles. The financial firms failed to adequately identify, price, and hedge the risk. Top executives at leading banks said they had not even heard of some of these complex structures before off-balancesheet loans went bad. Borrowing short in the commercial paper market and lending long to little or no equity might work for a while, but the risk should have been clear. The lack of transparency and risk management caused financial markets to lose confidence. Of course, subprime mortgages are unlikely to be the end of the story. For example, the same people who will struggle with mortgage interest resets have credit cards, the receivables from which are also collateralized. And prime mortgages and other nonmortgage lending are troubled.

What is the proper role of economic policy in dealing with these problems? Workouts, not bailouts. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulsen’s approach of convening mortgage servicers, originators, and investors to establish voluntary standards that facilitate constructive private sector workouts makes far more sense than taxpayer bailouts or the new regulatory proposals floating around Congress. But Paulsen should insist that it is voluntary, not imposed. The worst idea is a broad interest rate and/or foreclosure freeze for all borrowers, which would throw into question the very sanctity of private contracts and thus deter investment in these instruments, making them more expensive in the future.

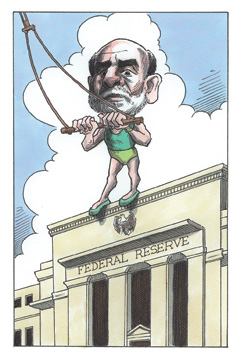

Ben Bernanke’s Fed has the delicate and difficult task of preventing recession while limiting the risk of subsequent inflation. The Fed led by Alan Greenspan brilliantly combated recession and ensured against deflation by quickly lowering the Fed funds rate to 1 percent and keeping it low; however, by eventually raising rates very slowly, even after the surge from the 2003 tax cut, it extended and worsened the speculative excess.

The Fed will and should be lowering rates to combat recession risks, although credit conditions will limit any stimulus. But its actions and communications must reinforce the commitment to price stability so as to maintain confidence and credibility. The worst outcome would be the small but real possibility of future inflation pressure.

Even worse policies could be just around the corner. Calls for protectionism and for more regulation and higher taxes on upper-income earners and capital are emanating from Capitol Hill and the campaign trail. Some of these calls are even demonizing globalization and corporate America. This doesn’t build confidence in the future of the economy. It was this poisonous policy mix (along with the Fed’s mistakes) that turned a bad downturn into the Great Depression.

At a debate among the economic advisers to the presidential candidates in Washington in November, the advisers to the Clinton, Obama, and Edwards campaigns lauded soft- or hard-core protectionism, higher marginal tax rates, uncapping Social Security taxes, a bevy of new spending programs, and refundable tax credits for every perceived problem, and argued that the Bush tax cuts were the cause of all economic ills. That represents bad economics and even worse history.

The fundamental flaw in that approach is the unwarranted assumption that it would help the middle class. Of course, it would create some temporary relief, but at the cost of lower future wages from the depressed capital formation and a risk of dependency on ineffective, inefficient government programs. The Europeans’ mediocre economic performance attests to the danger of high taxes and bloated social-welfare spending, which in little more than a generation have driven down their standard of living 30 percent relative to the United States.

Revoking the 2001 and 2003 top marginal tax rate reductions, uncapping Social Security taxes, and adding the proposal by House Ways and Means Chairman Charles Rangel for an additional 4.6 percent tax rate on adjusted gross income as part of his AMT fix would triple the federal taxes on dividends, almost double the tax on capital gains, and sharply reduce work and investment incentives. The combined top marginal tax rate (including California state taxes) would reach almost 70 percent, back to the ruinous levels of the 1970s.

The tax share of GDP, already somewhat above the historical average, rises automatically in normal economic times and is scheduled to reach about 20 percent—a level reached only during wars, bad inflation, or bubbles— in a few years. It would reach about 24 percent in a couple of decades because of real bracket creep, the alternative minimum tax, the expiration of the tax cuts, and other factors.

The long boom of the past quarter-century was fostered by low inflation and low tax rates. Sound policy requires stringent control of spending growth and calls for large legislated tax reductions focused on marginal personal and corporate income tax rates. That change is essential for long-term growth. It should be legislated now to help restore confidence and investment in the future, especially as the economy weakens, above and beyond whatever short-run fiscal stimulus may be enacted.