In 1945, demurring from Roosevelt and Churchill’s consignment of Poland permanently to Soviet hegemony, Charles de Gaulle wrote in Vol. III of his memoirs that it is imprudent to foreclose the possibility of any nation’s renewal because “the future lasts a long time.” Nevertheless, while it is impossible to say whether another Europe in another era will acquire significant military capacity, we can “bet the farm” that this Europe won’t, because it has become intellectually, morally, and politically incapable of it.

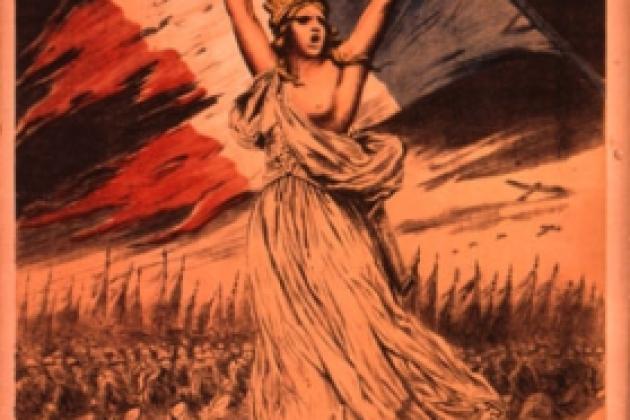

This Europe differs substantially from the one that emerged from World War II, which the Hoover Institution’s Peter Duignan and Lewis Gann described magisterially in The Rebirth Of The West. That Europe armed itself against the Soviet Union because it was committed morally to Christian civilization and politically to the nationalism it had inherited from the 19th Century. Catholic statesmen set the tone of that relatively potent “Europe des Patries”–France’s de Gaulle and Robert Schumann, Germany’s Konrad Adenauer, and Italy’s Alcide de Gasperi. The Franco-German treaty codified it in 1963.

The U.S. government bears some responsibility for replacing that Europe with a congenitally impotent one. In 1956 The Soviet Union had threatened war against Britain and France for their military assertion of their ownership of the Suez Canal. The U.S. government joined the Soviets in condemning them. This, combined with U.S. support for the Arab revolt in France’s Algerian departements (and America’s 1954 abandonment of France in Indochina) helped convince the British and French that they should divest themselves of their overseas territories and of the conventional forces they had used to hold them.

Beginning in 1961, the Kennedy Administration began to constrain Britain’s and France’s nuclear forces. Kennedy withdrew cooperation from the Skybolt project, which would have extended the life of Britain’s bombers. Then it pressured Britain to scrap its missile-firing submarines in favor of purchasing American ones. At the same time, it discouraged, denigrated, and derided France’s own wholly indigenous nuclear force, often in scatological terms. This undercut support for such forces in Europe.

In 1962, under the not-so-secret agreement that ended the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy withdrew U.S. intermediate range missiles from Britain, Italy, and Turkey, discrediting the European leaders who had staked their reputations on their importance. This happened as the Administration replaced America’s commitment to strike the Soviet Union should it ever invade Europe with the highly unpopular vow to fight such an invasion on European ground. This set off the Atlantic Crisis ably chronicled by Robert Kleiman’s 1964 book of that name.

The Kennedy Administration’s refusal to uphold the West’s right of access to all of Berlin, and its acquiescence in the maintenance of the Berlin Wall, completed the discrediting of post-war Europe’s leadership and opened the door to a new leadership with wholly different priorities. Whereas in 1959 Germany’s Socialist Party had made a historic commitment to the West, by 1962 it was leading Europe in pressing for disarmament and concessions to the Soviets. By 1961 the sense that the U.S. would not resist the Soviet Union–and the U.S. government’s urging–led Italy’s governing coalition to include the Communist party’s proxies.

Within a decade, the turnover of Europe’s elites was well nigh accomplished. As Plato pointed out, any polity is the “writ large” version of those who set its tone. The “generation” that has occupied the commanding heights of European government, economics, and above all of culture, since roughly 1968 largely fulfilled the ambition of “hegemony” that Antonio Gramsci had outlined in his Prison Notebooks (1929-1935). That “hegemony,” far more totalitarian than anything Lenin imagined, rests on Machiavelli’s insight that the seizure of power over language and other cultural standards can be made irreversible.

That is why Europe’s ruling class does not worry about the region’s economic problems, never mind its demographic ones. Although native populations in free fall are being replaced by persons who are less immigrants than occupiers, and the region’s bloated public sectors are surviving only by pauperizing those outside, the ruling class is confident that no alternative threatens it. Though few can imagine how Europe’s current way of life can be sustained, fewer yet entertain politically incorrect thoughts about changing it.

On the contrary, Europe’s cultural elite seems preoccupied with further entrenching its Gramscian hegemony. As usual, France is in the lead. Jean-Marie Guehenno’s The End Of The Nation State (1993), arguably this generation’s most influential intellectual product, argues that modern Europe has developed a political model superior to that of the nation state and a cultural one superior to that of the Christian religion–“an ensemble of rules with no other basis than the daily administered proof of its smooth functioning,” and “a religion without god” based on “a world of rituals” that “represent in the world of things what priests do in the world of gods.” “Ritual prevails over metaphysics.”

These abstractions become concrete. France’s Minister of education, Vincent Peillon, explains in his book The French Revolution is Not Over (2012) that the educational establishment’s job is to “invent a Republican religion.” The schools must be a “new church with its new ministers, its new liturgy and its new tablets of law.” No need to guess whose wealth and power this religion serves.

It is impossible to imagine how thoughts about military defense of a nation’s common good might fit into minds that reject the very notion of nations, of objective good and evil, and whose concrete concerns are limited to enhancing their own hegemony.