- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- World

- Science & Technology

- History

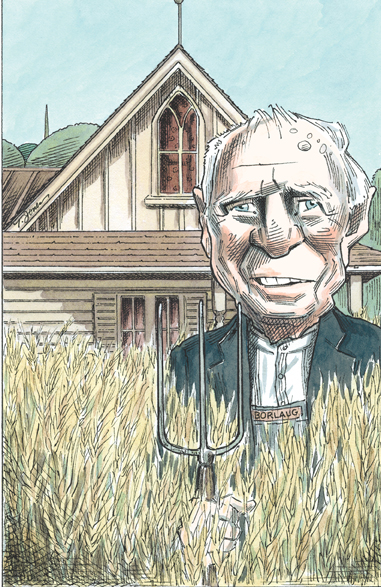

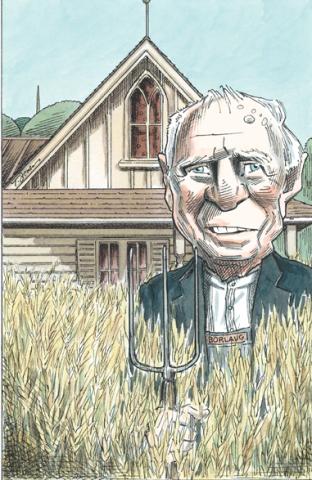

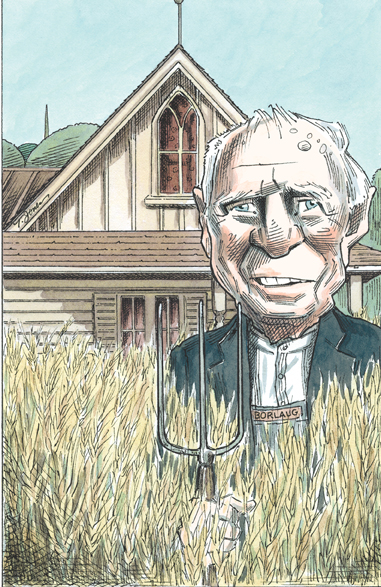

My friend Norman Borlaug, the plant breeder known as the Father of the Green Revolution, passed away recently at the age of 95. His life was one of extraordinary paradoxes: a child of the Iowa prairie during the Great Depression who attended a one-room school, aspired to become a high school science teacher but flunked the university entrance exam, yet went on to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for a series of agricultural innovations that averted malnutrition, famine, and the death of millions.

Norman combined science, common sense, and plain old hard work. First, he and his colleagues laboriously crossbred thousands of wheat varieties from around the world to produce new ones with resistance to rust, a destructive plant pest, thus raising yields by 20 to 40 percent.

Second, he crafted so-called dwarf wheat varieties that would not fall over in the field when aggressively fertilized so as to achieve maximum yields.

Third, he devised an ingenious technique called shuttle breeding—growing two successive plantings each year, instead of the usual one, in different regions of Mexico. The availability of two test generations of wheat each year cut the years required for breeding new varieties in half. Moreover, because the two regions possessed distinctly different climatic conditions, the new early-maturing, rust-resistant varieties could be broadly adapted to many latitudes, altitudes, and soil types. Such wide adaptability, which flew in the face of agricultural orthodoxy, proved invaluable, and Mexican wheat yields skyrocketed. Similar successes followed when the Mexican wheat varieties were planted in Pakistan and India, but only after Norman persuaded politicians in those countries to change their national policies to provide the large amounts of fertilizer needed for wheat cultivation.

His work resulted in high-yielding varieties of wheat that transformed the ability of Mexico, India, Pakistan, China, and parts of South America to feed their populations. In his professional life, however, Norman struggled against prodigious obstacles, including what he called the “constant pessimism and scaremongering” of critics and skeptics who predicted that despite his efforts, mass starvation was inevitable and hundreds of millions would perish in Africa and Asia.

How successful were Norman’s efforts? From 1950 to 1992, the world’s grain output rose from 692 million tons from 1.70 billion acres of cropland to 1.9 billion tons from 1.73 billion acres—an increase in yield of more than 150 percent.

Without high-yield agriculture, either millions would have starved or increases in food output would have been realized only through drastic expansion of land under cultivation—with losses of pristine wilderness far greater than all the losses to urban, suburban, and commercial expansion.

Norman recalled to me without rancor the maddening obstacles to the development and introduction of high-yield plant varieties: “bureaucratic chaos, resistance from local seed breeders, and centuries of farmers’ customs, habits, and superstitions.”

Both the need for additional agricultural production and the obstacles to innovation remain; in his later years, Norman applied himself to ensuring the success of this century’s equivalent of the Green Revolution: the application of gene splicing, or genetic modification, to agriculture. Products in development offer the possibility of even higher yields, fewer inputs of agricultural chemicals and water, enhanced nutrition, and even plant-derived, orally active vaccines.

Extremists in the environmental movement, however, are doing everything they can to stop scientific progress in its tracks, and their allies in national and United Nations–based regulatory agencies are eager to help. Norman saw history repeating itself: “At the time [of the Green Revolution], Forrest Frank Hill, a Ford Foundation vice president, told me, ‘Enjoy this now, because nothing like it will ever happen to you again. Eventually the naysayers and the bureaucrats will choke you to death, and you won’t be able to get permission for more of these efforts.’ Hill was right. His prediction anticipated the gene-splicing era that would arrive decades later. . . . The naysayers and bureaucrats have now come into their own. If our new varieties had been subjected to the kinds of regulatory strictures and requirements that are being inflicted upon the new biotechnology, they would never have become available.”

Norman observed that the enemies of innovation could create a self-fulfilling prophecy: “If the naysayers do manage to stop agricultural biotechnology, they might actually precipitate the famines and the crisis of global biodiversity they have been predicting for nearly forty years.”

Norman’s story is a saga of the greatness of America during the twentieth century—of opportunity, individuality, courage, and achievement. He strove to exploit new technology based on good science and good sense.

As remarkable as Norman’s scientific and humanitarian accomplishments were, his friends will remember him as well for his modesty, guilelessness, and kindness. Norman’s modus vivendi might be summed up in the observations he made about the importance of food and the application of science to feeding the hungry:

First: “There is no more essential commodity than food. Without food, people perish, social and political organizations disintegrate, and civilizations collapse.” Second: “You can’t eat potential.” In other words, you haven’t succeeded until you get new developments into the field and actually into people’s bellies. Finally: “It is easy to forget that science offers more than a body of knowledge and a process for adding new knowledge. It tells us not only what we know but what we don’t know. It identifies areas of uncertainty and offers an estimate of how great and how critical that uncertainty is likely to be.”

How to capture the essence of Norman Borlaug? I’m reminded of a line from a poem by Matthew Arnold, who described Sophocles as a man “who saw life steadily, and saw it whole.”