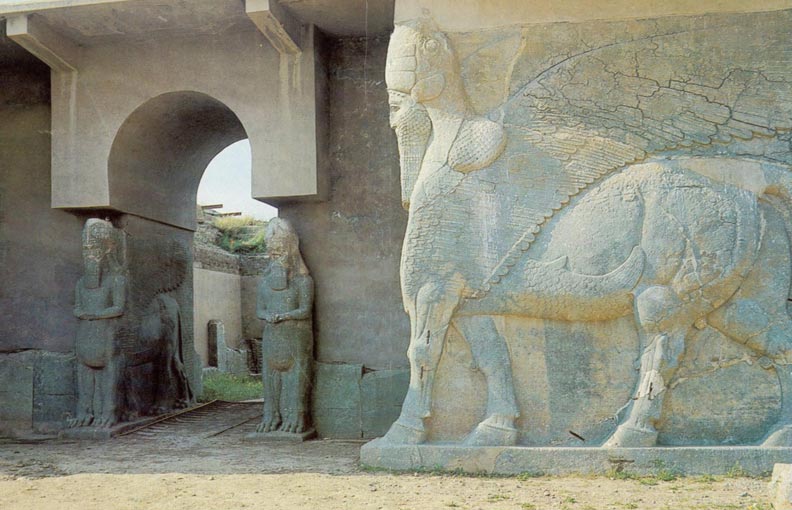

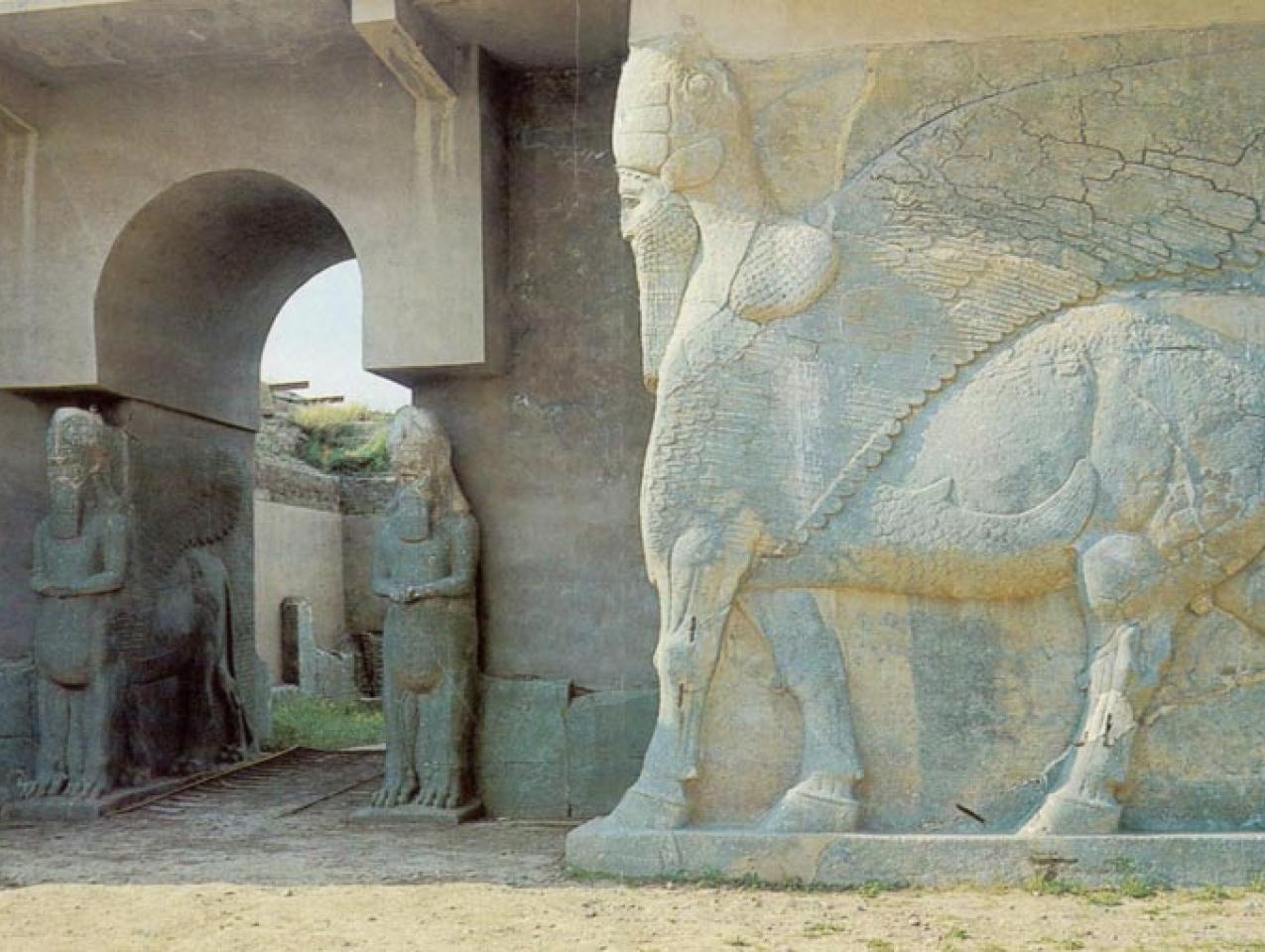

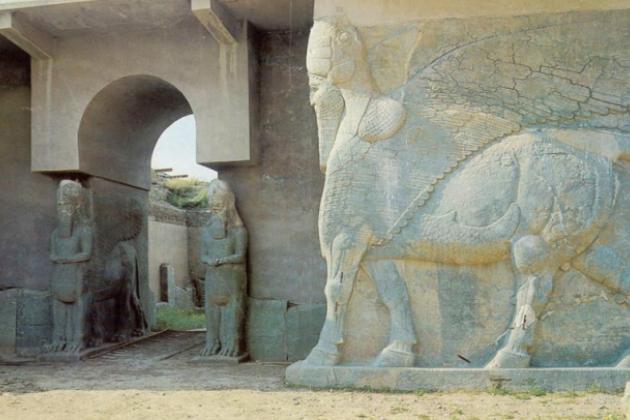

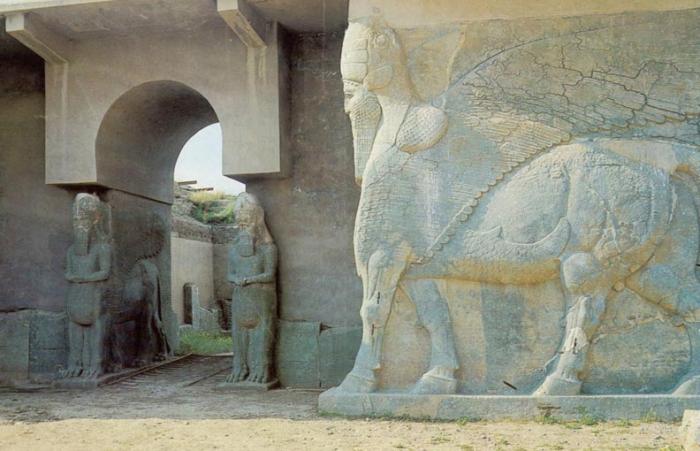

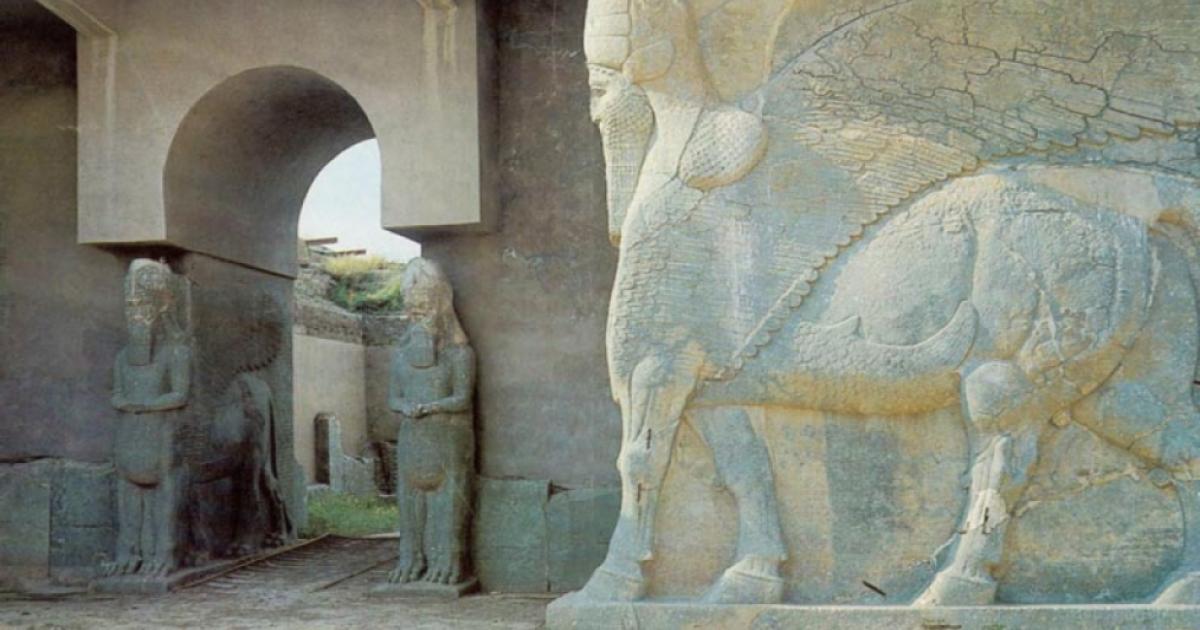

Scenes of Islamic State mauls smashing ancient statues—one a winged bull from ninth century, B.C. Assyria—in the museum of Iraq’s northern city of Mosul and in the ancient city of Nimrud, reveal a new and profound dimension in radical Islam’s twenty-first century war on world civilization. When the slaughter, enslavement, and genocidal designs on other religious groups are joined by culturally catastrophic destruction of non-Islamic arts and artifacts, then the world faces a fully totalitarian enemy whose rationale is directly declared: “Oh, Muslims, these artifacts that are behind me were idols and gods who lived centuries ago [and were] worshipped instead of Allah,” the smasher said to the camera. “Our Prophet,” he continued, “ordered us to remove all these statues as his followers did when they conquered nations.”

Such cultural devastation has been evident all across this new twenty-first century, from the Taliban’s mortaring and dynamiting the giant sculpted Buddhas carved into the rock face at Bamiyan on the ancient Silk Road through Afghanistan to the Islamist devastation of the mausoleum, shrines, and library of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Muslim center of learning at Timbuktu, a registered world cultural heritage site. The devastation is also apparent in Saudi Arabia’s systematic destruction of the traditional surroundings of the Ka’aba and the Grand Mosque of Mecca. The government has obliterated significant Ottoman-era structures to put up high-rise glass and steel hotels of indistinguishable modern facelessness, a demonstration that such cultural ravages can be carried out by legitimate, internationally-recognized Muslim state regimes as well as by the radical jihadis who aim to overthrow those same state regimes as abominations in the eyes of Islamism.

If these depredations of Islamism are an atavistic reawakening of the seventh-century Islamic rise in order to command the future, it is necessary to review the devastations generated by the modern age itself all through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. With the Enlightenment, as Kant and Hegel made clear, history replaced theology and religion as the arena in which the greatest challenges of the human condition would have to be played out.

With religion relegated to the sidelines, ideology was invented as its substitute. Ideology became a totalistic, answer-all-questions compulsory atheistic faith. Like most religions, once inaugurated, the ideology begins the world anew: the French Revolution as the year zero or Mao’s Tiananmen architecturally declaring that nothing good happened before 1949. Thus history itself was destroyed or transformed with a scientific certainty, a railroad along which the ideology would inevitably ride.

The zenith of ideology’s catastrophic destruction of culture came in Mao’s Cultural Revolution, launched to totally eradicate traditional Chinese culture by burning books, outlawing the Peking Opera and all theatrical productions, suppressing academic and intellectual life, and tearing down pagodas and temples. Any structure or creative arts manifestation had to be destroyed. All this was produced in accordance with Mao’s perception that Marxism had to be turned upside down. Materialism, the economic base that, when communized, was supposed to change the culture, had not worked. Mao saw culture—and he was correct—as the determinative human factor, so China’s great cultural past had to go. Confucius was reviled; Mao reveled in being compared to China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, who burned the books and buried scholars alive.

What we are witnessing today in Islamism’s war on the world’s cultures is not unconnected to this modern revolutionary upheaval. The “history” that replaced religion in the Enlightenment and which was in turn commandeered by ideology, has with the Islamic Republic of Iran’s revolutionary seizure of state power in 1979 and the Islamic State’s taking extensive territorial power in 2014-15, amalgamated religion and ideology as a new stage in the war against history. No wonder, therefore, that the radical jihadists revel in their conviction that the ultimate apocalyptic moment has been placed in their hands.

However grotesque and despicable is Islamist vandalism in the service of imagined divine instructions, there is more at stake in this phenomenon. Something of world-historical consequence is going on, because this jihadi assault threatens a global development which may stand comparison with the “Axial Age,” a transformation in human consciousness discerned by the philosopher Karl Jaspers (1885-1969): that in the middle centuries of the first millennium B.C. a trans-civilizational shift in mentalities took place across a great swath of the globe from the Eastern Mediterranean to Persia to South Asia to China. Sharply contested, the axial theory nonetheless does provide coherence to the emergence of cultural expressions that contain both individualist and universalist characteristics at the same time. A “New Axial Age,” which can at least hypothetically be tracked from the early Modern age to the present, is still in an emerging phase of development, one that centers on cultural art and artifacts.

Start with the reality that the sixteenth-century Reformation, a key moment in the history of modernity, produced religiously driven iconoclasm; a smashing of the images, altars, and sculptures on the grounds that such “idolatry” had caused humanity to be afflicted by the wrath of God.

The 1648 Westphalian settlement of the Thirty Years’ War—a war of religions—would subdue this inclination to cultural mayhem by gaining an informal international understanding that religious convictions should be sidelined when it came to diplomatic negotiations among states. The Treaty of Westphalia would lead to an international system based on procedural rather than substantive requirements; it thus could, and did, evolve into a light structural framework for interactive world affairs while leaving each nation’s culture, religion, and politics legitimately its own business.

Countervailing events followed. Lord Elgin (the 7th Earl) in the early 1800s removed the marble sculptures from the Parthenon to England for safe keeping in the British Museum—otherwise, they certainly would have been destroyed. Lord Elgin (the 8th Earl) invaded China and burned and plundered treasures of the Summer Palace for the larger purpose of forcing the Qing court to accept the procedures—resident ambassadors—of the Westphalian international state system; this was certainly a cultural crime of great magnitude.

Yet a parallel and positive cultural course was also emerging. British scholar-adventurer-archeologists discovered lost or discarded sites and images of the Buddha in northern India; it is not too much to say that Buddhism itself might have vanished without this project and subsequent British preservation and interpretation of ancient Buddhist scrolls. A similar story can be found regarding Islam, as in Oxford University’s study of the Amiriya at Rada, a sixteenth-century madrasah in Yemen, the archeological interpretation of which revealed commercial-religious-civilizational contacts between India and the Arabian Peninsula. And some cultural scholarship and preservation efforts were cross-culturally collaborative, notably the use by Chinese scholars of Western training and techniques gained at the University of Pennsylvania to initiate the study and preservation of China’s architectural heritage, identifying the T’ang dynasty era wooden Buddhist temple in the Wu Tai mountains, later a victim of Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Such measures were accompanied by the Western institutionalization of the museum, an idea as old as fifth-century B.C. Delphi but emerging as a globe-spanning phenomenon in the modern eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, places where an unlimited diversity of works of art would be gathered and available to the public as the object of study and comparison for an ever-greater understanding of mankind. Here was Edmund Burke’s definition of the social contract: a partnership between the dead, the living, and those yet to be born, a gain for the common good of all humanity.

Notable figures in modern intellectual history caught the importance of this expanding mosaic of the art works of the world’s cultures. How could Edmund Burke be for the American Revolution and against the French Revolution? The answer is that each culture must be seen as its own intelligible field of study. In describing the American whaling ships and crew, Burke notes that while seemingly indistinguishable from the English, the Americans had formed their own unique culture. Like the ancient Athenians, “they were born to take no rest and to give none to others” and so were ungovernable from London. In contrast, the French Revolution had torn off “all the decent drapery” of French culture and replaced it with blood running in the gutters, hangings from lampposts and, to come, a military dictator on horseback. As for India, the historian Macaulay described Burke’s appreciation for Indian culture and the impact he made on the House of Commons:

India and its inhabitants were not to him, as to most Englishmen, mere names and abstractions, but a real country and a real people. The burning sun, the strange vegetation of the palm and the coca tree, the rice-field, the tank, the huge trees, older than the Mogul empire, under which the village crowds assemble, the thatched roof of the peasant’s hut, the rich tracery of the mosque where the imaum prays with his face to Mecca, the drums, and banners, and gaudy idols, the devotee swinging in the air, the graceful maiden, with the pitcher on her head, descending the steps to the river-side, the black faces, the long beards, the yellow streaks of sect, the turbans and the flowing robes, the spears and the silver maces, the elephants with canopies of state, the gorgeous palanquin of the prince, and the close litter of the noble lady, all these things were to Burke as the objects which lay on the road between Beaconsfield and St. James’s Street. . . . Oppression in Bengal was to him the same thing as oppression in the streets of London.

Here may be sensed the opening of a “New Axial Age,” a general elevation of consciousness that the great civilizations of the world, however remote to each other in time and place, each expressed in its art, literature, philosophy, and spirituality some foundational truths of the human condition of all.

Ralph Waldo Emerson explicitly caught this new age in his essay, “History.” Emerson realized that it now was possible, for the first time ever, to survey something close to the full range and corpus of history’s multiplicity of civilizations across time and place. He and Thoreau already had been sending away for boxes of the classic texts of India (e.g. The Rig Veda) and China (Confucius’s Analects). These works made a powerful impact: “How easily these old worships of Moses, of Zoroaster, of Menu, of Socrates, Domesticate themselves in the mind. I cannot find any antiquity in them. They are mine as much as theirs.” Here Emerson is conducting a reconnaissance of the works of the first Axial Age to set forth a manifesto for the new Axial Age:

There is ONE MIND common to all individual men…. Who hath access to this universal mind is a party to all that is or can be done…. Of the universal mind each individual man is one more incarnation.

So the opportunity and responsibility presented by the new availability of the world’s vast diversity of thought is to encounter these works as a whole and remake, retell them of oneself; not to be guided by them but to write our own annals broader and deeper: “I have no expectation that any man will read history aright, who thinks that what was done in a remote age, by men whose names have resounded far, has any deeper sense than what he is doing today.”

What Emerson understood as the incorporation and reworking of creative thought in philosophy, literature, and metaphysics would be recognized in the visual arts as well. Walter Benjamin analyzed it negatively in his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” The ubiquity of reproductions of past works of great art, Benjamin wrote, deprives them of their unique authenticity in time and space; deprived of context, they lost their aura and authenticity too.

André Malraux, the French adventurer, novelist, and Minister of Culture in the time of Charles de Gaulle, gave the phenomenon a positive turn, doing for works of art what Emerson had done for written classics. In his “Museum Without Walls,” he granted that the effect of the museum was “to divest works of art of their functions. . . other than that of being a work of art.” But “the assemblage of so many masterpieces—from which, nevertheless, so many are missing—conjures up in the mind’s eye all the world’s masterpieces.” Malraux elaborates: “It is in terms of a world-wide order that we are sorting out, tentatively as yet, the successive resuscitations of the whole world’s past … with the result that a large share of our art heritage is now derived from peoples whose idea of art was quite other than ours, and even from people to whom the very idea of art meant nothing.”

The next phase of recognition comes serendipitously in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Bulletin depicting a selection of “Recent Acquisitions.” A random selection makes the point that a new realm of consciousness has opened and calls for new interpretations:

- “Lakshmi, Goddess of Prosperity, India, Late 7th century;

- Wall Painting, Mexico, 650-750;

- Appliqued Quilt, Illinois, ca. 1875

- Shia Processional Standard for the martyrdom of Husain, ca. 1700;

- Head of Demosthenes, Roman, 2nd century A.D.:

- Photograph: Sojourner Truth, 1864

To move back and forth across these images is to encounter the world’s cultures at a new level and scale for study by the humanities. The selection amassed has a meaning of its own, yet the real object, its museum context, its provenance, originating story, and particular civilizational significance draws us in. The destruction of any one of these objects is an attack not only on its own unique meaning but also on the newly emerging potential for a deepened understanding of humanity through comparative art.

There is a democratic dimension as well. Democracy within a state is essential for human freedom and cultural flourishing; the more democracies the better. A consensus holds, however, that the international system with its organizations and processes, cannot and should not be democratic; “global governance” would suffocate a nation’s cultural expressions. But the international heritage in art works is otherwise, because the artist is individual and aesthetic assessments cannot be confined or dictated; Stalinist, Nazi, and Maoist attempts to do so were risible and rejected. Thus the “new axial” possibilities are democratic in an international way that government cannot commandeer. Artistic and political freedoms go together; their deadly, Dark Ages-bringing enemy is the sledgehammer.