- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

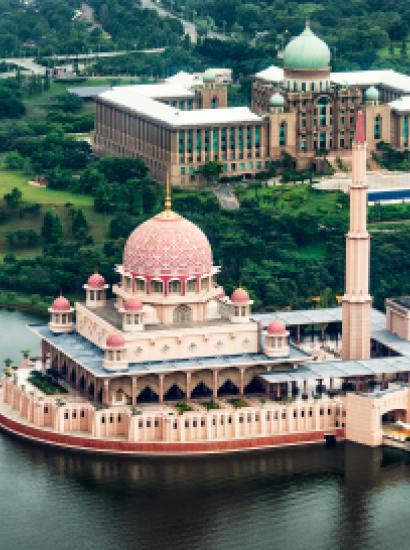

The rise of radical Islam in the Middle East over the past few decades now may be reaching the Far East. This appears along a scale of seriousness from new levels of political concern to the reality of enhanced tensions and violence from west to east along an archipelago of national territories from Thailand’s Isthmus of Kra, down the Malaysian peninsula into Indonesia’s Sumatra, Java, and eastern islands, and up into Mindanao in the Philippines. Taken together, indeed with Indonesia alone, these lands hold by far the largest Muslim population in the world.

Islam has been a significant factor in this region for at least seven centuries, yet in a longer and larger global geostrategic perspective, Southeast Asia comprises a uniquely varied and extensive range of ethnic, historical, economic, cultural, and psychological dimensions beyond that of any other single area of the world:

- The ancient Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms whose religions and cultural heritage has persisted and may be in a new period of revival;

- The political legacies of Dutch, British, and Spanish imperialism and colonization;

- The Second World War’s Imperial Japanese occupation, proclaimed as Asia’s liberation from colonialism, but in fact replacing one form of foreign dominance with another;

- The ideological and radicalized remnants of Cold War communist guerilla insurgencies, begun to overthrow European colonial rule, then continued in attempts to overthrow nationalistic post-colonial governments;

- The ubiquitous economic and interconnected presence of the “Overseas Chinese,” whose generations of arrivals preceded Europeans by centuries, first as merchants, then common laborers, workers in foreign-run mines and plantations, and often in business cooperation with foreign enterprises. The flow of their remittances made this diaspora significant to one Chinese dynasty or regime after another. Generally remaining apart and only nominally assimilated, they established “Chinese Quarters” in major cities, and operated through “secret societies.” As a result, the Overseas Chinese periodically were discriminated against, but accumulated wealth and power nonetheless.

Also involved at present are the strategic ambitions of the People’s Republic of China as revealed in its recent seizure and militarization of shoals and reefs in the South China Sea and its interests in the “choke points” of the Strait of Malacca, the Sunda Straits and the maritime approaches to the critical periphery of global interactions along coastal Vietnam and Borneo to the east, and down the Burmese panhandle on the Andaman Sea to the West.

China’s strategic actions in and around the waters of Southeast Asia cannot but be of concern to the United States and to the international system’s responsibilities to maintain freedom of the seas and related principles of international law.

All these factors affect the sovereignty and integrity of Southeast Asian nations. Along with fears of foreign encroachment have come questions of loyalty within domestic contexts. European colonialists were loyal to their far-off central governments; Overseas Chinese were considered subjects of the Qing dynasty, and later as vanguards of Mao’s version of international communism; today they are claimed by the People’s Republic of China regardless of what other citizenship they may hold.

Muslims, arriving as early as the fourteenth century, spread the faith not by the sword but by traders accompanied by Mughal, Ottoman and Arab teachers of Islam, making it clear that they recognized the sovereignty of Allah, not local governing authorities. The twentieth century’s most influential anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, observed that, “In Indonesia Islam did not construct a civilization, it appropriated one” and maintained its attachments to another, wider world of commerce, politics, and belief through the immense number of pilgrims making the Hajj to Arabia every year.

This was vividly depicted in one of the modern classics of literature, Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, 1899, based upon an actual catastrophe of 1880 when the ship Jeddah, named for the Arabian Red Sea port near Islam’s Holy Mosque of Mecca, after taking aboard at Penang, Indonesia, over 900 pilgrims making the Hajj, was devastated by a storm at sea so severe that her boilers were torn from their fastenings. The captain, assuming his ship was doomed, lowered one of the few lifeboats and abandoned his command, taking his wife, first mate, and engineer with him. When eventually rescued by a British vessel they would learn that the Jeddah in fact had not sunk and that his dereliction of duty was known to all. In Conrad’s novel, the ship is named Patna whose Captain Jim will spend the rest of his life in ignominy, seeking to atone for his cowardice toward the Muslims under his protection.

The question today for Southeast Asia involves the extent to which culture affects the spread of Islam. Is there something in Arabian culture which radically incites potential adherents to regard violence as essential to the faith? Is there something in the cultures of Southeast Asia that provides a predisposition to hold more easily to Islam as a religion of peace?

According to Geertz, writing some fifty years ago, Indonesian Islam has been “at least until recently, remarkably malleable, tentative, syncretistic, and most significant of all, multi-voiced.” In Indonesia, Islam has taken many forms, not all of them Koranic, and whatever it brought to the sprawling archipelago, it was not uniformity.” Today, Islam in Indonesia may have come “to what may, without any concession to the apocalyptic temper of our time, legitimately may be called a crisis “over what those who call themselves Muslims actually believe.”

In this context, two cases of conflict in the region stand out:

One is Aceh, the northwest tip of Indonesia’s Sumatra, the place where the Islamification of Indonesia began over six centuries ago. Rigidly Islamic and relentlessly restive or rebellious against outside authority, Aceh was more at war than peace after the Dutch attempt to subdue the Sultanate in 1873.

After suffering unprecedented devastation from the tsunami of 2004 and then experiencing the benefits of international disaster relief efforts largely managed by the U.S. Navy, a UN-negotiated peace agreement was reached through which Indonesia recognized Aceh’s autonomy and formal imposition of Sharia law as Indonesian national forces would withdraw and Aceh’s rebellious militia would disarm. The tense relation of autonomy to national sovereignty has not however disappeared as Sharia-required caning of offenders in public have raised protests from human rights activists beyond Aceh’s borders.

The other case is Mindanao, the southernmost part of the Philippines where, in the 15th century, Muslim settlers and proselytizers arrived from Johore to spread the faith. From Mindanao they moved north to Luzon where their advance was blocked by the Spanish rulers of the Philippines who denounced them as “Moros,” akin to the “Moors” of Al-Andalus, Islamic Spain, who had been ousted from Iberia by the “Reconquista.” Centuries later the Moros would fiercely battle American forces that arrived to take control of the Philippines from Spain following the U.S. victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898 in Cuba. Across the centuries the Moros have been engaged in one form or another of revolt against the national government in Manila and have adopted jihadist tactics of terrorism and beheadings. The fighting at present in Mindanao is fiercer than ever, and U.S. Special Forces have been involved in support of the Filipino government.

How this regional challenge in its present form will be met may determine whether the Southeast Asian nations will or will not become a widening sector of the 21st century’s Islamist war now waged in the Middle East and in various forms elsewhere in the world.

Bibliography

John King Fairbank, Edwin O. Reischauer, and Albert M. Craig, East Asia: the Great Transformation. Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

Mapping the Acehnese Past, Feener, Daly, Reid, eds. Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal, Land-en Volken kunde, 2011.

Clifford Geertz, Islam Observed: Religious Development in Morocco and Indonesia, Yale University Press, 1968.

Stanley Karnow, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines. Ballantine Press, 1989.

V.S. Naipaul, Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey, Knopf, 1981.

Witness to Sumatra: A Traveler’s Anthology. Ed. Anthony Reid. (Oxford in Asia) Oxford University Press, 1995

Eric Tagliacozzo, Secret Trades, Porous Borders: Smuggling and States Along a Southeast Asian Frontier, 1865-1915. Yale University Press, 2005.

Gavin Young, In Search of Conrad. Penguin, 1992.