- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

Last July, Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney invited the ridicule and wrath of the world’s politically correct during a visit to Jerusalem. Culture, he said, seriously impacts the prospects for economic and political development in Palestine and the Arab world. A senior aide to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas immediately branded Romney’s remarks “racist” and insisted that Palestine’s only problem with development is the Israeli occupation.

But if one looks beyond the equally critical media headlines, Romney and the Harvard emeritus economist and historian David Landes, whom he cited, turn out to have an army of unexpected allies in the Arab world. Between 2002 and 2009, the United Nations Development Program published the five-volume Arab Human Development Report (AHDR) drawn up by more than a hundred Arab scholars and experts.

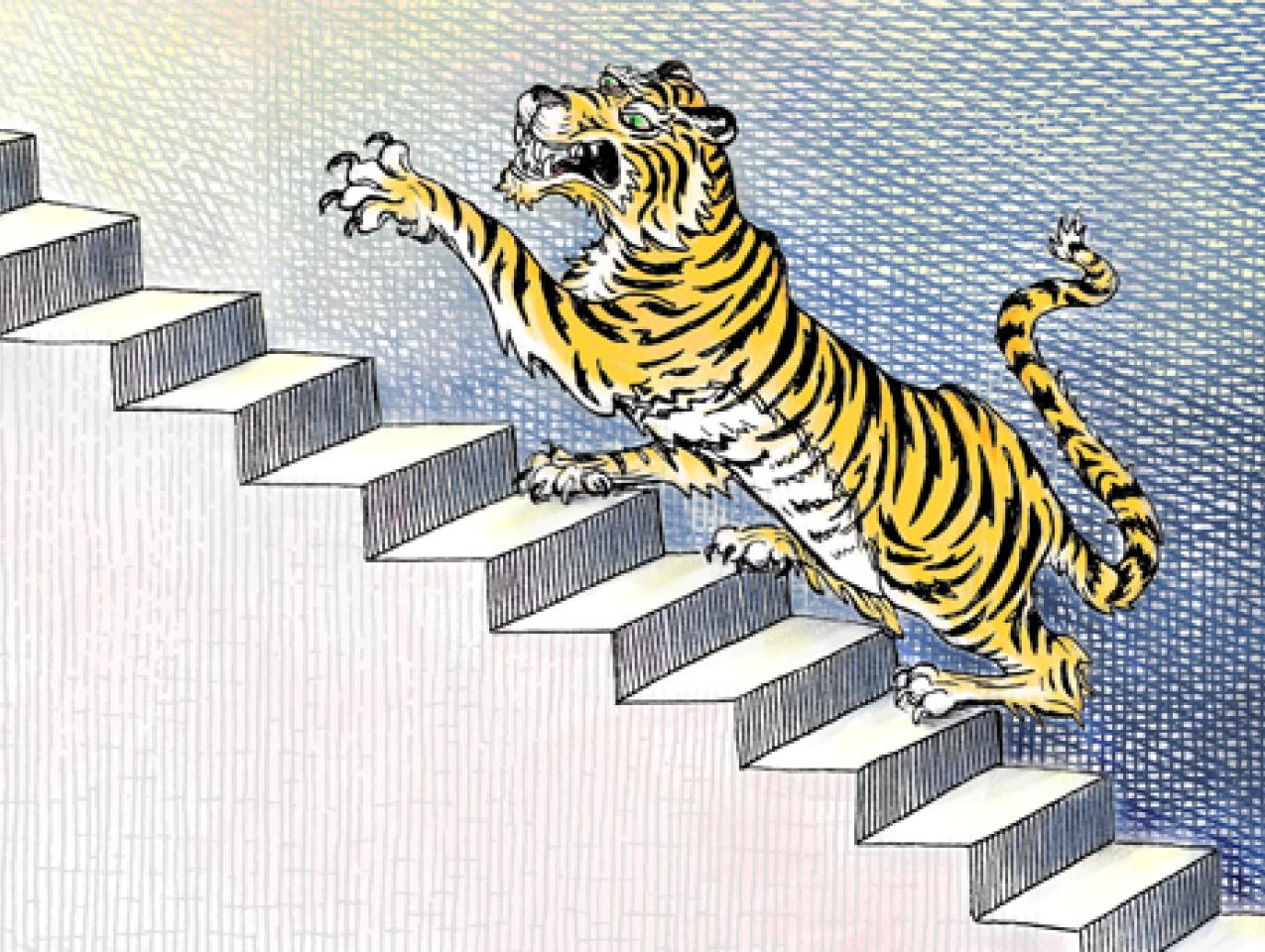

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

The 2002 AHDR states that “culture and values are the soul of development…They provide its impetus, facilitate the means needed to further it, and substantially define people’s vision of its purposes and ends.” A foreword adds, “the predominant characteristic of the current Arab reality seems to be the existence of deeply rooted shortcomings [that]…pose serious obstacles to human development.”

Of course many factors contribute to a country’s poverty or prosperity, including the quality of its leadership, its economic orientation, and the absence or presence of effective legal and other governing and regulatory institutions. Some lessons can be harvested from history; others can be learned from neighbors; still others can be discovered by informed trial and error. It is also true that some countries face far greater developmental challenges than others, thanks to the vagaries of history and geography.

Still our self-inflicted blindness on the role of culture in history and current affairs is one reason why so many Western commentators had such unrealistic expectations about the “Arab Spring.” The emergence, prominence, and ideological orientation of the Muslim Brotherhood in a democratic Egypt, for example, were as predictable as tomorrow’s sunrise on the Sahara. And though democratically elected, there is so far little reason to believe that the new government in Egypt—or those that may arise in other Arab countries—will undertake the tough long-term reforms that would move them into the developed world, nor indeed that that is what the bulk of the voting population most wants from them.

Culture and Development

If we look at history and the modern world, we find culture plays a major role in how countries develop. Culture is that mix of values, beliefs, attitudes, commitments, and motivations that are shared by most or at least the predominant members of a society and, in many respects, it guides their thinking and actions. Nobel Prize-winning economist Douglass North said culture is “collective learning—a term used by Hayek—[which] consists of those experiences that have passed the slow test of time and are embodied in our language, institutions, technology and ways of doing things.”

There are two main reasons why culture is often viscerally rejected as an explanation of development. The first was noted by economist David Landes when he wrote that “criticisms of culture cut close to the ego and injure identity and self-esteem.” Certainly no comments here are meant to insist that one civilization is more virtuous than another, but simply to observe that people in one civilization often see and do things differently from those in other civilizations and those differences often have tangible consequences.

Secondly, many economists and some others largely discount culture because it cannot be neatly quantified. But neither can religion, ambition, humiliation, or vengeance, though these often have a far greater impact on the commitments and actions of peoples and governments than all the empirical data combined.

Exhibit A: Non-Communist Sinic Tigers

Fifty years ago, the major case studies for culture’s productive role in devising policies and institutions for national development, and then giving people the focus and drive to implement a reform program completely and successfully over the long term, might have been Max Weber’s industrious Protestants, Jews anywhere, or Chinese anywhere except in China.

In the past sixty years, another case-in-point has emerged—Asia's Sinic “Tigers,” which include Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. They have joined the developed world in a mere handful of decades. All non-communist Sinic countries made that leap while none of the communist Sinic countries (People’s Republic of China, Vietnam, and North Korea) did so, nor did any other country in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, or Latin America, with the exception of Israel.

The Tigers have only one characteristic in common that is not inherently available to peoples in other areas of the “developing” world. All of them have very long and deep links to the traditional culture of China, which represents the densest and most complex mix of progress-promoting and progress-resisting qualities of any culture in world history. The Tigers—like Overseas Chinese for centuries—have generally utilized the most progressive aspects of this culture while communist Sinic countries, until recent decades, have not.

One critically important characteristic of non-communist Sinic countries was the quality of leadership, often strongly influenced by two factors: the traditional Confucian teachings imbedded in Sinic thought that the ruler must serve the people and by the immediate concerns of leaders for their survival in the wake of communist seizures of power in the PRC, North Korea, and Vietnam.

The Confucian factor was particularly strong (but not unique) in Taiwan after 1949. As Kuo Tai-chun and Ramon Myers write in their new book Taiwan’s Economic Transformation, “the men who made the key decisions about Taiwan’s economic development . . . all felt the shame of having ‘lost’ the Chinese mainland. Along with this sense of humiliation, they shared a determination to expunge this disgrace.” This intense and profound cultural motivation is not characteristic of leaders in modern Africa, the Middle East, or Latin America.

Thus, the Tigers “got the economics right,” step-by-step created supportive institutions, and diligently implemented the chosen reforms. They generally focused on a strong dedication to good education as the expressway to success for individuals and nations, high goals pursued over the long term with unflagging diligence and a vigorous work ethic, frugality, and clearly defined goals governing the expenditure of funds and energy.

In varying degrees, the Tigers’ early governments were command economies, but national political leaders discussed long-term development plans with broad sectors of their societies and cultivated an increasingly vibrant private sector. In time and on purpose, this led to productive and reasonably balanced market economies and, in varying degrees, democratic political systems.

Just as the Arab Spring began, Yale Law School professor Amy Chua published her controversial memoir Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother on her strict raising of two daughters. They excelled, as have so many students of Sinic background who are in the United States. International testing in science, math, and other subjects finds that worldwide Sinic (along with Nordic) students are at “the top of the class.” The unstated subtext of Chua’s book was that “Tiger mothering” was one of the critical factors in the explosive modernization of Sinic Asia.

Consider, also, the case of South Korea. In 1960, South Korea’s per capita GDP was only half that of Mexico’s, slightly under Brazil’s and Syria’s, about the same as Egypt’s, and slightly better than Nicaragua’s. Today, its per capita GDP is twice Brazil’s, more than twice Mexico’s, seven times Egypt’s and Syria’s, and eighteen times Nicaragua’s. In 2011, the U.N. Human Development Index ranked South Korea as number 15, Mexico as 57, Brazil as 84, Egypt as 113, Syria as 119, and Nicaragua as 129.

The Communist Sinics

If developing countries want an example from Asia, they should look to the Tiger countries. But their successes are today taken for granted, while the PRC is universally regarded as the most explosively growing country in the world. To be sure, for more than three decades, the PRC’s GDP grew at an annual average of about ten percent. But China and the other communist Sinic countries are still very far from the developed world and, under current conditions, they may never get there.

Why? For many reasons. Even as the Tigers were reforming, the PRC defiantly tried to wipe out the progress-prone parts of China’s traditional culture. This continued in China until the late-1970s and in Vietnam for yet another decade. North Korea sets the world standard for intractable stagnation.

Even today, the CCP insists that it must play an unchallenged vanguard role in setting the economic and political course of the country; the state (as distinct from the private sector) must remain strong in some important areas, it believes. The state role is seemingly justified by the recent profligacy of so much of the developed world. But China’s sometimes inspired yet secretive—and indeed incestuous—system employs lofty and tradition-derived terminology even as it often rewards patronage-based mediocrity and limits the thought and actions of potentially creative people who do not wear the authorized dark suits of the mind.

A Universal Progress Culture

As noted above, Sinic cultural values have long been similar to those found in Weber’s protestant Europe and among the Jews, Basques, and other groups. Chua insists that “tigering” can be practiced by individuals or groups of any ethnicity, age, sex, or historical period. Indeed, jousting with TV comic Stephen Colbert, the tiger mother noted that her approach reflects the most basic of traditional American values: “hard work, don’t blame others, and don’t give up.” These values have always been or became much less influential or absent in non-Sinic Asian, African, Arab, and Latin American countries.

In a forthcoming book entitled Jews, Confucians, and Protestants, the cultural historian Lawrence Harrison calls the generalized version of Sinic values a “Universal Progress Culture” for it transcends time, place, and racial/ethnic grouping. He also argues that while culture is strongly rooted into a society, it can change. A progress-prone cultural orientation can, in time, decline if people become lazy or indifferent while a progress-resistant culture can become progressive if people want it enough to make the necessary long-term effort.

Chilean President Sebastián Piñera has vowed to make Chile the first fully-developed country in the world since the Tigers. Others who do not want such a future or do not have the stamina to transform their country so completely may choose a different path forward. The bottom line is that cultures have enormous consequences and all efforts to reform a developing country must be conceived, executed, and measured with that reality in mind.