- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- US Labor Market

- Energy & Environment

- US

- Economic

- Contemporary

- World

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- History

The year started out poorly for Riyadh. In January, the Lebanese government it had backed fell because of pressure from Hezbollah. An ally, Tunisian President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, was thrown out of office by a popular rebellion; soon after, kindred spirit Hosni Mubarak, president of Egypt and a close partner against Iranian influence, made his ignominious departure. Then came eruptions in Morocco, Jordan, Libya, Yemen, Oman, Kuwait, and—most ominously for Riyadh—Bahrain.

Bahrain’s ruling Al Khalifa family, Sunnis like the Saudi royals, were rattled by the mass demonstrations of the Shiite majority. The Saudis could not help but take notice in light of their own restive Shiite population in the oil-rich Eastern Province.

A few, small demonstrations took place in Saudi Arabia and petitions (three petitions, at latest count) were circulated. A “day of rage” was called for March 11. But although the petitions demanded more participation in decision-making, better governance, and an end to corruption, they did not call for revolution. The slogan heard in Tahrir Square, “The people demand an end to the regime,” has yet to be heard in the streets of Riyadh and Jeddah.

DEALING WITH DISSENT AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Saudi Arabia has gone through tremendous social change since it was established in 1932. The discovery of oil, economic growth, and a booming population all put strain on a very traditional country. Other political systems might have cracked under the strain, but the Al Saud have put into place a system that has so far met these challenges. They seem well positioned to weather the current one as well.

The founding fathers harnessed the tribalistic nature of Saudi society to the enterprise of state formation. Tribes were used as a military force, and tribal values such as kinship played a key role in the state’s development. The sons and grandsons of founder Ibn Saud hold all-important cabinet posts and govern the most important provinces. Using classic coup-proofing methods, King Faisal divided military forces between family factions and drew internal security forces from the most loyal tribes of the Najdi heartland.

Crucially, the Wahhabi religious establishment, so important for the ruling family’s legitimacy, was co-opted to support slow, careful modernization in the form of economic and social development, while conservative values were protected. King Faisal was the master of this approach. He instituted women’s education, television broadcasting, and the expansion of a government bureaucracy many times over to handle the new oil wealth and provide jobs for a growing population. He challenged the conservative Wahhabi religious establishment and won.

The Al Saud family struck an alliance with American presidents in which the United States promised to protect oil installations in exchange for access by U.S. companies and the free flow of oil.

As oil income became significant, the Saudi royals used a distributive model to develop the country. Huge infrastructure projects, educational institutions, hospitals, and an enlarged military benefited many. Housing projects for previously nomadic or seminomadic Bedouin brought modern conveniences, along with closer control by the central government. Huge subsidies for fuel and other goods, along with a stock market that the government occasionally propped up, saw to it that the wealth was distributed to a large swath of people.

But as the population grew, it became harder to distribute the wealth. Nor was it distributed equally. People in the Hijaz complained that Najdis were favored, and the Shiites of the Eastern Province suffered both economic and religious discrimination.

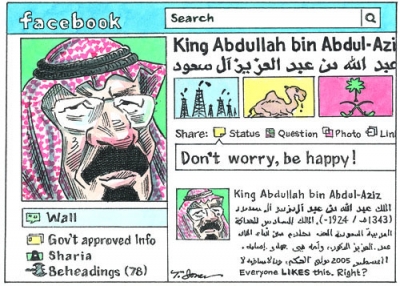

Corruption and nepotism among the royal family became a common complaint. While residents born during the early years were quite aware of the tremendous progress the Al Saud had brought the country through oil wealth, younger generations know only the Al Saud, and are less appreciative. Through the technology so readily available to them, they can examine life in other places and share it with their friends. The government can no longer monopolize information.

Saudi Arabia has always had political dissent. The 1950s and 1960s saw the influence of Nasserism, communism, socialism, and Baathism. The religious establishment helped combat such challenges from the left. Where violence occurred, such as among the disenfranchised Shiites in the Eastern Province in the 1950s and in 1979–80, the government did not hesitate to send in the Saudi national guard to restore order with a heavy hand.

Since the 1990s, two waves of political challenges have swept the country, each resulting in some reforms. The first, catalyzed by opposition to the presence of U.S. troops in the country during the 1990–91 Gulf War, resulted in the announcement of a consultative council appointed by the Al Saud. The second wave came after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States by a mostly Saudi Al-Qaeda cell. Reformers took advantage of those events to press their demands. The consultative council was expanded, municipal elections (for half the seats of the municipal councils—the rest would remain royal appointees) were announced, and national dialogues were held. Many called this period the “Riyadh spring of 2003.” It ended with a series of Al-Qaeda terrorist attacks in May and the arrest of several reformers in March 2004.

The Al-Qaeda insurrection allowed the government to crack down on the reformists. But the ascension of King Abdullah to the throne in 2005 gave reformers fresh hope, as did the municipal elections finally held that year. The Al-Qaeda insurrection was essentially suppressed by 2007, although sporadic attacks still occur. Its suppression has contributed to the reopening of political space for the resurgence of the reformist activity we see today.

RIYADH VERSUS THE “ARAB SPRING”

The revolt in Tunisia caught the Saudi royal family at an awkward moment. King Abdullah, eighty-seven, had been out of the country since November, when he flew to the United States for an operation. The crown prince, Sultan, nearly as old and also known to be ill, had flown back from Morocco to stand in for Abdullah, but day-to-day matters were actually being run by Prince Nayif, the minister of the interior and potential crown prince to Sultan, and widely considered to be quite conservative and close to the religious establishment. Conservatives may have been satisfied with this line of succession, but it did not portend well for younger reformers influenced by the revolts sweeping the Arab world.

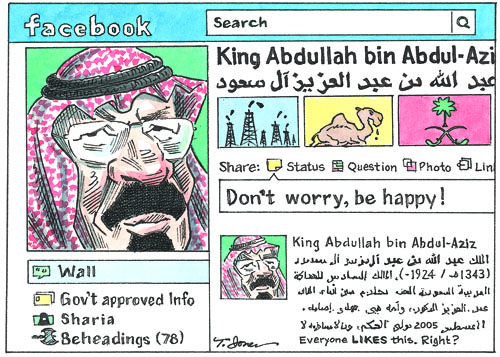

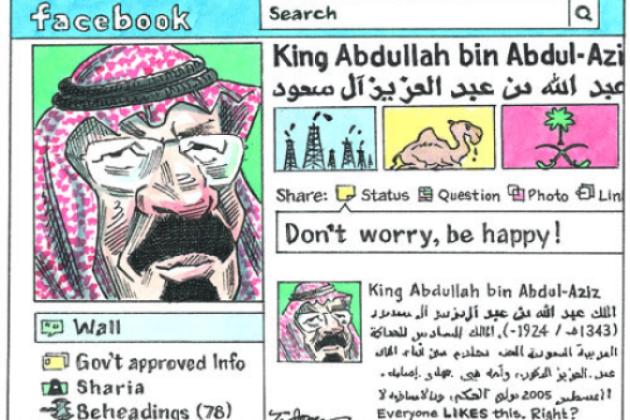

The Saudi government censors the Internet, but not completely, and the Qatar-based news station Al-Jazeera is beamed into every Saudi home. Just as Tunisia’s “Jasmine Revolution” was gaining steam in late December and early January, the government announced that all blogs and news sites would now need to apply for a license. The new regulations had been discussed for a while, but the royal family saw fit to announce them exactly when social media were gaining prominence as a tool of the Tunisian revolt.

Unequal wealth distribution, corruption, inflation, unemployment, and lack of freedom have bothered Saudis for many years. Demonstrations are rare, and illegal, but the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association requested to stage a sit-in protest in late December. Permission was denied, and the group publicly demanded the firing and prosecution of Prince Nayif in early January. Unemployed teachers had already demonstrated in August, and did so again in January. Then several Saudi women began a Facebook campaign to allow women to vote for municipal councils. Clearly, grievances were becoming more public.

TRICKLE OF PROTESTS, FLOOD OF MONEY

While bloggers were discussing events in Tunisia and then in Egypt, two events put a damper on possible contagion from those countries. First, top leaders condemned the uprisings. The widely respected king, from his sickbed in Morocco, came out strongly against the demonstrations in Egypt and in support of Mubarak. Demonstrators were inciting fitna, or discord, he charged, and therefore going against the traditional Islamic order. The general mufti, Sheikh Abdul Aziz bin Abdullah al-Sheikh, echoed the king, accusing the demonstrators of sowing discord between the people and the rulers.

The main event occupying Saudis in late January was the disastrous flooding in Jeddah, which killed at least ten people. On January 28, police arrested dozens of protesters in Jeddah who were outraged by the floods. People were making connections between their own government’s lack of accountability and what was going on in Tahrir Square.

Attention moved back to the local implications of what was going on in Egypt as events became more dramatic there in February. Taking their cue from Tahrir’s main slogan, a Facebook page was opened under the title “The people demand reform of the regime,” stopping just short of Tahrir’s call for toppling the regime. The group called for an elected parliament, political freedoms, the right to organize political parties, women’s rights, and a constitutional monarchy.

On February 10, Islamists announced the formation of the Islamic Umma Party (IUP). Most of the founders seemed to be clerics not connected to the religious establishment. They sent a letter notifying the royal court that the party had been established. Speaking in an Islamic idiom, the party demanded political freedoms, elections to the legislature, and the right to engage in advocacy of peaceful political reform. Political parties are illegal in Saudi Arabia. The regime therefore did not take kindly to the establishment of the IUP, arresting several leaders.

But the regime tried to show its willingness to lend an ear. Prince Khalid al-Faisal, a contender for the throne and governor of Mecca Province, where Jeddah is, invited five media personalities to a televised briefing after the floods. Among them was Fuad al-Farhan, a blogger who had once been arrested and banned from traveling. Khalid asked Farhan to send his regards to the “young people on Twitter.” In another move, a Facebook page was apparently set up by Khalid bin Abd al-Aziz al-Tuwayjri, the chief of the royal court, on which people were invited to fax in their complaints—something they could already do.

While still in Morocco, the king responded to protests in a time-tested manner: he offered government aid. The government said the king would write off $156 million in housing loans. The governor of Riyadh Province, Prince Salman, announced the expansion of a food bank named for the king. But the biggest announcement was timed for the king’s return February 23. With oil prices at over $100 a barrel filling his coffers, the king opened the Privy Purse. Saudi Arabia would introduce nineteen new measures, at an estimated cost of over $36 billion, aimed primarily at unemployed youth, to help them with unemployment benefits and affordable housing. Huge sums were also allocated for higher-income students studying abroad at their own expense. Grants were to be made for household expenses and renovations (the latter a gesture to those with homes damaged by the Jeddah floods); a temporary 15 percent salary increase for state employees was made permanent.

In the meantime, events in the kingdom and the region as a whole began a slide in the Saudi stock market, where millions of Saudis gambled their fortunes. But, true to form, it was reported that government funds had bought stock in all sectors, causing a recovery. Once again, the state had come to the financial rescue of its citizens.

“DAY OF RAGE”? NOT YET

While the Al Saud timed the aid package for the king’s return and mass welcome by a grateful population, Saudi dissidents riding the wave of protests in the Arab world were preparing another kind of welcome. This was in the form of a “Letter from Saudi Youth” calling for a national dialogue conference with binding recommendations and massive governmental reforms that would allow young people a more active role in decision-making. A few days later, another petition appeared with a bit more gravitas. Signed initially by more than one hundred leading liberal Saudi academics, businessmen, and activists, the “Declaration of National Reform” called for the people to be the source of legitimacy, for the country to move in the direction of a constitutional monarchy, and for oversight of government spending to ensure equitable distribution of wealth. Prominent Shiite activists signed as well.

Members of Saudi Arabia’s Shiite population, who make up 10–15 percent of citizens and are concentrated in the oil-rich Eastern Province, just across the King Fahd Causeway from Shiite-majority Bahrain, have often demonstrated, including violently, and have been put down with equal violence. Throughout Saudi history, they have protested discrimination and persecution by their Al Saud rulers, who draw their inspiration from the viscerally anti-Shiite Wahhabi trend of Sunni Islam. Many Saudis distrust the Shiites, believing them to be agents of Iranian influence.

It was no surprise, then, that the first serious signs of public unrest would come from the Shiites. After protests by fellow Shiites in Bahrain in mid-February, a small but vocal demonstration was held in Awwamiya to protest the detention of Saudi Shiite activists. The government responded by releasing the activists, but this only drew another demonstration in Qatif the next week calling for more prisoners to be released. Around February 27, the authorities arrested a Shiite cleric for calling for a constitutional monarchy. Yet true to its carrot-and-stick approach, at the same time the regime allowed the reopening of several Shiite mosques in Al-Khobar. Demonstrators could be heard chanting “no violence, no violence” (silmiyya, silmiyya), like the protesters in Bahrain and Egypt.

Riyadh was understandably anxious—even desperate—to make sure that the Bahraini royal family survived its most serious challenge to date. On February 17 the Saudis called a meeting in Manama of the Gulf Cooperation Council foreign ministers, who pledged full political, economic, security, and defense support for the Al Khalifa of Bahrain. Together with Washington, Riyadh tried to move the Bahrainis towards talks and compromise.

The message was clear: “The kingdom of Saudi Arabia stands with all its capabilities behind the state and the brotherly people of Bahrain,” read an official statement. On March 14, around one thousand troops from the Gulf Cooperation Council “Peninsula Shield” forces crossed over into Bahrain to protect the Al Khalifa.

The calls for a “Day of Rage” on March 11 after Friday prayers seem to have emerged from the Shiite activists, influenced by similar calls in Bahrain and Egypt. Several Facebook pages were established for the event, but did not seem to gather more than a few thousand “likes.” The low number could be attributed to Saudi blocking, but just as easily could be a result of most Saudis not being willing to cross the line.

The regime made it clear that no demonstrations would be tolerated. It mobilized close to ten thousand troops to be ready for protests in the Eastern Province, and went through another round of arrests and releases in the region. Surely in the back of the rulers’ minds were the violent Iranian-inspired demonstrations in 1979–80 known to locals as the “Intifada of the Eastern Province.” The Council of Senior Scholars, representing the religious establishment, published a paean to the regime as a rock of stability and unity based on Islamic principles, hinting at outside influences that had caused discord and crisis and warning against deviant (unnamed) intellectual and partisan trends. As before, it stated that the proper Islamic way to redress grievances was through (silently offered) advice, not proclamations and demonstrations. All mosque preachers and imams received orders from the Ministry of Islamic Affairs to read out a warning against demonstrations. The regime worked its tribal and regional ties.

The regime hoped that it would not have to use violence, opening itself up to the kind of condemnation heaped upon Ben Ali and Mubarak. But it seemed clear that it would not hesitate to do so.

To many young people, the commands to be deferential must have sounded anachronistic, out of touch with the Internet age. Yet the massing of troops and police and the warnings from the highest authorities had their effect. The Day of Rage did not materialize. Worshippers left the mosques peacefully.

U.S.-SAUDI RELATIONS: IT’S COMPLICATED

As the United States searched for a clear, meaningful response to the events in Egypt, Bahrain, and eventually Saudi Arabia itself, the Al Saud were puzzled and eventually angered. In the Saudi view, Washington had treated Mubarak shabbily, and reports said that King Abdullah had upbraided President Obama about his treatment of a U.S. ally. The head of Al-Arabiyya satellite channel, ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Rashid, wrote that Obama was encouraging Iran and meddling in Egyptian affairs; the Egyptians in the street would not requite America’s love. The veteran foreign minister, Saud al-Faisal, spoke sharply of “interference in the internal affairs of Egypt by some countries.”

Obama sent the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, to calm the Saudis and others in the region. But on March 7, State Department spokesman P. J. Crowley said Washington supported the right of peaceful assembly, “including [in] Saudi Arabia.” Saud al-Faisal was livid. The Saudis supported dialogue, he said. “Change will come through the citizens of this kingdom and not through foreign fingers; we don’t need them. We will cut any finger that crosses into the kingdom.” The last phrase may have referred to Iran as well. Relations appeared to be under strain. An unnamed U.S. official sought to calm the Saudis in an interview, stressing that relations were firm and based on principles and mutual interests. Still, it was clear that the United States now believed that democracy in Egypt and reform in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia were the keys to stability.

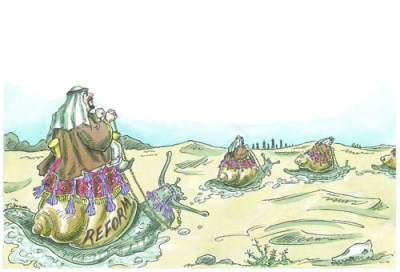

The Al Saud will probably have to give, somewhere. But it is sure to be a tough sell. Despite the growing influence of the young, Saudi Arabia remains a very traditional society. Too much reform, too fast, and the ruling family will see its conservative base erode. King Abdullah will have to continue the balancing act.

The Al Saud could take several steps without undermining the current order. They could allow long-delayed municipal elections, last held in 2005. They could consider letting women participate. Women could also be allowed to drive, a symbol of modernity that many Saudis want. (Prince al-Walid bin Talal, who proposed this concrete step in an interview, said it would allow the kingdom to send home more than 750,000 foreign drivers.) The government could boost employment. It could allow elections for the appointed Consultative Council, as demanded by the reformers, initially vetting the candidates as Iran does but promising entirely free elections in four years.

In the meantime, the steps taken to defuse the current crisis seem to be working. The Sunni majority is not culturally accustomed to mass demonstrations; the violence in Libya reminded many Saudis of the consequences of chaos. Tribal and family connections remain very strong and militate against organized opposition. The young generation still bears watching, though. Connections made online might someday compete with traditional social ties. But tribes have websites, too.

Columnist Maureen Dowd once remarked that observing change in Saudi Arabia is like watching a snail on Ambien. The Saudis will have to consider moving faster. No doubt, however, they are painfully aware of what Samuel Huntington once termed the king’s dilemma, that “limited reforms introduced from the top often increase rather than decrease bottom-up demand for more radical change.” The shah of Iran’s “white revolution” was a case in point, as was Gorbachev’s perestroika. Saudis are therefore likely to prefer that reform arrive at a snail’s pace.