- History

- Military

The sage, albeit overly quoted, wisdom of the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu still applies in modern warfare: “Know your enemy and know yourself, find naught in fear for 100 battles. Know yourself but not your enemy, find level of loss and victory. Know thy enemy but not yourself, wallow in defeat every time.”

The agony of defeat inflicted by the Vietnam War to America belongs to a separate category corollary to Sun Tzu’s pronouncement. It was caused by neither knowing the enemy sufficiently, nor ourselves.

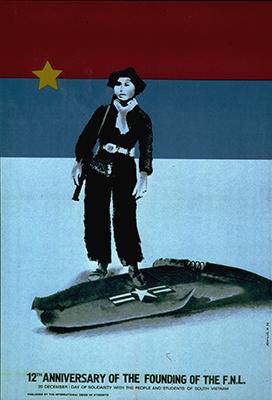

While the war in Vietnam was regarded by the bulk of the defense and intelligence establishment as a proxy war between the Communist bloc and the free world, for many Americans who suffered from a severe case of “poverty of ideology,” the enemies were the rice paddy guerrillas. In their view, these guerrillas were the semi-primitive Vietnamese peasant insurgents whose anti-French, thus anti-colonial, nationalism was led by the charismatic Uncle Ho, who befriended the Soviet Union and communist China to gain material support in order to fight France’s successor, the United States. They believed that Ho’s motivation, however, was not necessarily to forge an ideological common ground and fulfill Moscow, Beijing, and Hanoi’s solemn commitment to proletarian internationalism for the humiliation, weakening, and eventual overthrow of the Western bourgeoisie headed by the United States.

Thus, throughout most of the Vietnam war, a fundamental question for Americans remained unanswered: are we fighting against Vietnamese nationalists yearning for independence, or are we fighting international communists in a proxy war with the Soviet Union, China, and North Vietnam? Without an answer, there was no way to gain a national consensus on our conduct of the war in Vietnam.

Americans also began to have self-doubt during the Vietnam War years when a cultural revolution on America’s campuses, TV screens, newsrooms, and living rooms turned violently self-critical and in many cases brimmed with self-loathing against the society and the nation’s founding principles in general, and the war in Vietnam in particular.

The failure to comprehend sufficiently the deeply ideological nature of the Vietnam War, and the gradual loss of self-confidence in America’s inherent goodness, contributed greatly to the United States’ defeat in Vietnam.

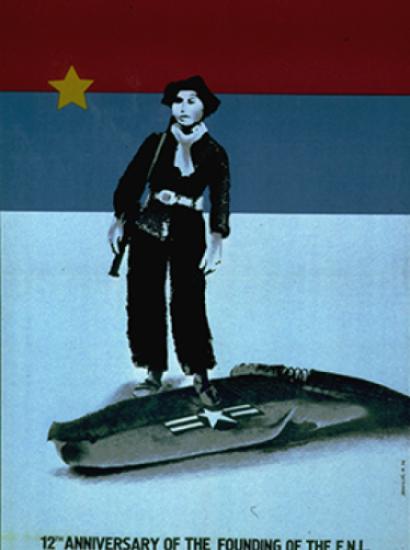

The dual failures critically affected America’s war strategies and tactical operations. We greatly underestimated our enemies and regarded them as mere Vietnamese peasant nationalists in straw hats who were only good at scattered guerilla warfare. We equated their limited supply of sophisticated military hardware with limited lethality and underestimated their capability of waging Soviet-styled, well-coordinated, mechanized modern warfare. By the time Americans realized the falsity of this thinking in the February 1968 Tet Offensive, it was too late as the tidal waves of the anti-war movement would soon cripple the American political and military leadership’s ability to adjust and win the war on the proper footing. Eventually, America would beg Moscow and Beijing to reduce their support for Hanoi so that we could settle for an honorable exit which never really happened as Moscow and Beijing only paid lip service to President Nixon’s entreaties, but backed Hanoi with more tanks, missiles, and fighter jets that eventually “liberated” South Vietnam in 1975.

The communists also had their own self-awareness problems coming out of the Vietnam War. Moscow and Beijing had been competing for the leadership of the worldwide communist movement and both used the war in Vietnam as a proving ground to demonstrate that leadership capability. Yet in the course of this brotherly competition, Vietnam went over to Moscow, thus alienating Beijing, which considered Hanoi a perfidious ingrate. In the aftermath of the American defeat in Vietnam, the Moscow-backed Hanoi overthrew the Beijing-backed Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. For this, China punished Vietnam by launching a full-scale invasion in February 1979. Yet ten years later, the Soviet empire began to collapse and the Berlin Wall came down in November of that year.

Today’s China still remains communist and Vietnam is also ruled by a communist dictatorship and a Politburo. Even though a communist internationale is nowhere in sight, and their defeat is not as thorough, they at least knew their enemy, if not completely themselves.