- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Monetary Policy

- Economic

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- History

Hoover senior fellow John B. Taylor spoke in April at the twenty-fifth anniversary meeting of the Macroeconomics Annual conference series, sponsored by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Here is what he said:

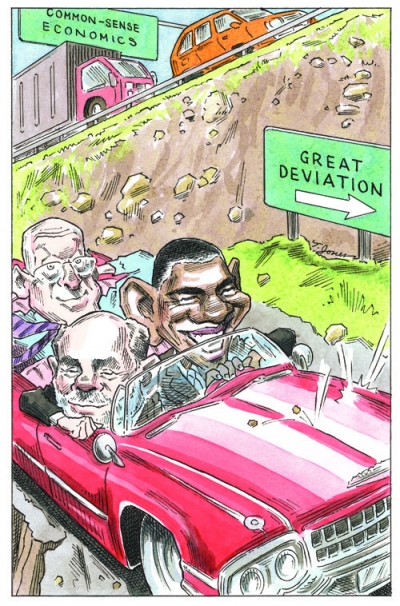

Let me begin with an explanation of the title of my talk, “Macroeconomics Lessons from the Great Deviation.” I know economists use the word “great” too much, but I think it is quite fitting here. We all know what the Great Moderation was and we have debated what caused it. Many have argued that good policy, especially good monetary policy, played a big role. And we all know what the Great Recession was and that it marked the end of the Great Moderation. You may not have heard much about the Great Deviation. I define it as the recent period during which macroeconomic policy became more interventionist, less rules-based, and less predictable. It is a period during which policy deviated from the practice of at least the previous two decades, and from the recommendations of most macroeconomic theory and models. My general theme is that the Great Deviation killed the Great Moderation, gave birth to the Great Recession, and left a troublesome legacy for the future.

The policy actions and interventions that I would put under the rubric of the Great Deviation include the following:

- Deviation from the monetary policy of the Great Moderation, 2003–5

- Term auction facility (TAF), created by Federal Reserve, 2007

- U.S. discretionary fiscal stimulus, 2008

- On-again, off-again interventions of financial firms by the Fed, 2008

- Money-market mutual-fund liquidity facility, 2008

- Commercial-paper funding facility, 2008

- U.S. discretionary fiscal stimulus, 2009

- G-20 fiscal stimulus agreement, 2009

- Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) purchase program of the Fed, 2009–10

- Trillion-dollar European rescue package, 2010

- The European Central Bank (ECB) joining the rescue package by buying distressed debt, 2010

- The Fed joining the rescue package by making swap loans, 2010

That’s a dozen already, and one could add more, including interventions by the federal government to encourage Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to purchase high-risk mortgages, and decisions by U.S. financial regulatory agencies to let banks deviate from rules-based regulations by allowing risky off-balance-sheet activity or by not monitoring the risk of complex asset-backed securities on the balance sheets. And there are also the many deviations from the rules-based Stability and Growth Pact in Europe, which are the cause of the crisis Europe is facing now. But let me focus on these dozen.

First on the list is the decision by the Federal Reserve during 2003–5 to hold its target interest rate below the level implied by monetary principles that had been followed for the previous twenty years. One can characterize this decision as a deviation from a policy rule, such as the Taylor rule, and in that sense it is a deviation from a more rules-based policy. Without this deviation, interest rates would not have reached such a low level and they would have returned much sooner to the neutral level that they eventually reached. The deviation was larger than any other during the Great Moderation—on the order of magnitude seen in the unstable decade before the Great Moderation. One does not need to rely on the Taylor rule to conclude that from the perspective of many of the standard objective functions that monetary policy might seek to optimize, rates were held too low for too long. The real interest rate was negative for a very long period, similar to what happened in the 1970s. The intervention was an intentional departure from a policy approach that was followed in the decades before. The Fed’s statements that interest rates would be low for a “prolonged period” and that interest rates would rise at a “measured pace” is evidence of these intentions.

The low interest rates added fuel to the housing boom, which in turn led to risk taking in housing finance and eventually a sharp increase in delinquencies, foreclosures, and the deterioration of the balance sheets of many financial institutions as toxic assets grew rapidly. To test the connection between the low interest rates and the housing boom I built a simple model relating the federal funds rate to housing construction. My research showed that a higher federal funds rate would have avoided much of the boom and bust.

The next intervention on the list is the Fed’s term auction facility (TAF) created in December 2007. The purpose of the TAF was to reduce tensions in the interbank market, which had risen sharply in August 2007.

The TAF provided a way for banks to get loans from the Fed without using the discount window. After this facility was created, tensions in the interbank market—as measured by the spreads between LIBOR at various maturities and the overnight index swap (OIS)—abated for a while, but soon shot up again. My view, based on research with John C. Williams, is that this new facility had little or no effect on these interest-rate spreads. Measures of counterparty risk in the banking sector, such as the spread between secured and unsecured interbank loans, explain money-market spreads very well. In my view, this policy intervention prolonged the crisis because it did not address the deterioration of the balance sheets at banks and other financial institutions. We now know the banks were holding many toxic assets, but the problem was diagnosed as a liquidity problem.

The 2008 discretionary countercyclical fiscal-policy action—the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008—is next on the list. This action was also a deviation from the type of policy that was used in the Great Moderation, a period in which there was a near consensus among economists that such discretionary policies were not effective and could be counterproductive. As part of this stimulus, which was passed in February 2008, checks were sent to people on a one-time basis and aggregate disposable personal income jumped dramatically though temporarily. The objective was to jump-start consumption demand and thereby the economy. However, aggregate personal consumption expenditures did not increase by much around the time of the stimulus payments. This is what the permanent-income theory, the life-cycle theory, or modern new Keynesian models predict from such a temporary lump-sum payment.

The most unusual and significant set of interventions were the on-again, off-again rescues of financial firms and their creditors. The interventions started when the Fed opened its balance sheet to rescue the creditors of Bear Stearns in March 2008 and then made loans available to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Fed’s interventions were then turned off for Lehman, turned on again for AIG, and then turned off again when the Troubled Assets Relief Program was proposed. These interventions clearly did not prevent the panic that began in September 2008, and in my view were a likely cause of the panic, or at least made it worse. Could the unpredictable nature of these interventions have been avoided? If the Federal Reserve and the Treasury had laid out clearly the reasons behind the Bear Stearns intervention as well as the intentions of policy going forward, then people would have had some sense of what was to come. But no such description was provided. Uncertainty was heightened and probably reached a peak when the TARP was rolled out. Panic ensued and quickly spread around the world as stock market indices went down in tandem with the 30 percent drop in the S&P 500.

The panic halted when uncertainty about the TARP was removed on October 13, 2008. The original purpose of the TARP was to buy up toxic assets on banks’ balance sheets, but there was criticism and confusion about how that would work. After the TARP was changed to inject equity into the banks rather than to buy toxic assets, uncertainty was reduced and conditions began to improve, as measured by LIBOR-OIS spread and other indicators such as the S&P 500. Market conditions then improved in other countries.

Other policy interventions were taken during the panic in late September and October 2008. The Fed’s programs to assist money-market mutual funds and the commercial-paper market were helpful in rebuilding confidence. To be sure, the panic period is complex to analyze empirically because so much was going on at the same time. In addition to the Fed’s actions, we had the FDIC guarantee of bank debt and the clarification that the TARP would be used for equity injections.

After the worst of the panic was over, there were more interventions. Another discretionary fiscal stimulus—the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009—was passed in February 2009. The amount paid in checks was smaller and more drawn out than the 2008 stimulus, but the impact was about the same: no noticeable effect on consumption. In addition, my analysis of the government-spending part of the stimulus suggests that it had little to do with the turnaround in economic activity.

At the G-20 leaders’ summit in the spring of 2009, other countries agreed with the U.S. approach and passed their own discretionary fiscal-stimulus packages—a contagion of deviations from rules-based predictable policies around the world. (This is number eight on my list, but it could be numbers eight to twenty-six.) We are still learning about the impact of these packages, and a huge amount of empirical work is needed to determine their impact.

The Fed introduced other interventions in the period after the panic, most significantly the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) purchase program, which turned out to be $1.25 trillion in size. My view, based on empirical research with Johannes Stroebel, is that this program had only a small effect on mortgage rates once prepayment risk and default risk are controlled for.

Many of these policies have helped create legacies of debt and monetary overhang. Moreover, the central bank interventions raise questions about central bank independence; the interventions are not monetary policy as conventionally defined but rather fiscal policy or credit allocation policy. Unwinding the programs creates uncertainty, but there is a risk of inflation if they are not unwound. The fiscal interventions have resulted in higher debt levels, and they have redirected policy attention away from issues of long-term fiscal consolidation.

Nowhere is there more evidence of this legacy of debt than in Europe, where the debt problems of Greece, Portugal, and Spain worsened significantly after the crisis. Indeed, the earlier interventions have led to more interventions: the 750 billion euro rescue package by European governments and the IMF, the agreement by the European Central Bank to buy distressed government debt, and the agreement by the Fed to provide dollar swap loans to the ECB to relieve pressure in the interbank market. I have added these echo interventions to the list. It is still too early to determine their impact, but the early movements in the interbank and exchange markets were not favorable.

OTHER VIEWS

Others have different views of the Great Deviation. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, for example, argues that I use the wrong Taylor rule to measure the deviation from rule-based policies. He shows that the low interest rates in 2003–5 were not a deviation if you use a modified policy rule with forecasts of inflation rather than actual inflation. But the Fed’s forecasts of inflation were too low in this period, which suggests that such a modified rule is not a very good one.

Some would say that the Great Deviation was needed. For example, the financial panic in the fall of 2008 and the Great Recession were so severe that policymakers had to take large, unprecedented discretionary actions. But the first four action items on my list were taken before the panic of fall 2008 and before the recession that started in late 2007 turned into the global Great Recession.

Others might say that my research ignores mistakes in the private sector. Of course there were market problems of various sorts. Mortgages were originated without sufficient documentation or with overly optimistic underwriting assumptions, and then sold off in complex derivative securities, which credit rating agencies rated too highly. Individuals and institutions took highly risky positions through either a lack of diversification or excessive leverage ratios. But such mistakes do not normally become systemic, and in my view, the government actions tended to convert nonsystemic mistakes into systemic risks. The low interest rates led to rapidly rising housing prices with very low delinquency and foreclosure rates, which confused both underwriters and the rating agencies or made it easier for them to hide the mistakes. The failure to adequately regulate those entities that were supposed to be, and thought to be, regulated certainly encouraged the excesses. I have already mentioned how regulators allowed risky activities at banks. Regulatory gaps and overlapping responsibilities added to the problem.

Still others might say that things would have been worse without the Great Deviation, that we would have had Great Depression 2.0 without the Great Deviation. I see no hard evidence for this claim. If I could pick and choose among the policies on my list, I would select the Fed’s actions for the commercial-paper market and money-market funds, but those actions would not have been needed were it not for the preceding items on the list.

KEEPING MODELS THAT WORK

What are the implications for the field of macroeconomics of the Great Deviation and what ensued in the global economy? The recent crisis gives no reason to abandon the core empirical “rational expectations/sticky price” model developed over the past thirty years. Whether you call this type of model “dynamic stochastic general equilibrium” or “new Keynesian” or “new neoclassical macroeconomics,” it is the type of model from which modern monetary policy rules and recommendations were derived. Along with rational expectations came reasons for predictable, rule-like policies. Along with the sticky prices came specific monetary rules that dealt with the dynamics implied by those rigidities, as fitted to actual macro data. This is the type of model where robustness of policy rules could be checked, as it was in the NBER’s Monetary Policy Rules [edited by John B. Taylor, University of Chicago Press, 1999].

These models did not fail in their recommendations for rules-based monetary and fiscal policies. I have to disagree with Narayana Kocherlakota when he says that “macroeconomists let policymakers down . . . because they did not provide policymakers with rules to avoid the circumstances that led to the global financial meltdown.” The rules were provided. Policy makers took a different, more discretionary approach.

It is easy to criticize the rational expectations/sticky price models by saying that they do not admit enough rigidities, or have only one interest rate, or do not have money in them. But we should not confuse useful simplified versions of models, which frequently boil down to only three equations, with more complex and detailed models used for policy. For practical policy work, those simplifying assumptions are relaxed. Of course, macroeconomists should try to improve their models however they can to make them more useful for policy makers. Many have been working to improve our understanding of the credit channel, for instance. My findings imply that we need to do more work on “political macroeconomics.” In particular, we need to explain and understand why policy makers moved in such an interventionist direction despite the research that stressed predictable, rule-like monetary and fiscal policy. Once we understand that, practical solutions should follow.

One possible explanation is that policy makers genuinely doubted the practical relevance of the research on policy rules. In this regard I am reminded of the 1992 Macroeconomics Annual conference. That year I presented the paper that contained what would come to be called the Taylor rule. At the conference I commented on a paper by Ben Bernanke and Rick Mishkin; they had raised doubts about the use of rules for policy instruments and made a case for a considerable amount of discretion in monetary policy making. “Monetary policy rules do not allow the monetary authorities to respond to unforeseen circumstances,” they said. I dissented from that view in my comments, referring to research on policy rules in which the instruments of policy do adjust to contingencies.

Another explanation for the deviation is that policy makers, in a practical setting, sometimes try to do more than the underlying economics suggest is possible. Let me close with a statement that Milton Friedman made during congressional testimony more than fifty years ago. I draw this quote from the famous debate between Friedman and Walter Heller in which Friedman refers to his 1958 testimony before the Joint Economic Committee. According to Friedman,