This essay is based on the working paper “Jim Crow and Black Economic Progress After Slavery” by Lukas Althoff and Hugo Reichardt.

Racial inequality has been one of the most stubborn challenges confronting American society. Black Americans continue to face significant disadvantages in economic opportunity and prosperity. For instance, the average wealth of a Black person today is less than one-fifth of that of a White person. Large gaps also prevail in education, income, and numerous other socioeconomic indicators, where Black Americans consistently lag behind their White counterparts.

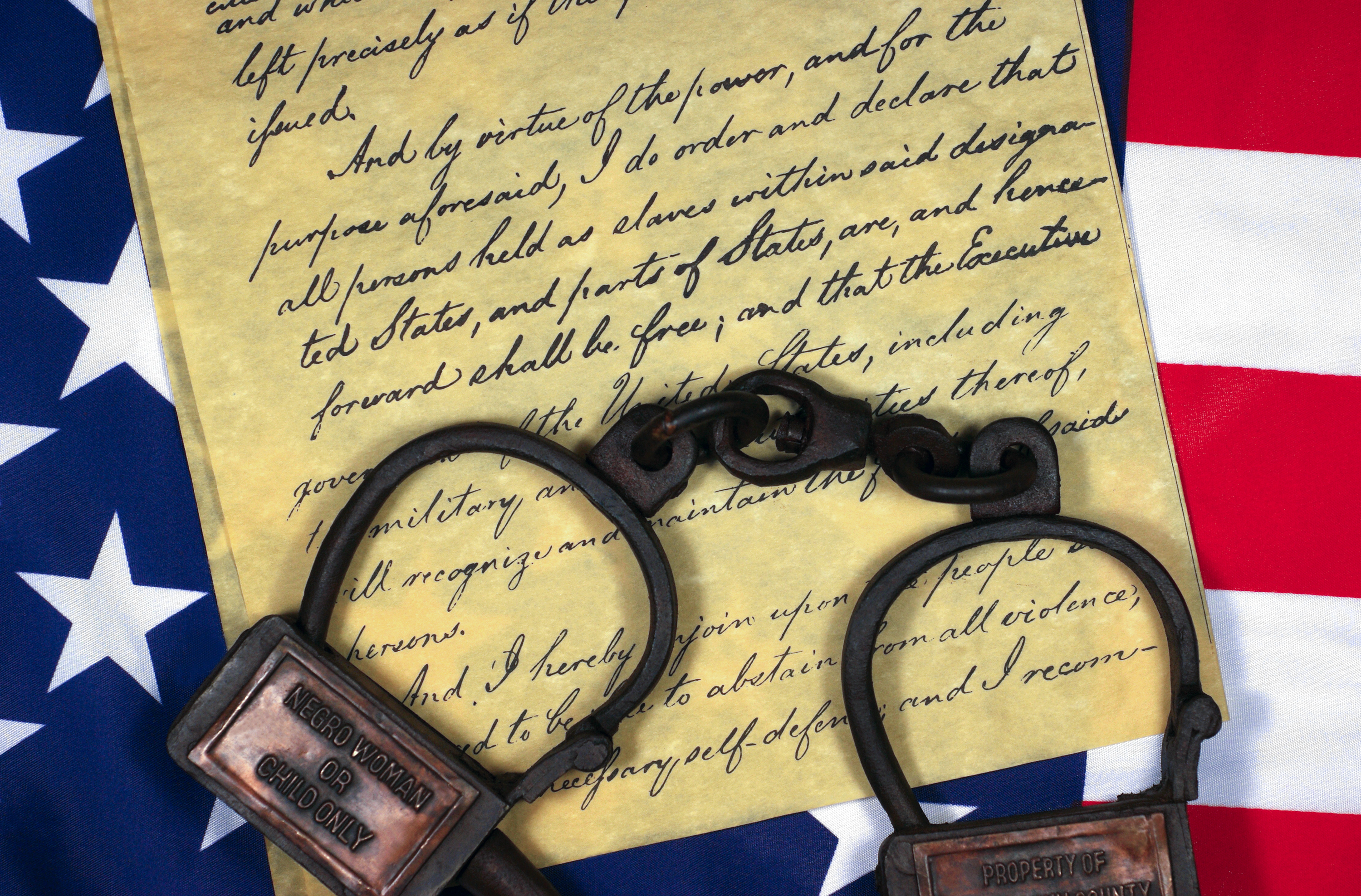

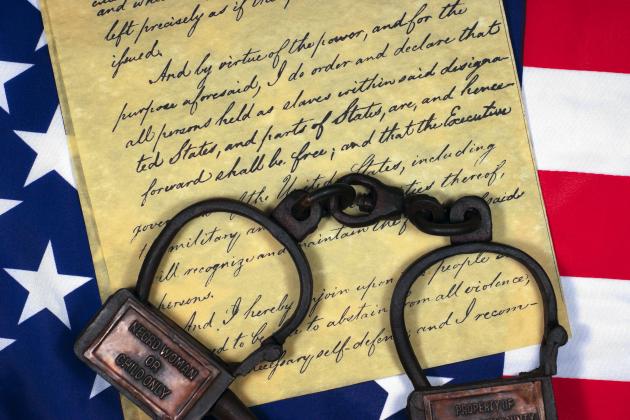

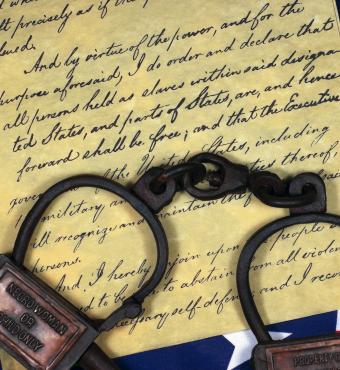

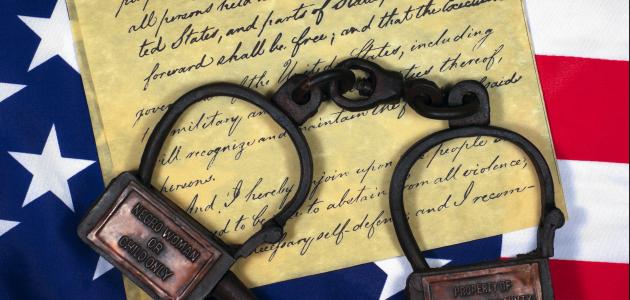

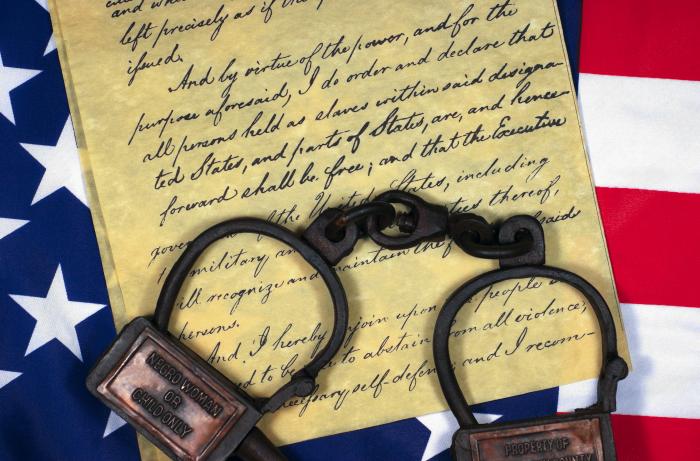

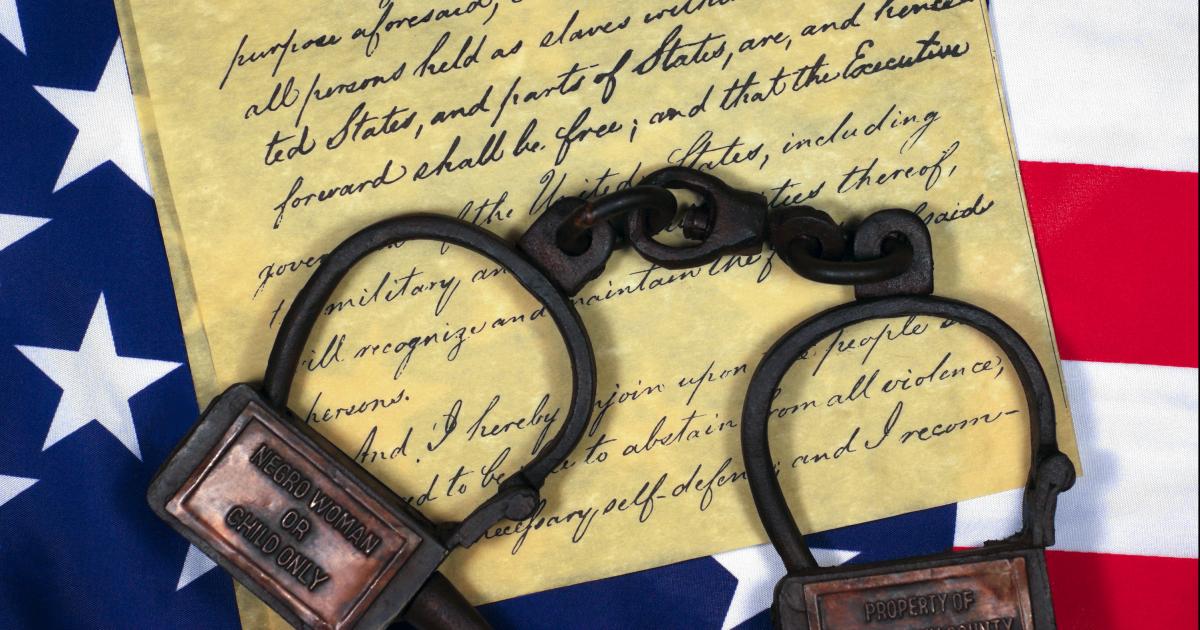

The roots of these disparities reach deep into America's history, into the dark periods of slavery and Jim Crow. The repercussions of these eras continue to affect the lives of Black Americans. Our study, "Jim Crow and Black Economic Progress After Slavery," sheds light on the long-term economic impact of these historical injustices, revealing a stark economic divide among Black families based on their ancestral history.

My colleague Hugo Reichardt and I delved into millions of records spanning 150 years for individual Black families, providing insights into their evolving economic status and the institutional factors their ancestors encountered. This data allowed us to assess whether a Black family had been enslaved until the Civil War and, after the abolition of slavery, to which specific Jim Crow regimes they were subjected until the 1960s.

We found that Black families enslaved until the Civil War have significantly lower income, education, and wealth today than those whose ancestors were free before the war. These "Free-Enslaved gaps" account for 20 to 70 percent of the corresponding Black-White gaps. Our findings emphasize the enduring effects of slavery and Jim Crow. Racial inequality in the United States is not merely the result of current policies or individual choices. It is deeply rooted in the nation's history.

While the first roots of these disparities among Black families trace back to the era of slavery, we found that state institutions after the end of slavery drove their persistence—regimes called Jim Crow.

Upon gaining freedom from slavery, Black families were eager to pursue formal education. As Booker T. Washington stated in 1907, "It was a whole race trying to go to school." However, Black Americans' ambition was met with fierce resistance, fueling the rise of the new anti-Black institution of Jim Crow.

Jim Crow aimed to lower Black economic progress by racially segregating virtually all areas of life, disenfranchising Black voters, and limiting Black Americans' geographic mobility.

The intensity of Jim Crow regimes often varied drastically across states. For example, Louisiana passed almost one hundred Jim Crow laws through 1950, while its neighboring state of Texas passed fewer than one-third of that number.

The largest category of Jim Crow laws targeted education directly. These laws racially segregated schools, unequally divided educational resources between Black and White children, and barred Black parents from participating in the local bodies that governed their children's education. Consistent with the difference in the number of Jim Crow laws that were passed, the quality of Black schools in Louisiana was far worse than in Texas.

Enforced in the Southern states until the mid-twentieth century, Jim Crow systematically disadvantaged descendants of enslaved people. Most families who had been enslaved until the Civil War resided in the states that adopted the strictest regimes after slavery ended.

This lack of economic opportunities during the Jim Crow era—especially the lack of access to education—is the leading factor in why those Black families have lower levels of education, income, and wealth today.

However, our study also offers hope: access to education can significantly improve the long-run economic outcomes for Black families, even for descendants of those who lived under the most restrictive Jim Crow regimes.

Around the 1920s, a philanthropic program started to build approximately five thousand schools across the rural South. These schools aimed to undo some of the harm caused by Jim Crow's restrictions on Black education. We compared the long-term outcomes of families whose children could attend such a school with those who could not. Our findings reveal that gaining access to a newly built school in the 1920s and 1930s closed the vast majority of the loss in human capital caused by exposure to strict Jim Crow regimes.

Even Black Americans today whose fathers had attended such a school in the mid-twentieth century are far more educated and have higher incomes and wealth than Black Americans whose fathers had not been able to attend. This discovery underscores the transformative power of education and its potential to help reduce racial inequality.

Our research has significant implications for present-day policy makers who aim to mitigate the disadvantages faced by the descendants of enslaved people.

First, our findings underscore the significance of disparities within racial groups that race-specific policies may not adequately address. Take college affirmative action as an example. Studies have shown that the more selective a college, the less likely it is that Black students are descendants of enslaved people.

While affirmative action enhances racial diversity on campuses, it may fall short of reducing the disadvantages experienced by descendants of families enslaved until the Civil War. Considering an applicant's race and socioeconomic background could make affirmative action more effective.

Second, our study highlights the importance of ensuring access to quality education for all. Policies to improve educational opportunities for Black Americans could play a crucial role in addressing the racial income and wealth gaps.

During the Jim Crow era, the new construction of schools was especially effective in regions where Black children were most deprived of educational resources. Our research also indicates that such interventions can have substantial effects across generations. Overlooking these effects could result in policies with a smaller scale than optimal ones.

Third, there has been a recent resurgence in discussions around the concept of reparations, or wealth transfers, to the descendants of enslaved individuals. In our study, we emphasize that any evaluation of slavery's legacy should consider both the timing and location of a family's emancipation—how long they were enslaved and the extent of their exposure to Jim Crow laws following slavery. Our research reveals that the present-day circumstances of Black families are significantly influenced by the timing and location of their ancestors' freedom.

It's important to reiterate that our study primarily quantifies the additional challenges faced by those whose ancestors were enslaved until the Civil War compared to those who gained freedom earlier. It's worth noting that many free Black Americans had been enslaved in earlier periods, and all Black Americans faced discrimination due to slavery and Jim Crow, regardless of their specific family history.

While some argue that reparations should only be given to those who can trace their lineage back to enslaved ancestors, our findings suggest that post-slavery institutions also negatively impacted Black Americans whose ancestors were free before the Civil War. This group may find it more challenging to provide proof of their ancestors' enslavement, as it occurred decades before the Civil War.

In sum, our results serve as a reminder of the enduring economic impact of slavery and Jim Crow laws on racial inequality. It underscores the need for policies that address these historical injustices and promote economic equity. As we strive to build a fairer society, we must understand and address the historical roots of today's economic disparities.

Indeed, even "race-blind" policies can inadvertently interact with differences caused by historical institutions. Without this crucial understanding, systemic discrimination—the exposure to ongoing discrimination because of past injustices—will likely continue to be at the core of racial inequality in America.

Read the full working paper here.

Lukas Althoff is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR). He will be joining Yale School of Management as an Assistant Professor of Economics in 2024.

Research briefings highlight the findings of research featured in the Long-Run Prosperity Working Paper Series and broaden our understanding of what drives long-run economic growth.