- World

- International Affairs

- History

To many Americans Juan Domingo Perón was the husband of Evita, the siren who gave her name

to a flashy musical and film. "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina," Evita wails in the show's most memorable song, and the audience weeps.

But when we leave Broadway and Hollywood for the serious accounting of history, we find that Juan Perón stands on his own. By any measure he was the dominant personality in modern Argentina and one of the giants of twentieth-century Latin America. And the world's foremost collection on Perón, his wives, and the Peronist movement is located in the archives of the Hoover Institution.

Perón rose from the ranks of Argentina's military officers to be elected president in 1946. He held office until 1955, when the military forced him into exile abroad. In 1973 he returned to the presidency, which he held until his death the following year. Perón's second wife, Evita, died in 1952; Perón was thus succeeded on his death by his third wife, Isabel, who was herself overthrown by the military in 1976 as Argentina slid into what became known as its "dirty war."

Perón took office as a populist nationalist who promoted a "third position" in the world--led, of course, by himself--that was independent of both "capitalism" and "communism." Much influenced by Mussolini, he expanded the state-dominated economy introduced by his predecessors. It is now widely accepted that Perón's policies dragged Argentina--a nation of vast natural resources--out of the first world and into the third. In the words of Venezuelan Carlos Rangel, Perón was an "unscrupulous demagogue, one of the most pernicious false heroes of our Latin American history." Yet such is the hold of Perón on Argentines even today that Carlos Menem, elected president of Argentina in 1989, proudly calls himself a Peronist, even though Menem has instituted free market reforms intended to roll back the statist apparatus that Perón himself set in place.

Any attempt to understand Argentina's grand and often tortured history, and its significant international influence, must deal with Perón and his legacy. Hoover's original core collection on Peronism, assembled by longtime Curator Joseph Bingaman, includes thousands of books and pamphlets published by and about Perón in Argentina and abroad.

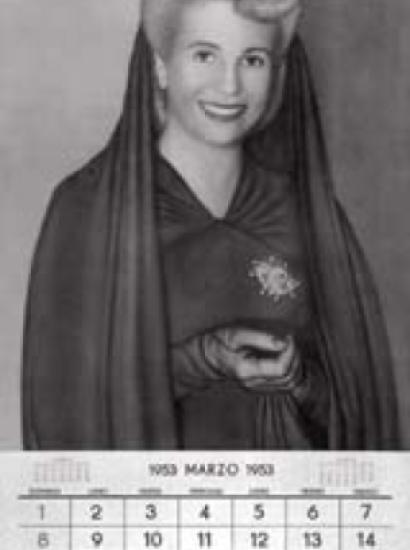

During my own twelve years as curator of the Latin American Collection, I have focused less on books and pamphlets and more on archival materials, ranging from documents in Perón's own hand to photographs of the young dictator and his glamorous second wife--including a calendar featuring a different photograph of Evita for every month of the year. These more recent additions to our Perón collection include materials covering the following topic areas.

Perón's "First Words"

From 1931 to 1933 Perón was a professor at the Advanced War College, where he taught courses ranging from the Napo-leonic to the Russo-Japanese Wars. Hoover has hundreds of pages of examination papers from these courses, written by one of Perón's best students and graded--often with extensive comments and annotations--by Perón himself. These exam papers represent the earliest record of Perón's views on an array of issues, including international affairs, the relationship between the military and politics, and the strategies and tactics of military conflict. In one place Perón noted that Napoleon's great strength lay in his ability to develop, unite, and effectively control his forces, a skill the Argentine leader honed throughout his life.

Perón's Presidency

Complementing the thousands of published materials in the library that date from Perón's long presidency, the archives contains letters and other materials either written by Perón himself or intended for the president's eyes only. These include a long intelligence report on the increasing opposition to his government from 1954 to 1955 within the Catholic Church.

Of particular interest are three documents that were on his desk on the day in 1955 when the military drove him from office. Two of the documents are three-page manuscripts in Perón's own hand, evidently drafts of speeches or articles. The first, entitled "Continental Solidarity," is in the roughest form. The second, "Economic Cooperation," appears more nearly completed and argues that the proponents of imperialism follow both political and economic roads, "developing an integral power and dominion over their colonies in order to exploit them economically to benefit

the metropolis." This amounts to an early version of the dependency theory that Latin American policymakers and scholars embraced for several decades. Capitalism, Perón continues, brings with it the "inhumane exploitation of men and peoples and is the cause of all the evils of the 20th century, including communism." As long as this capitalist and imperialist exploitation continues, he concludes, "it will be difficult to fight against the red danger."

The third document is a typescript bearing the title "The Opportunistic Attitude of the United States toward the Economic Development of Latin America." Here Perón fleshes out the argument that the United States has "systematically refused to collaborate in a mutually productive way with the Latin American countries in an organic plan to diversify their economies by promoting the exploitation and industrialization of their resources."

The archives also contains the personal papers of one of Perón's most influential ministers, Juan Atilio Bramuglia. One scholar of Peronism, Raanan Rein, calls Bramuglia "the most eminent and the most talented minister in Juan Perón's first government." Besides being a party organizer, Bramuglia was for a time Perón's foreign minister. In 1948 he was president of the United Nations Security Council. Using the Bramuglia collection, Raanan Rein has been able to trace in detail the ideological, personal, and intergenerational struggles at the top levels of Perón's government, particularly during the U.N. debates on Palestine and the Berlin crisis.

Exile

Covering Perón's years in exile, the archives contains forty-nine major letters from Perón. The letters that date from the early years of exile are to Hipólito Paz, Perón's former foreign minister and ambassador to the United States; to Chilean writer, politician, and feminist María de la Cruz; and to Stanford University professor, now Hoover fellow, Ronald Hilton. The letters later in the exile are to journalist and Peronist Américo Barrios.

On his first Christmas in exile, Perón wrote to de la Cruz from Caracas, Venezuela, lamenting that while in power he had been too tenderhearted. "I am persuaded the great mistake I made was trying to carry out a bloodless revolution." He warned of an inevitable "catastrophe, bloody and violent" in Argentina with "great bloodletting and terrible reprisals that will eliminate the

parasitical class. There aren't enough trees in Buenos Aires to hang these people." A year later he wrote to de la Cruz: "We have to be prepared to witness the deaths of many hundreds of thousands [muchos cientos de miles] of people. Without this there is no solution." In February 1956 he wrote to Paz that Peronism needed to make use of sabotage, deception, stoppages, strikes, and boycotts, with "individual secret actions destined to bring on a true guerrilla war in which the dictatorship never encounters a visible enemy. . . . We will not try to win the war with a single battle but with thousands of isolated encounters." In both the 1956 and the 1957 letters to de la Cruz and Paz appears a line that Perón used often, always underlining every word: "At this time in Argentina, the historical necessity is the national insurrection."

In Perón's letters to Barrios, he comments less on the need for "insurrection" and more on the intellectual underpinnings of his movement. By 1964 Perón was planning what he called "Operation Return." A letter to Barrios and two other top supporters dated June 10, 1964, formally appoints Barrios president (and the other two secretaries) of the Institute of Justicialist Doctrine, the "official organism of the Peronist movement for the elucidation and diffusion of doctrine and for political, economic and social studies."

Peronism Today

Although the Hoover Institution continues to collect materials from Perón's years in power and exile, our focus has expanded to include documentation of the Peronism represented by the government of Carlos Menem. In 1989, the morning after this Peronist was elected president, amid terrible economic chaos nationwide, Menem embraced free market reforms. In two terms in office, Menem has dismantled many of the institutional barriers Perón had raised to economic productivity and prosperity, not least by opening doors to foreign investments. Among the new archival acquisitions are many "oral histories," such as my interviews with Domingo Cavallo, the former economy minister and the architect of Argentina's capitalist reforms, and a long discussion of Argentine economic policies between Cavallo and Hoover Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman.