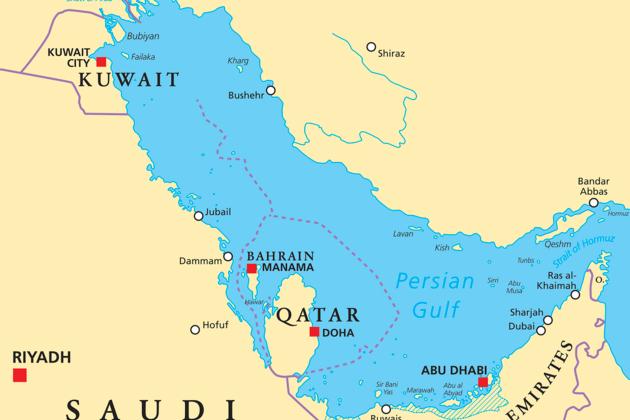

In recent years and months, the Arabian Gulf has been transformed. Saudi Arabia is normalizing its relationship with Iran; China is supporting GCC-Iran normalization; the UAE withdrew from the Combined Maritime Forces which it had participated in for over 30 years; the Arab League, which ousted Syria from the organization in 2011, has unanimously brought it back into the fold. The standing of President Recep Tayyib Erdogan of Turkey has changed drastically from a bitter foe three years ago to a strategic ally to the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. How could political and security polarity change in less than five years, and how does the US factor into these changes?

The Many Faces of De-Escalation

De-escalation is possibly the most common buzzword in Middle East policy-making circles nowadays. The term became contentious after the agreement in Beijing between Saudi Arabia and Iran to resume diplomatic ties. Some experts saw it as a sign of a “Post-American Middle East.” A more pragmatic view would be to see this as a sign that defeating Iran ultimately will not work and therefore a different approach is needed.

In May 2019, four ships were sabotaged off the port of Fujairah in the UAE; evidence suggested the attack was state-sponsored. However, Foreign Minister His Highness Sheikh Abdulla Bin Zayed, after meeting his counterpart in Moscow, emphasized the need for de-escalation, and stated there was no hard evidence tying Iran to the attack, despite President Trump’s statement that “Iran did do it.” This was a clear indication that the UAE was avoiding a full-blown military confrontation with Iran, despite US support.

The concept of de-escalation has become the basis of a new strategy, one that Anwar Gargash, former UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, outlined with regard to the withdrawal from Yemen in July 2019 and likewise used to describe the UAE approach towards Iran in September 2019.

The same concept can be seen in the UAE’s approach to Turkey. The visit of UAE National Security Advisor Sheikh Tahnoun Al Nahyan to Ankara in August 2021 came at a time when relations between the two countries were frayed. This meeting was soon followed by another three months later between His Highness Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed, President of the UAE (then Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi), and President Erdogan. Relations between Ankara and Abu Dhabi moved from contentious to cooperative. Earlier, Turkey had accused the UAE of funding the coup d'état attempt in 2016, but by 2023 the two countries were signing a strategic partnership agreement worth $50 billion.

De-escalation can be seen on a larger scale as well. The most complex arrangement came in the form of the Abraham Accords in September 2020. The Abraham Accords are not just a peace agreement similar to the agreements Israel signed with Egypt in 1979 and with Jordan in 1994, mainly because the UAE doesn’t share a direct border with Israel and was not directly engaged in a war with the Jewish state. Though Sheikh Abdulla Bin Zayed described the Abraham Accords as “based on a simple premise,” they represent a profound change. They are not just a peace treaty between two countries, but part of a wider strategy to reduce the conflict from an existential conflict of identity to a political conflict that can be resolved through negotiation.

New Calculus in the Gulf

Though traditionally more of a confidence-building measure, de-escalation marks a fundamental overhaul of the zero-sum calculus that has underpinned geopolitical tensions in the region. Countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia have cultivated new relations with Israel and Iran at the same time. A similar trend can be seen in UAE relations with both India and Pakistan and in its relations with Ethiopia and Eritrea. On a global scale, this is the approach the UAE is taking towards China-US relations and its relations with both Russia and Ukraine. More than a mere tactic, this represents a transformed understanding of how geopolitics is changing in the region and globally.

This change is not risk-free. Adopting a new calculus in international relations will have a tectonic impact on the way a long-established matrix of interests and risks has shaped the world, and this is especially true for the relationship with the US. While the UAE de-escalation with Israel was celebrated in the US, the de-escalation between Saudi Arabia and Iran has been met with far more skepticism from Washington. While the White House welcomed the deal upon announcement, the US was quick to send F-16 fighter jets to “protect ships” in July and then to send 3,000 troops to the Red Sea amidst signs of disagreement between Kuwait and Iran over the Durra marine gas field. This redeployment of US military assets stands in stark contrast to President Biden’s celebratory remark in his opinion piece in the Washington Post before his visit to Jedda where he stated that he is “ the first president to visit the Middle East since 9/11 without U.S. troops engaged in a combat mission there.” So, what has reversed the US position from withdrawing Patriot missiles from Saudi Arabia during the Houthi attacks to redeploying military assets in the region?

Is it all about China?

The US reaction to the Saudi rapprochement with Iran is arguably more about China than Iran. The Gulf countries, particularly the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have expanded trade and strategic relationships with China and Russia, which analysts have treated as a “stress test” for their traditional alliances with the US. Abu Dhabi froze discussions over the sale of the F-35 due to US concerns over its Huawei powered 5G network. This was a clear sign that the relationship structure was shifting. Meanwhile, the US administration accused the UAE of allowing China to build a secret military port. Similar intelligence was also leaked by the US administration suggesting that the UAE is colluding with Russian intelligence against US interests, sending a message that the growing relationship with China and Russia is counter to US traditional influence in the region.

Erosion of US Position in the Middle East

China aside, one cannot discount the impact of the rapprochement with Iran on the US strategic position in the Arabian Gulf. US policy in the region has been Iran-centric, both in its attempt to isolate Iran in the region, a pillar of the Bush administration policy, or to engage with it, the foundation of the Obama administration’s policy. The current regional approach to Iran is based on ending its isolation and changing the focus of engagement from security to connectivity. But this contributes to the undermining of the US position in the region.

The US is no longer the primary economic partner of the GCC, having been surpassed by China; it has declared the de facto Saudi leader a “pariah”; and American policies such as “no boots on the ground” and “burden sharing” have reduced the credibility of the US as the security guarantor to the GCC. At the same time, the defense purchases of the GCC have been marked by a diversification away from US equipment.

Attempts by President Biden to institutionalize the security relationship with the GCC, through floating the idea of a Middle East NATO-like collation or using it as an enabler for security cooperation with Israel, have also not met with great excitement in the region.

Replacing US Strategy, not the US

In considering the four pillars of any strategic relationship—political, security, economic and cultural—the UAE and other Arabian Gulf nations have not changed their views on the importance of the US as their primary strategic partner. While there is an obvious “detachment” from recent US policies among Gulf states, this should not be mistaken for a desire to change the fundamental relationship with the US.

Gulf countries are actively pursuing a connectivity agenda that sees a world order based on interconnectedness, not polarity. This vision requires developing connectivity arteries between economic hubs such as the US, Europe, Latin America, India, China, Russia, Japan, South Korea, Indonesia and others. It is the driver behind the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs), and the basis of the trilateral and mini-lateral formations that the UAE has been developing, including the well-intended but less effective I2U2 (India, Israel, UAE and US).

It is easy to depict the US position in the region as challenged, or even eroding. It is also easy to depict regional states’ “muscle flexing” as a major factor in that erosion. Yet seen from these states’ perspective, the US has reduced its political relevance because of its continuous attempts to polarize the world into “friends, foes and fence sitters.” The US has not made an effort to understand the requirements of this region for knowledge transfer, economic diversification, and connectivity, seeing itself above all as a security provider rather than a partner.

As the concept of security continues to change and de-escalation marks the arrival of a “New Gulf,” the US will need to make sure that de-escalation does not turn into another kind of gulf separating it from some of its closest friends.

Mohammed Baharoon is the director of Dubai Public Policy Research Center (b'huth), a UAE based think tank that looks at the interaction between public policy and foreign policy.