This week, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani decided to fire his entire cabinet, after he and presidential runner-up Abdullah Abdullah failed to agree on a new slate of cabinet ministers. As part of the power-sharing agreement brokered by the United States in September, Abdullah Abdullah was made co-equal with Ghani in selecting the cabinet. At the time, American officials hailed the sharing of power as a welcome change from the one-man rule of Hamid Karzai, Ghani’s predecessor. Karzai’s cabinet governed while Ghani and Abdullah haggled over the new cabinet, and when the negotiations went on well past the original deadline, the incumbents increasingly focused on other matters, leaving governance and security to drift. This paralysis helped account for the recent decline in security across Afghanistan.

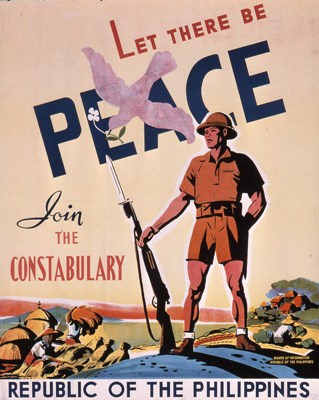

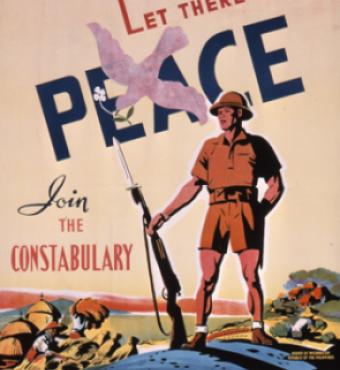

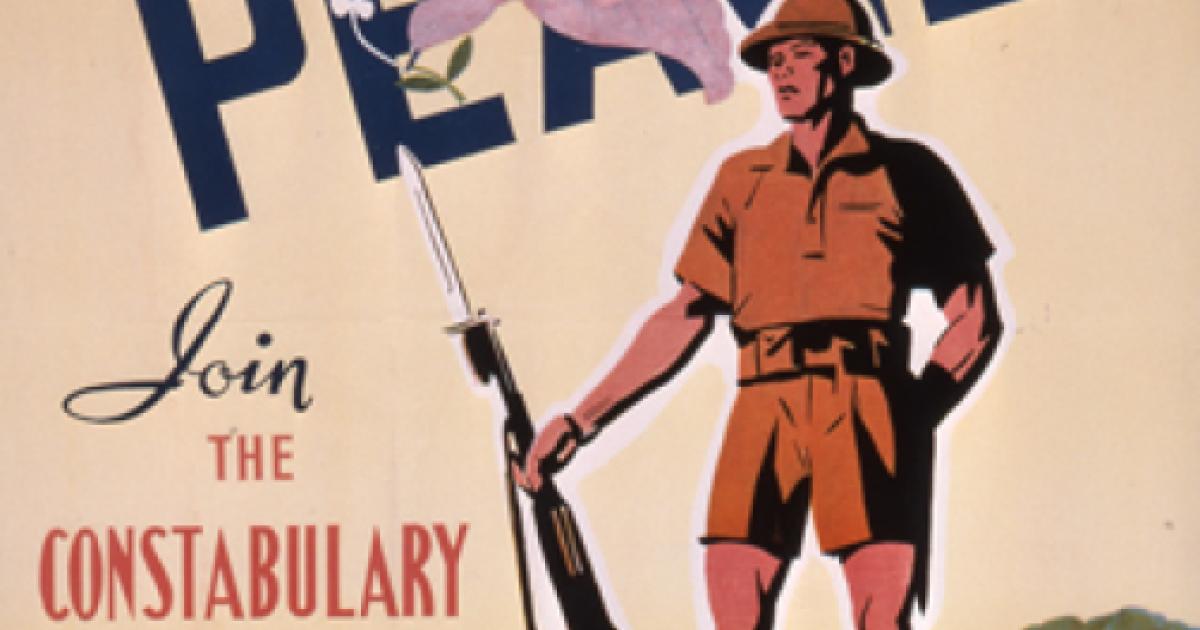

History gives great cause for concern about cabinet-level troubles at a time of insurgency, for ministers of Defense and Interior have often been critical to the success or failure of counterinsurgencies. Those ministers are usually responsible for the most vital of counterinsurgency tasks—appointing commanders in the military, police, and other security forces. During the Huk Rebellion, for instance, the Philippine government saved itself in 1950 by replacing the sclerotic Secretary of Defense with a dynamic young man named Ramon Magsaysay, who in turn replaced a slew of ineffectual officers and governors with men of competence and resolve. In Afghanistan a decade ago, Hamid Karzai conducted a Cabinet purge that had much to do with the country’s ensuing deterioration.

In an effort to rescue the situation, Ghani is taking on some of the work of the cabinet ministers himself, including personnel decisions. But if he continues to do the work of the cabinet, he may find himself in the same boat as another recent chief of state who took over the security ministries, Iraq’s Nouri al-Maliki, with large segments of his former partners in government rising against him.

The current crisis also brings to mind the change in power in Vietnam in 1963, when the autocratic Ngo Dinh Diem was ousted and the South Vietnamese attempted to govern by committee. The United States had incited the coup that ousted Diem, in the belief that rule by strong man had become passé. The change led to several years of political chaos, and was followed ultimately by a return to autocracy, in recognition that a strong man was better than a committee in ruling a fractious society faced with mortal enemies inside and out. Unfortunately, Afghanistan could be headed on the same trajectory.