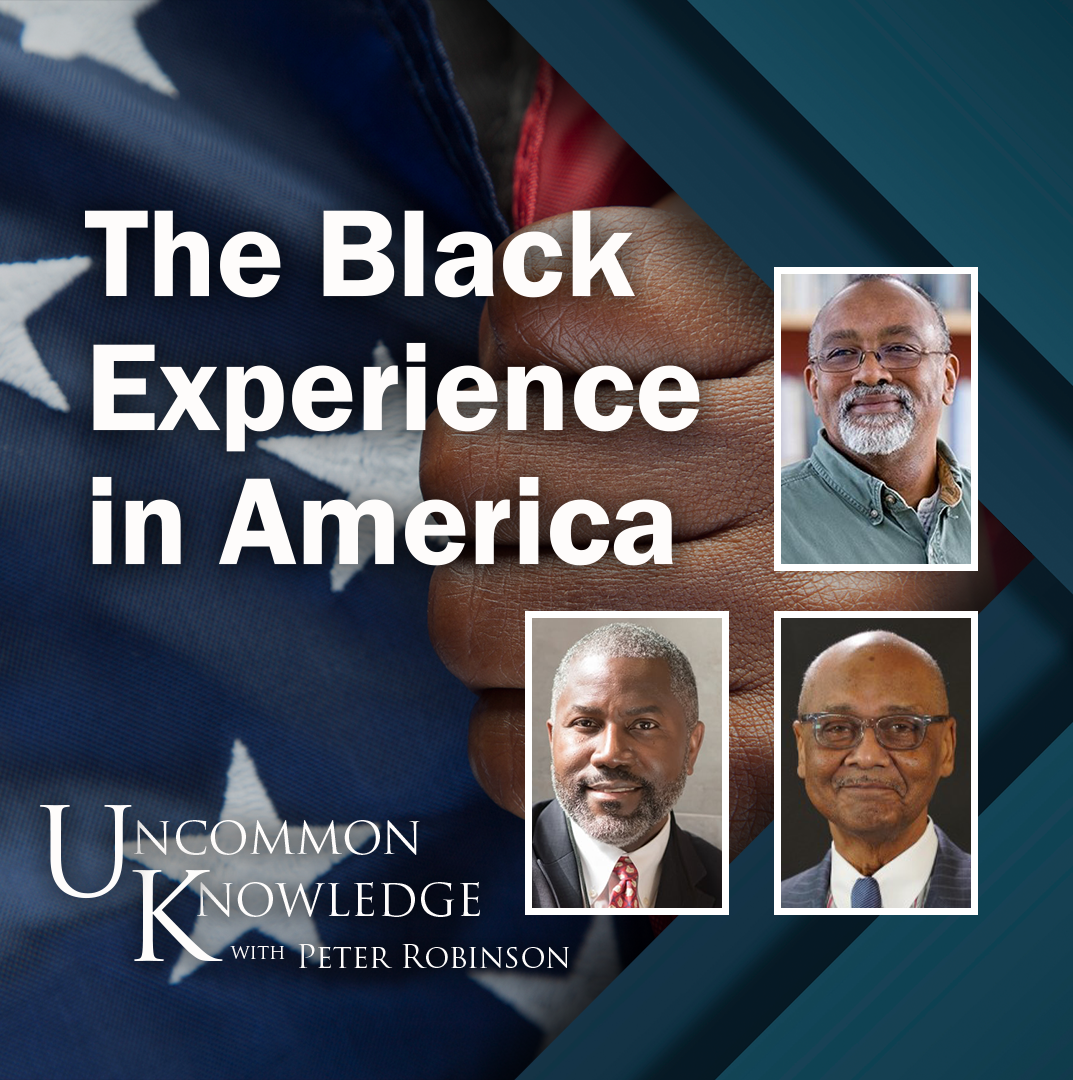

- Civil Rights & Race

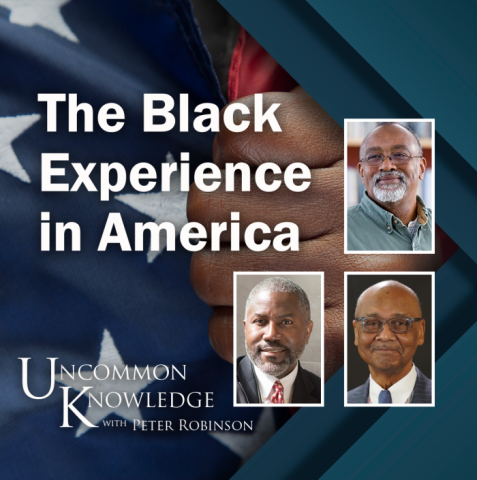

If there were a Mount Rushmore of American Black intellectuals, the three guests on this show would certainly be on it: Glenn Loury is a professor of the social sciences in the Department of economics at Brown, a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution, and the host of his wildly successful podcast, The Glenn Show. Ian Rowe is the cofounder of Vertex Partnership Academies and the author of the new book Agency: The Four Point Plan (F.R.E.E.) for ALL Children to Overcome the Victimhood Narrative and Discover Their Pathway to Power. Robert Woodson is the founder of the Woodson Center, an organization devoted to “empowering community-based leaders to promote solutions that reduce crime and violence, restore families, revitalize underserved communities, and assist in the creation of economic enterprise.” In this wide-ranging conversation, the three men debunk The 1619 Project, advocate for the restoration of the Black family and the Black church, describe their own very different upbringings and formative experiences, and discuss the many reasons why they are optimistic about the future of Black Americans, despite the narrative commonly expressed in the media.

Recorded on May 13, 2022, at the Old Parkland Conference in Dallas, Texas.

To view the full transcript of this episode, read below:

Peter Robinson: From the title page of Nikole Hannah-Jones essay, Introducing the 1619 Project quote, "Our founding ideals of liberty and equality were false when they were written." The United States of America, a racist fraud. With us today, three African American intellectuals who do not buy it. Glenn Loury, Ian Rowe, Robert Woodson on Uncommon Knowledge now. Welcome to Uncommon Knowledge. I'm Peter Robinson. We're shooting today from the Old Parkland Conference in Dallas, Texas. Glenn Loury grew up in a rough neighborhood on the south side of Chicago and became a tenured professor of economics at Harvard at the age of 33. Dr. Loury now holds a chair in social sciences and economics at Brown. He also hosts a weekly podcast on the Ricochet Network, The Glenn Show. Glenn Loury holds degrees from Northwestern University and MIT. Ian Rowe grew up in New York and describes himself as quote, "A proud product of the New York City public school system." A fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a visiting fellow at the Woodson Center. We're coming to Woodson. Ian Rowe is the co-founder of Vertex Partnership Academies, a new group of high schools that opened in the Bronx this very year. He's the author of the new book "Agency" published this month. The book, and here I quote from Mr. Rowe own material "Seeks to inspire young people of all races to build strong families and become masters of their own destiny." Ian Rowe holds degrees from Cornell and Harvard. The founder of the Woodson Center, Robert Woodson grew up in Philadelphia during the '40s and '50s, participated in the civil rights movement in the '60s and has since the '70s emphasized neighborhood empowerment over government action in improving the lives of African Americans. Two years ago, he countered the New York Times 1619 Project by founding 1776 Unites. Robert Woodson holds degrees from Cheney University and the University of Pennsylvania. Glenn, Bob, and Ian, thank you for joining me.

Robert Woodson: Thank you for having us.

Glenn Loury: Good to be with you.

Peter Robinson: All right. The first question takes a moment to set up, but I'll set it up and just toss it over to you. We're recording today as I mentioned at the Parkland Conference in Dallas, a conference that is considering the state of African American lives in America, in light of a conference that took place actually 42 years ago, would've been 40 if COVID hadn't intervened, and this conference had taken place on time. But the Fairmont Conference of 1980, which Bob Woodson attended. Thomas Sowell, our friend and hero, Thomas Sowell at that 1980 conference quote, "One of the problems in dealing with programs for blacks is that vast empires can be built on these programs. These programs definitely prevent poverty among bureaucrats, economists, statisticians, and others." So that sums up the spirit of the conference of four decades ago. Not politics, but economics replaced dependence on government programs with education and work. Since that conference, good news. The proportion of African Americans living in poverty has fallen from 30% in 1980, the year of that conference to 19% today. But then there is this, income. According to the census bureau, median white household income in 2017 was $68,000 a year. And median black income was $40,000 a year. 40 years later, that gap. Educational attainment, according to a 2019 study in the average school district, white students scored an average of 1.5 to two grade levels higher than black students. Again, after four decades, a gap. In these last four decades, the Cold War has ended. The American economy has more than doubled in size. A technological revolution has swept the world. And yet these gaps between white and black Americans just seem frozen. How come Glenn?

Glenn Loury: Well, they're not exactly frozen, although they are such as you described, we do have gaps. I think that we have to consider what the government can do through law and policy and what it cannot do. I think that we have largely accomplished what the government can do in terms of creating a level playing field of opportunity between blacks and others.

Peter Robinson: Equality before the law.

Glenn Loury: Correct. Non-discrimination, voting rights, open equal access, but there are things the government cannot do. The government cannot make families stay together. The government cannot raise children. It can't influence a culture that may encourage behaviors that are counterproductive. It can't break down old habits. So in a way, the ball is in our court now, I speak of African Americans. The society is open and fair and free to a very great extent. Otherwise, people wouldn't be voting with their feet in the millions and tens of millions to try to come here. But we still African Americans have our work cut out for ourselves, educating our children and taking care of our own business. That anyway is the argument that I'd be inclined to make 42 years after Thomas Sowell and others gathered here, gathered at Fairmont to discuss these issues.

Peter Robinson: Bob, you grew up in a time segregation, you grew up in Jim Crow.

Robert Woodson: I really did in a low income black neighborhood in Philadelphia.

Peter Robinson: And so are you gonna buy Glenn's argument?

Robert Woodson: Let me tell you--

Peter Robinson: That discrimination is now over?

Robert Woodson: The question is how did we thrive in the presence of segregation? Yes. And the greatest declines are occurring during the time of desegregation. I grew up in 1937, I was born in the middle of depression. I never heard a gun fired in my life in the time I was there through high school.

Peter Robinson: You were born in 37.

Robert Woodson: Born in Philly, 1937. I never heard a gunfire at all. 98% of all the households had a man and a woman raising children. I never heard of an elderly person being mugged in my neighborhood. I never heard of a child being shot in their crib. All of these occurred that between 1930 and 1940, when racism was enshrined in law, black America had the highest marriage rate of any group in society and elderly people could walk safely there. And Thomas Sowell pointed out that the largest decline in poverty in the black community occur between 1945, Glenn. It reduced some 82% down to 40 and then even further. And all of this came to a halt in the '60s with a war in poverty. That's when we saw a dramatic change in the composition of families, also income made a reduction in poverty. So, I know that what, 50 years of post slavery... 100 years after slavery, it didn't destroy our families, but the last 50 years you've seen rapid declines and we document why that happens.

Peter Robinson: Ian. So we get the civil rights movement, gives us equality before the law, correct?

Ian Rowe: Yeah.

Peter Robinson: We grant that. And then with roughly the same time in the '60s, we get the great society and a vast expansion of the welfare state, and much of that is directed toward African Americans. And Bob Woodson, and I am not about to argue with a grand old man here, Bob Woodson, Bob Woodson says that Glenn says equality before the law, of course, is good and has been substantially achieved. Is that fair?

Ian Rowe: Yeah.

Peter Robinson: And Bob Woodson says all of this, no matter how high minded, no matter how well intentioned, this vast apparatus of welfare has left us African Americans with shattered families, crime rates we didn't have. How do you explain all this?

Ian Rowe: Well, I think it's first important to establish that not all African American families are living in poverty.

Peter Robinson: Of course.

Ian Rowe: Or shattered. It's an important, 'cause the narrative often seems to be when we come to this subject, we immediately move to that segment of the black community that has been steeped in pathology in some way. And yet since the '60s and prior, black doctors, lawyers, accountants, professionals--

Peter Robinson: So there's the president of the United States.

Ian Rowe: And the president and even the vice president. So we have to be as obsessed with the success of the black community, to understand what are the factors that have driven that level of success, as we are seemingly as obsessed with that segment of the black community that has not been successful. And you started off your comments by talking about these persistent gaps.

Peter Robinson: These gaps. Yes.

Ian Rowe: And it's important to talk about those because there are. And I , as someone who has run schools in the heart of the south Bronx, I'm very well aware of these persistent gaps between black students and particularly white students. But it's important to note that in the entire history of the national assessment for educational progress, which is the nation's report card, it's still the case that in 2019, prior to the pandemic, only 37% of all American kids, are reading at grade level and even white kids have never been higher than about 44% of white kids reading at grade level. So what's interesting about that, it's unlikely that systemic racism is the reason right that white kids are not reading at grade level. So the question is what are the factors beyond race that are driving low performance outcomes for kids of all races? And to the degree that we can start to distinguish this idea that disparity must equal discrimination. We need to break that because that mono causal type of thinking shrouds all of these other factors that are so important in the black and other communities. Strong families, access to school choice, high expectations in curriculum. These are the things that I think if we were to, in a sense not to ignore the impact of racism, but put it in its proper context to really ask the question, to what extent does racism really explain these disparities given some of the achievements of equality under the law, and the levels of success that do exist within the black community, and have hard honest conversations about how these other factors are really driving these disparities.

Peter Robinson: Let's go to the 1619 Project, because one aspect of understanding the black experience in America is understanding America, right? New York Times editor, Jake Silverstein introducing the 1619 Project. He wrote an essay that introduced it, quote, "1776 is the year of our nation's birth. But this fact which is taught in our schools and celebrated every 4th of July is wrong. And the country's true birth date was in 1619, the year the first slaves reached North America." So the New York Times knows what the problem is. The country was racist from the get go. Okay, now here's a tweet from brother Glenn over here. After the 1619 Project won a Pulitzer Prize. Loury has the effrontery to post this tweet. "A group of scholars, myself included are calling on the Pulitzer board to revoke that prize." You better explain yourself, the New York Times come on.

Glenn Loury: Well, it was a Pulitzer Prize for a piece of journalism that was flawed. This had to do with the essay that Hannah Jones pinned to open the magazine special issue in which she alleged that the generation of founding Americans who fought the revolutionary war against Britain did so in order to preserve slavery, or because they felt that Britain was a threat to the preservation of slavery and the colonies. And distinguished historians have come forward to say that that is simply false. So I thought and think that veracity and accuracy of historical argument should be at least a necessary precondition for the awarding of a Pulitzer Prize. But I wanna say something else, if I may.

Peter Robinson: Please.

Glenn Loury: Which is that the reason that something like the 1619 Project could have such cache as it does have is because of the disparities. The disparities are the underlying fuel to the political bonfire that we saw after the killing of George Floyd in 2020. The disparities don't address the problems that are affecting all Americans. I agree with Ian about that, but they are nevertheless, a very important reality. And that has political consequences.

Ian Rowe: The thing that, and I think this is at the heart of the issue, the disparities have to be addressed. The question is, what's the theory upon which why those disparities. Indeed. In 1619 Project, they argue that the United States has anti-black racism in the very DNA of the country. So think about that. So for them, there is no other explanation, all of these things in terms of family structure, access to great schools, high expectations, none of that matters relative to this force.

Peter Robinson: Let me quote you in, This is a piece you wrote about the 1619 Project. "As educators," And again, you run charter schools in the Bronx. "As educators, we must reject the tired ideas of the 1619 Project." I love this. "We do our scholars no favors by treating them as victims.

Ian Rowe: Oh, in my entire 10 years of running schools, I never had a single parent ask me to make sure in the curriculum, we teach our kids that they're just gonna be victims of this white power structure, abandoning their agency.

Peter Robinson: Robert Woodson, on the 1619 Project, as the Woodson Center scholar Delano Squires has noted. "We are now beset," Listen to this. It's not often, I wish I'd written something myself, but this is really good. "We are now beset by white liberals who are looking for absolution from sins they didn't commit, and black liberals who are looking to be affirmed for injustices they didn't suffer." Bob, explain yourself.

Robert Woodson: I mean, all of these, this false narrative driven by elites on both sides who are victim signaling. And also I think publishing a false narrative that is untrue. The assumption is that a lot of the challenges facing a lot of low income communities of out of wedlock birth and what have you, is directly attributed to the legacy of slavery and discrimination. And so what we did--

Peter Robinson: And that cannot be true because you knew an African American community when you were a kid, that didn't suffer for many of that.

Robert Woodson: No.

Robert Woodson: And we all could read, you know. But we also, in our essays did not want to just offer a debate. We wanted to offer a counter narrative that was inspirational and aspirational. We tell examples of in 1943, when Eleanor Roosevelt, there were no black Naval officers. And so Eleanor Roosevelt persuaded her husband to force the Navy to train them. So they trained 16 college educated men. Well, the Navy said, "We're going to give them in eight weeks, what we give the white cadets in 16 weeks." So when these men found out about it, they covered the windows and their barracks and stayed up all night and studied. And when they were tested, they scored in the 90th percentile. They said, "Oh, they cheated." So they took them individually. They scored in the 93rd percentile and eventually they were commissioned. But those test scores are still the highest ever obtained in that school. And there are other examples from the past where under horrendous circumstances, we outperformed, we performed in the presence of these obstacles. And so these are very important lessons for people because people are motivated to change and improve when they see victories that are possible, not constantly reminding them of injuries to be avoided.

Peter Robinson: So Glenn, if we could wave a magic wand and give African Americans... All Americans for that matter, but we're talking about African Americans because we've got these disparities, some large percentage of kids raised to the age of 18 in a home with both parents present, instead of a tiny percentage, make it 60, 70%. There are gonna be divorces, families have to... Fine, let's get it over half, give them decent schools, really three things as far as I can tell, I'm putting this to you. I'm not announcing it. I'm putting it to you for your correction and amendment. And then the third, we let them grow up in neighborhoods that are safe. If we do those things, those are the three things, now that there is fundamentally equality before the law, we could just sit back and let it rip. Couldn't we?

Glenn Loury: From your mouth to God's ears. Indeed we could. And you know, there's no reason to expect that in an ideal society, every group is going to come out in equal wealth holdings and equal professional achievement and so on. Disparities are not discrimination. Disparities are not even necessarily problematic, but the magnitude of the difference at the low end of the socioeconomic spectrum of experience for African Americans and others is deeply troubling. And I think the three things that you named, safety and security in your property in person, a place where your children can realize their full human potential through assiduous attention to their development. And a home environment that is relatively stable, that has 48 hours a day of parental supervision time, and not 24 hours a day, that has if necessary two salaries to put bread on the table and keep a roof over the heads, and not one. That models for one's children, what healthy family life looks like that has norms and expectations about behavior that are passed on from parents to children. Sure. We'd be okay.

Peter Robinson: We'd be okay. So here, I've got a lecture that you delivered in 2012. "Raising the issues of morality and values is vitally important. The family and church..." You two, listen to this too, 'cause I'm gonna come to you in a moment. "The family and church are the natural sources of moral teaching. Indeed the only sources." Okay. So here's the problem. If we all are in agreement that we know, actually, if we can give African American kids today, the kind of neighborhood in which Bob grew up some years ago, I won't name the years Bob, but some years ago.

Robert Woodson: I'm proud of it.

Peter Robinson: But how do you do it? How do you put the family back together for that matter? What can we do to reconstruct the African American church? I mean, I'm a white guy and I was grew up on hymns that were in those days called Negro Spirituals. And I was told and growing up in Upstate New York in a white community, I was told of the importance of the black church and how African Americans endured slavery because of their deep spiritual, all of this is true, but how do you put it back together?

Glenn Loury: You say, what can we do? And my answer is who are we? The collective way of the United States of America through its institutions, its government and its policies can do relatively little. There's some fiddling around the margin. There's a marriage tax. You might not want to have policy that makes it economically rational for people to avoid marriage and so on. There's the, when the state speaks, what does it say? Kind of messaging where through public programming of one sort or another, you can affirm certain values, very thin values, not something that violates the sectarian differences between us in terms of faith, but at its base, in terms of the conveying of norms and the teaching of a way of life. That's not something that the large we can do. That's something that the communal, we, it seems to me has to do. You say, how can we restore our churches? Well, we can't restore our churches, but we can.

Peter Robinson: Bob.

Robert Woodson: I guess I'm a radical pragmatist. That's my political philosophy. But I also know that there's great inventiveness in indigenous institutions. There are examples of grassroots leaders in America, like in Kimi Gray public housing leader in Washington in the '80s, was abandoned by her husband at age 23, with five children in welfare. She got off welfare, sent off five kids to college. And then through her leadership organized the residents to take charge of their community. And in 12 years sent 600 kids off to college, eliminating teen pregnancy in that community. And so there have been other islands of excellence where people, grassroots leaders have applied all values to a new vision and a new reality and provided an alternative to that structure that has produced the transformation of these communities. We need to look at what are these islands of excellence, these social entrepreneurs. We need to look at the capacity of people to regenerate themselves and their communities. There are all kinds of examples that we have found at the Woodson Center around the nation, where we... If we say that 70% of the families are raising children with dysfunctional, it means 30% are not. How many studies have gone into the homes of the 30% to find out how are people achieving against the odds? And what is it that we can do to expand and build on what the 30%, And so they can expand it through the 70%? It just takes some imagination, but you have to believe that development is possible in order for you to invest in it.

Peter Robinson: Ian education, gotta be education right for you?

Ian Rowe: Well, what's interesting is that more success in education actually relies very heavily on more success and strong families and strong faith commitments. And when you--

Peter Robinson: Wait, wait. Say that. How is that the case?

Ian Rowe: So when you ask the question, how do we revitalize particularly around faith? One of the things is to realize there are pockets as Bob is mentioning that these islands of excellence, where there are already strong faith communities embracing schools. So in the heart of the south Bronx, where I've run, we have relationships with churches where we have mentoring relationships, reading tutors who are adopting schools and building the connection, which is first just based on reading and improving math outcomes, but also starts to become a pathway that young people start to see value in developing a faith commitment within their own lives. To Glenn's point. There is no top down, suddenly we're just going to have a much broader engagement in faith. However, we should recognize the power of what already exists and create bonds between the institutions that right now are so fractured.

Peter Robinson: So may I ask, it occurs to me, the three of you are tremendously accomplished, but you're also educated. Undergrad MIT is where you got your doctorate, as I recall. And your undergrad degree is?

Glenn Loury: Northwestern Uni.

Peter Robinson: Northwestern and MIT, Chaney and Penn and Cornell and Harvard. So how did the three of you do it? If this isn't too personal, if you go back to your family, you were encouraged by your families? You got excellent education when you were a little kid? How did it happen for the three of you? Let's start with you, Bob.

Robert Woodson: Well, first of all, my dad died when I was nine, leaving my mother with a fifth grade education and five kids to raise. And so there was no encouragement on that.

Peter Robinson: She was just trying to hold on.

Robert Woodson: She was just trying to hold on. And my friends were a year older than me. And so they graduated. So I dropped outta high school and went into the military, the Air Force and entered a space program . And I got trained and I finished my GED in the service and went to University of Miami when I couldn't walk on the campus 'cause of segregation. But they had extension courses on the base, but I decided when I'd looked at how bad blacks are being treated in the south, and I said their education is no better than mine. If I wanted respect, I have to go. So from that day on, I worked hard, graduated, got my GED, came out and went to, blessed to go to Chaney, had a loving professor who took these 13 veterans under his wing. We went all... We went 12 hours a semester and then we went all summer so we could finish on time. And so it was a grind for me because I had not read a book cover to cover until I went to college. And so it meant I had to go into the library to make up background reading, but then I was able to go, thank God, it didn't have affirmative action, Glenn. And they sent me right to University of Penn. But I went to a black college who took me in, and then prepared me to compete at Penn. And I did very well at the graduate school.

Peter Robinson: So for you, it was--

Robert Woodson: I was the first person in my family to finish college.

Peter Robinson: You spotted it as the way out.

Robert Woodson: Right. Of being disrespected, that I saw blacks were being mistreated in the south. I saw this. I didn't want to be treated like that, but I knew that I had to prepare myself if I didn't want to be treated like that. So I thought my destiny was in my own hands. And so that's what I did.

Peter Robinson: And what's your story with regard to education?

Robert Woodson: I came up through public education in Chicago in the mid '60s. It was not half bad. I got a decent high school education. I was a very young father, I dropped out of college, went back to a community college for a couple of years. Got discovered by a math teacher there and recommended for a scholarship at Northwestern, which is what got me to Evanston, where I finished the last two years of my college education. I did very well and had options and ended up at MIT. But my inspiration came from my father who was a self-made man, very hardworking, finished college and law school at night, was a certified public accountant. Ended up with a distinguished career as a manager in the Internal Revenue Service. And even though he in my mom broke up pretty early in my own life, he was a constant presence in my life and a constant source of encouragement and inspiration and cajoling. He wouldn't let me fail.

Peter Robinson: Wow. And Ian, what's your story? I mean, with regard to education, you were squared away enough by the age of what? 18, to head off to Cornell. How did that happen?

Ian Rowe: I was.

Peter Robinson: How did that happen?

Ian Rowe: Well, like with most of us, our parents played a huge role. My parents were married for 48 years before my father passed away. And they were from Jamaica, West Indies. So, they came to the United States in the mid 1960s during a time of, incredible racial turmoil. So they had no... They were under no false solution of the challenges that would face. And I remember my father always used to say in Jamaica, I was a man. I was a man. It wasn't until I came to the United States that I realized that I was a black man. So it was very profound. But even with that, he said, this is still a place where through strong family, strong faith, strong education, our lives can be better. And so I was in New York City public schools, K through 12, I went to Brooklyn Tech High School. And, you know, growing up you... and you know, another thing my parents also, they frankly didn't like the way that they saw other young black men being raised, and the kinds of ideas that they felt they were being exposed to. So I had a very sheltered education K through 12.

Peter Robinson: So of course individual experiences are just that individual experiences. But we've got in two cases out of three, we've got parents who are playing a crucial role. And in the third case, it's just personal heroism. I don't know any other way to describe this man's life. So how is this... I still, how do you... How do we graft you guys? How do we take a DNA sample and spread this around? How is your experience replicable? You were looking at me as though I'm asking the dumbest--

Glenn Loury: No, it's not a dumb question, it's just a hard question, Peter. I think we have to live in the 21st century, which is where we are right now, for my money, the kind of work that Ian is doing, building from the ground schools that can effectively educate young people is one part of the answer to your question.

Peter Robinson: That's a lever we can put.

Glenn Loury: Look at seven in 10 babies born to a black woman in this country are born to a woman without a husband. That's seven in 10. When Bob Woodson was coming along in the 1930s and 1940s, that number was one in 10. I don't know, you know, you can pull on a string and you can unweave a fabric and it will unravel before your eyes, pushing on that string is not gonna put Humpty Dumpty back together again. We got a hard problem here.

Robert Woodson: Well, my response is that what I tried to do is write down, I've a book called this is commercial, "Lessons From the Least of These" where identify what are the 10 principles that one can follow to know how to find people like this and how to promote them. But also, I think on what I'm inspired about capitalism is that 60% of Apple's income comes from something that didn't exist 8 years ago. So there's ingenu... So I look for that same spark of entrepreneurship in the social marketplace too. So I hope to be able to point people through my example, and to look among the people suffering the problem, to look for a spark of innovation, some system that people can employ that will take what seems to be the salvation of a few and expand it to the many. So, I rely and my trust is in the inventiveness of people.

Peter Robinson: Can I go back to a point all three of you have made and that Tom Sowell makes repeatedly, and that is that for African Americans, that first century, from the end of slavery to the civil rights. And it's pretty much an even century, the civil war ends in 1865. The big civil rights legislation comes in 64 and 65. Well, let me just quote Tom Sowell. This is Tom writing in 2015, "Despite the grand myth that black economic progress began with the passage of the civil rights laws, the cold fact is that the poverty rate among blacks fell from 87% in 1940 to 47% by 1960. And that was before any of these programs began. Nearly 100 years as the supposed legacy of slavery found most black children raised in two parent families, almost 80% in 1960, but 30 years after the liberal welfare state found the great majority of black children being raised by a single parent, two thirds or so in by 1990." And so this is just staggering. There is a century of African American history.

Ian Rowe: Growth and prosperity prosper.

Peter Robinson: It is staggering from slavery to educational attainment, climbing out of poverty, intact families and nobody knows about it.

Ian Rowe: Did you read about it? Did you read about it in the 1619 Project?

Peter Robinson: I did not.

Robert Woodson: We have it in the 1776. That's why we---

Peter Robinson: So can I ask just first, why has this century of history

Robert Woodson: Been ignored?

Peter Robinson: Been submerged? And I'm asking--

Glenn Loury: That is politically inconvenient to focus on it. I mean, there's no surprise here.

Peter Robinson: This is politics.

Glenn Loury: Where did... Where did we start in 1865? You had 4 million people who had been enslaved person, suddenly emancipated and made citizens. They were largely illiterate. They were largely landless. Some had skills because it was in the slave owners interest to have his property with skills, but most did not. So the saga of African American History in post emancipation is largely a saga of victory over the conditions in which they were left at the onset of their liberation.

Peter Robinson: And I'm maintained that properly understood, it is one of the great epics in all of American history.

Robert Woodson: It really is. It is, but there is a dynamic of this that is in order to qualify to have the civil rights law applied to blacks. 'Cause originally civil rights laws have nothing to do with blacks when the federal government intervening in the state, it was because of the slaughterhouse cases in Louisiana, where the government came in, 'cause they were afraid of destroying the food supply. What the black leadership concluded in order to get them to quality, we have to demonstrate that segregation is harmful to us. And so we ceased publishing, the black colleges used to publish journals highlighting the success of businesses. So we had to demonstrate to the government that we were harmed by it. And so therefore we ceased publishing journals about our success. So that was one unintended consequence of winning civil rights laws.

Peter Robinson: So it's--

Robert Woodson: That was.

Peter Robinson: You see, I kind of hold you responsible.

Glenn Loury: How's that?

Peter Robinson: Because you're a full professor, a chaired professor at a fancy pants university, and it should be the duty. One of the first duties of fancy pants universities like Brown to instruct every kid, not just black kids, every kid.

Robert Woodson: That's what I wrote.

Peter Robinson: In that epic that century of progress. Shouldn't it? Shouldn't that be, how can we expect African Americans or Americans of any color to understand the true history of this nation and the true... That those income gaps don't need to be there? That they didn't used to be there? And that is... There is no fact about American existence more important than the facts of that century of achievement. Am I not making sense?

Glenn Loury: Well, you're preaching to the choir if you're asking me and I do try to give this message in my courses. But I'm not the only guy. And there is a counter narrative and that narrative wants to focus for example, on the wealth gap. It wants to nurse and nourish a sense of grievance and victimization. It points to the history of... And the very undeniable history of racism and discrimination, which extended well beyond the end of the civil war. It points to that and it builds the story. The story that you see in the 1619 Project, A story that I think had merit in 1950, but story that I think is an anachronism in 2022.

Robert Woodson: It's also perverse incentives. We've spent 22 trillion in the last 60 years with 70 cents of it goes not to the poor, but those who served the poor. So we've created a commodity out of poor people, and a lot of black professionals are in the sector that is delivering those services.

Peter Robinson: Right. As Tom Sowell said, these the anti-poverty programs definitely do eliminate poverty among the bureaucratic.

Robert Woodson: Yes.

Peter Robinson: So what do you make of this? This submerged or forgotten century of progress?

Ian Rowe: Well, Nikole Hannah-Jones, the primary author of the 1619 Project wrote an 8,000 word essay in a follow up in the New York Times magazine. And it's called "What We are Owed". And in this essay, she waxes eloquently and even says, "There is nothing a black person can do." Doesn't matter if you get married, doesn't matter if you get college educated, doesn't matter if you buy a home, doesn't matter if you save, none of those things quote "Can overcome 400 years of racialized plundering." So she completely ignores the fact that A in her own life, she's done all of those things to lead a life of prosperity, but she ignores that full 100 year, not only the 100 year history, but contemporary. Because when you do look at the racial wealth gap, yes, there is a gap based on 2019 data of about $160,000. The median wealth of the average white family is about $160,000 more than the median wealth of the average black family. But take into account just two other factors, family structure and education, the median wealth of the average married college educated black family is about $160,000 more than the median wealth of an average single parent white family. So perhaps there are factors beyond just race that if we were being honest in this conversation, we could collectively tackle and come up with solutions. But to Glenn's point, if the narrative for which you obtain and maintain power is based on this idea of a victimized community, then you have a perverse incentive to ignore all of this. And just say that America is inherently racist and oppressive.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Now we're talking about politics and incentives and using the... Fine, the three of you say, get an education, get married and stay married, work hard. And there's a political party in this country that for all its flaws, fundamentally believes all three of those things. Now listen to this, the proportion of African Americans who voted for Richard Nixon in 1960, 32%, the proportion who voted for Donald Trump, 8%, the first time around.

Peter Robinson: And then, what I show here is 12% the second time. In other words, even Donald Trump who drives all kinds of people crazy, but he made a concerted effort to reach out to the African American community. There's this marvel... I thought it was strike. I shouldn't say marvels, but striking moment during the first presidential campaign, when he visits a church in Harlem, and he says, "What have you got to lose? What have you got to lose?"

Ian Rowe: Yes.

Peter Robinson: So we still have African Americans voting pretty monolithically for the party of what do we call it? Victimization? Well, all the things that the three of you have said, do African Americans harm. How can this be? Glenn.

Glenn Loury: Well, the Democrats sold the bill of goods to the black community, that they were the party of civil rights and that the expanding welfare state was gonna take care of everybody. And the Republicans haven't done such a good job at disabusing people of that idea. I'm not a political operative here. I'm not sure about the mechanics of how to win votes, but I think that there are two things going on. One of them has to do with the effectiveness of the Democrats. I almost said demagoguery around racial issues. I mean, what does Joe Biden say? They're gonna put y'all back in chains. He says, if you want to have a voter ID shown before you cast the ballot in Georgia, that's Jim Crow, 2.0, although all this is about making black people afraid that racists are gonna come in the middle of the night and carry yourself. But the Republicans haven't done such a good job. We'll see what happens in the coming cycles of framing their approach and asking for the votes of African Americans in a way that disabuses us of this view that only the Democrats can lead us to the promised land.

Robert Woodson: Republicans got the old fashioned way they earned it. The Achilles heel has been raced in poverty. Bill Bennett said that when liberals see poor people and black people, they see a sea of victims and Republicans see aliens. But what they have done, their messaging has been horrible, but--

Peter Robinson: The Republican message.

Robert Woodson: Yeah. But when you look at Dick Riordan, who became the first Republican mayor of Los Angeles in 35 years is because he understood that you have to plant charitably and then you can harvest politically. He went into East LA two years before he declared and talked to the local people and helped and built an institution there. And then when he declared, he received the support of people. Same with Steve Goldsmith in Indianapolis who planted charitably, but also looked directed the privatization of public services and contracted with churches so that people... So he transferred wealth and whatnot. And he got the reward. DeSantis was elected by 32,000 votes, 100,000 blacks voted for him, even though they brought--

Peter Robinson: Because it's school choice.

Robert Woodson: Yeah. School choice, even though he brought in Oprah and Obama. So black America in the 2018 gubernatorial race,

Peter Robinson: Wait a minute. So let's just repeat that. Ron DeSantis got elected governor of Florida by a very narrow margin. He was running against a black man, Andrew Gillum. And Andrew Gillum brought in Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey

Robert Woodson: And Oprah. and the blacks

Peter Robinson: Oprah is even bigger than Barack Obama.

Robert Woodson: Right. And 100,000 blacks voted against Oprah and Obama and voted for DeSantis.

Peter Robinson: And voted for DeSantis. because of school choice.

Robert Woodson: School choice. And that's not--

Peter Robinson: So what about your parents?

Ian Rowe: Well, I was just about to say

Peter Robinson: Do your parents in the Bronx understand that the Democrats are in work closely together with the teacher's union, and the teacher's union does not wish you well?

Ian Rowe: So in our schools, we had about 2000 students, almost all low income, almost all black and Hispanic. We had nearly 5,000 families on our wait list. If I were to venture a guess of that total 7,000, or families, so maybe 10,000 or more adults or more, I'd say 90% were Democrats and voted Democrat in New York City. But you take away the power to choose a great school for their child in a district, in which only 2% of kids historically were graduating from high school, ready for college. What I find interesting about this discussion, there is this disconnect between a voting pattern and actually the issues that really resonate with the very people that we're talking about. So it's not surprising that what you see in Florida was this huge realization. Like, wait a minute, that guy actually doesn't stand for what really matters to me. And for most low income folks of any race. That has to do with the quality of education for your child. And if there were smart people in the conservative Republican movement,

Peter Robinson: They would do.

Robert Woodson: They they'd recognize.

Peter Robinson: They'd be going into black neighborhoods and saying, "Look, I'm gonna give your kids a chance."

Robert Woodson: Exactly.

Peter Robinson: It's as simple as that.

Glenn Loury: What have you got to lose?

Peter Robinson: What have you got lose?

Ian Rowe: Well, really what have you got to gain.

Peter Robinson: Everything.

Ian Rowe: Which is the ability to send your school, send your child to the school of choice.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Couple of last questions. Let me give you two quotations. Here's Frederick Douglass in 1865, "Everybody has asked the question, what shall we do with the Negro? I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us. Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us. All I ask is, give the Negro a chance to stand on his own legs and let him alone."

Robert Woodson: That's true.

Peter Robinson: President Barack Obama in 2014, "Because of the civil rights movement, because of the law President Johnson signed, new doors of opportunity and education swung open for everybody, not all at once, but they swung open. It's perhaps easy to conclude that there are limits to change and we'd be better off if we roll back big chunks of LBJs legacy, or at least if we don't put too much of our hope in our government. I reject such thinking." Bob, who are you with? Barack Obama or Frederick Douglass?

Robert Woodson: Frederick Douglass. That's an easy one. And I think Booker T Washington said there are classes of Negroes who profit and benefit from our grievance. If we lose our grievance, they lose their income.

Peter Robinson: But isn't Frederick Douglass, this is just too stark. "Leave the Negro alone." It sounds hard.

Glenn Loury: These guys are talking at completely different times. Douglass in the late 19th century, in the late 1800s and Obama in the 21st century. There's something called the welfare state. It's contentious. This quite independently of race. Obama is saying food stamps are a good thing. He's saying Medicaid is a good thing. He's saying aid to families who don't have enough money to put a roofer ahead and feed their kids is a good thing. So Frederick Douglass wasn't confronted with that question. Now, I'm not saying that Obama was right in every respect. What I'm saying is that there are two different things going on. What does the Negro need to do? Black people I speak into old language to stand up straight with our shoulders back, raise our children and get ahead in life. That's one question. Another question related but distinct is how will we Americans organize our social compact with one another, I'm talking about healthcare, et cetera. So is to create a decent society on which Democrats and Republicans have different ideas.

Ian Rowe: And the one thing I'd say, I would definitely lean to the Frederick Douglass quote, but again, to Glenn's point, context matters. 'Cause when he says, "Leave us alone." At that time, he could rely on the fact that black communities had strong families, strong married two parent households. He could rely on the fact that of the church, the faith commitment. So when he was saying, "Leave us alone," I presume he was also saying we have the institutional support--

Robert Woodson: That's true.

Ian Rowe: That allows us to lead a self-determined life. So the reason it sounds harsh today as someone who run schools, I wouldn't say to a kid, "Just leave us alone." Because I can't count on all of the important mediating institutions, which are so crucial for a young person's development. So I would make a slight amendment to revitalize the family, faith-based organizations, educational school choice, which then based on those supports, leave us alone once we've got those.

Peter Robinson: Once you've got that.

Ian Rowe: Yes.

Peter Robinson: All right. Last question here. Imagine two students, one white and one black, let's say they're college kids. They're that age, 18 to early 20s. And they're both in a college that responded to the BLM Movement last year. The way that all the colleges responded with listening sessions, new committees to examine institutionalized racism on and on and on, you know, the whole scene. And both students, they're kids, they're idealistic, they want to help. They wanna know what they can do. What do you tell the white kid?

Ian Rowe: Wait, what they can do to accomplish what?

Peter Robinson: To help, let's put it this way. To help eliminate those gaps. Let's just keep... Let's just make it quite definite. Those gaps with which we can, educational gaps, the disparities. Disparities in education, disparities in income, broadly speaking to improve the life of that segment of African Americans who seem in all kinds of ways to have been left behind. So what do you tell them? Do you tell them the same thing? Do you say a different thing to the white kid and the black kid? How do you answer that question?

Ian Rowe: Well, I certainly wouldn't want to create the impression that the black kid is dependent upon the white kid's benevolence to suddenly transform his or her situation. I'd much more focus on the black student and talk about the tools that he has within his quiver to be successful and not feel in a sense that he's dependent on whatever it is that white student chooses to do, 'cause by the way that white student could be failing and needing to focus on his studies, and this black student could be quite exceptional. And so I wouldn't even make the assumption that it's this black student who's the one in need of some kind of assistance. And again, I think these narratives are the things that sometimes get in the way of our ability to identify the assets that each person has. Last quote that De Tocqueville when he was observing America, he wrote, "The greatness of America lies not in that it's more enlightened than any other nation, but in its ability to repair her faults." And the reason I love that it talks about this sense of self betterment and self-development that exists within our country that I want to ensure every young person knows that they have those same tools of self betterment and self development.

Peter Robinson: You know what, let, me readjust the question. Ian just did such a beautiful job of answering the question I asked and answering the question I didn't ask, but that I'm about to ask. Nikole Hannah-Jones on the 1619 Project says in effect to kids, "If you grasp nothing else about this country, grasp that the United States of America was conceived in racism." What do you say? If you grasp nothing else about the United States of America to a kid in a sentence or two, what must you grasp?

Glenn Loury: That was conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all people are created equal. That it is a great nation. That it is the most powerful force for human liberty in the history of the world. I mean, what is the United States actually? I mean, we could go into the details. Of course there was slavery, but there was also emancipation, et cetera. We defeated fascism on two oceans in the middle of the 20th century, we stood down a nuclear armed Soviet Union on behalf of a free world. We have the greatest engine for prosperity in the history of humankind. Anything is possible in this country. That's why people vote with their feet to come here from every corner of the world. The world is moving fast I would say to Nikole Hannah-Jones and anybody else who's listening. You can have your head in the 19th century if you want to, but the Chinese are coming.

Peter Robinson: Bob Woodson. What would you say to a kid about this country?

Ian Rowe: I would say that When you look back about how blacks have fought in every war to protect this country, and not a single one that's been guilty of treason it's because we believe as Glenn said in the virtues and promise of this country. And how can you expect that a person to go and risk their lives to defend this country if you say that the country of your origin is racist, and therefore hostile to your future? But again, what I said before that young people are motivated to improve themselves when you show them victories that are possible. When you relate to him to all of the victories of the people in the black community who built hospitals and colleges and hotels. I would just show them what we were able to do by embracing the principles of our founders.

Peter Robinson: Glenn Loury, Bob Woodson, Ian Rowe, thank you.

Glenn Loury: Thank you.

Ian Rowe: Thank you.

Peter Robinson: From the Old Parkland Conference in Dallas on behalf of Uncommon Knowledge, the Hoover Institution, and Fox Nation, I'm Peter Robinson.