- Economics

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Budget & Spending

- Health Care

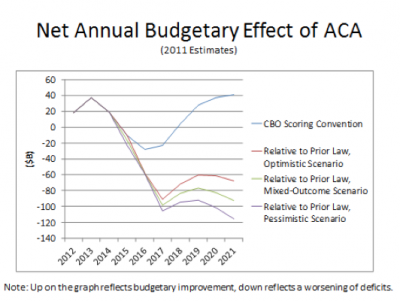

Throughout 2009 and early 2010, supporters of the then-pending Affordable Care Act (ACA) argued that health-care reform was necessary to repair the federal government’s untenable fiscal outlook. More than any other factor, it was said, health-care cost inflation was the driving force behind massive projected federal deficits, and comprehensive reforms were required to cure the problem. Unfortunately, when enacted, the ACA worsened federal finances rather than improved them.

The legislation as originally passed would have added at least $340 billion to federal deficits in its first ten years (and over $1.15 trillion to federal spending) and far more in each subsequent decade. This past summer, the Supreme Court threw a wild card into the fiscal picture, striking down the federal government’s power to compel the states to participate in the ACA’s vast Medicaid expansion, while essentially leaving the rest of the law standing.

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

As a result, depending on policy decisions yet to be finalized by elected officials at all levels of government, the ACA could ultimately prove either far more expensive—or significantly less so—than originally estimated.

The ACA and America’s Fiscal Future

The ACA’s worsening of the federal fiscal outlook is unambiguous but has been poorly understood because of the scorekeeping rules under which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) operates. Rather than evaluate the effect of the ACA’s literal change in law, as is done with many other areas of the budget, CBO is directed to treat changes affecting Medicare differently. To fully understand this requires some familiarity with the basics of Medicare financing.

Medicare (like Social Security) is only authorized to make benefit payments when there is a positive balance in its trust funds. Lawmakers are on notice that if the Social Security or Medicare Hospital Insurance trust funds face depletion, action must be taken either to increase revenues or slow the growth of payments to avoid a sudden interruption in benefits.

CBO is instructed to disregard this restriction on Social Security and Medicare financing whenever it scores legislation. Instead, CBO is directed to assume that Social Security and Medicare will make full scheduled benefit payments in perpetuity, even though the programs lack the financial resources and statutory authority to do so. This is important not only because this assumption differs markedly from actual law (as CBO publications are careful to acknowledge), but also because it is without historical precedent.

Though lawmakers’ management of Social Security and Medicare has exhibited flaws, historically trust fund financing limitations have been taken seriously. These restrictions are the reasons behind the substantial benefit restraints and tax increases of the 1983 Social Security amendments, none of which would have been obligatory if Social Security were permitted to spend in excess of its trust fund resources as CBO is compelled to assume. Instructing CBO to ignore these critical statutory restrictions distorts its scorekeeping findings.

In sum, the scorekeeping baseline used to show a positive fiscal effect for the ACA reflects neither actual law nor historical practice. This hypothetical scenario, involving as it does perpetual overrides of Social Security and Medicare financing restrictions, would be untenably expensive. Yet it was only in comparison with this extreme and extra-legal scenario that the ACA was found to slightly reduce projected federal deficits. In comparison with actual prior law, the legislation greatly worsened the fiscal outlook.

Another way of understanding this is to acknowledge that well before the ACA was passed, the federal government had a statutory obligation to keep the books of the Medicare Hospital Insurance program balanced in some way. Either they would be balanced by prudential legislative action to align the program’s payment and benefit schedules, or, in the worst-case scenario, by an interruption of payments at the point of trust fund depletion. One need not believe that Congress would have ever have allowed the Medicare HI trust fund to be depleted to recognize that long prior to the ACA, there were pre-existing statutory constraints upon future Medicare spending.

That the ACA has worsened the government’s fiscal position is readily seen by surveying its various provisions. Some ACA provisions reduced the growth of future Medicare provider payments. These restraints were enacted pursuant to the longstanding obligation to maintain Medicare HI solvency as described above. There was no prior statutory obligation, however, to enact the ACA’s massive expansion of federally subsidized health-care coverage. The ACA, then, coupled previously-required cost constraints with wholly new spending. This combination worsened the government’s fiscal imbalance.

Another way of quickly understanding this is to note that, like Social Security, the Medicare HI program is permitted to spend whatever revenues it generates. If Medicare HI taxes are raised, more Medicare payments are permitted. Thus, those same taxes cannot also be used to finance a new health entitlement, as the ACA attempted to do, without in effect spending the same money twice and thereby adding to the federal deficit.

The savings provisions of the ACA are insufficient to both finance an extension of Medicare solvency and to fund a massive new health entitlement. So even if the law’s savings provisions all worked as originally envisioned, the ACA would still add at least $340 billion to federal deficits over its first ten years. Even this outcome would require that lawmakers allow many of its provisions to inflict a steadily higher toll on taxpayers, providers, and beneficiaries over time. If instead Congress re-indexes these provisions in keeping with historical precedent, the deficit increase under this more pessimistic scenario would be over $500 billion in the first decade alone.

The Supreme Court Changes the Calculus

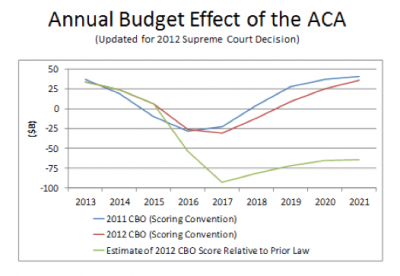

The ACA’s aggressive Medicaid expansion is a significant contributor to the law’s total costs. But this past summer, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not compel states to participate in that expansion. The effect of this decision on the ACA’s finances is complex; it could yet worsen the financial impact of the ACA, or it could mitigate it.

The CBO subsequently reassessed the ACA in light of the Supreme Court ruling. Previously CBO had assumed full state participation in the Medicaid expansion, increasing program enrollment by 17 million by 2022. After the Court’s decision, CBO lowered this estimate by roughly one-third, meaning that 6 million potentially eligible individuals would not be covered under Medicaid. CBO’s updated financial evaluation was better in some respects, worse in others:

—CBO projected that of the 6 million no longer expected to be covered under Medicaid, 3 million would remain uninsured altogether. This would reduce projected federal expenditures.

—CBO projected that the other 3 million would instead be insured under the ACA’s new health insurance exchanges. This would increase costs because the federal government is expected to pay more to cover these individuals under the exchanges than it would have through Medicaid.

Understanding the relationship between Medicaid and the ACA’s new health insurance exchanges is integral to appreciating the potential financial effect of the Supreme Court decision. The ACA was designed to require states to cover individuals with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL)—effectively 138 percent because of a 5 percent income exclusion—under Medicaid. At the same time, the law created exchanges for the purchase of health insurance coverage, available only to those not insured by Medicaid. Also established were substantial federal subsidies for exchange participants with incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the FPL.

Thus if states now choose to leave individuals with incomes between 100 percent and 138 percent of the FPL uninsured by Medicaid, they will become eligible for the new exchange subsidies. Importantly, the degree of government assistance these individuals would receive in the exchanges would generally be greater than under Medicaid. CBO projected that the average federal subsidy for individuals in this income range would be over $9,000 a year, whereas the total annual value of their Medicaid coverage would be less than $7,000. This produces a strong disincentive for states to cover such adults under Medicaid. Declining would not only limit states’ future financial exposure, but also enable these citizens to receive more generous insurance coverage financed entirely by the federal government.

CBO’s re-estimate of the legislation showed slightly lowered projected costs for the law’s coverage expansion (due to the 3 million remaining uninsured), but also slightly worsened finances for the law as a whole. The re-estimated law would add over $340 billion to total deficits and roughly $1.2 trillion to total federal spending over the next ten years.

The fiscal uncertainties associated with the ACA had meanwhile clearly worsened. If all states chose to expand Medicaid coverage to 100 percent of the FPL, with those above 100 percent receiving more generous federal subsidies through the exchanges, total costs might be substantially higher.

What Next?

To prevent the ACA from considerably worsening federal deficits would require eliminating the equivalent of roughly two-thirds of the projected cost of its health exchange subsidies. More ambitiously, to prevent the ACA from increasing federal spending would require even greater corrections—such as eliminating the entirety of the subsidies’ costs as well as roughly two-thirds of its Medicaid expansion. To achieve either objective, it is essential that the constraints be enacted before the expansion’s scheduled start year of 2014. History shows that it is very difficult to constrain the growing cost of a new federal entitlement once benefits are being drawn.

State governors, cognizant of the incentives described in this article, wrote earlier this year to ask HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius for clarification on whether the ACA’s generous federal funding match rate would apply to a more limited expansion of Medicaid. Secretary Sebelius recently replied that it would not. Though HHS’s decision was apparently motivated to coax states to expand fully to 138 percent of the FPL as the ACA specified, the actual effect of the “all or nothing” choice is likely to be that many states will now choose not to expand Medicaid at all. Evidence for this lies in the fact that historically few states had sought waivers to fully cover this population at pre-ACA federal match levels. If this expectation is borne out, this would somewhat lower the ACA’s projected costs.

A number of states have already announced that they will not expand Medicaid or set up health exchanges. This should not by itself be expected to fix the fiscal problems associated with the ACA. The ACA empowers the federal government to establish exchanges where the states decline to do so. Though there is an ongoing legal dispute over whether the federal subsidies are triggered where the federal government operates the exchanges, the subsidies, where they do exist, are expected to be more expensive per person than the Medicaid coverage would have been.

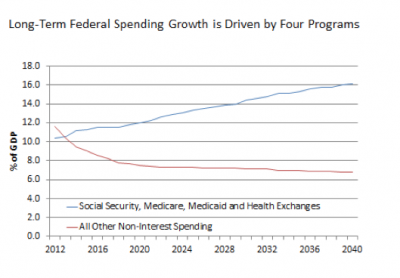

The ACA’s adverse financial impact can thus only be fully corrected if the law’s health exchange subsidies are scaled back significantly. Projected federal fiscal strains are driven entirely by projected growth in four federal programs alone—Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and the new health exchange subsidies. Repairs to the federal fiscal outlook cannot be credible without tackling the exchanges’ costs. Adding to the urgency of this imperative is that without subsidy reductions, states face the aforementioned incentives to shift individuals from Medicaid coverage to the new exchanges and drive the ACA’s costs still higher.

Elected officials at all levels of government should act to lessen the fiscal damage wrought by the ACA. Federal legislators should focus on scaling back the direct costs of the law, starting with its health exchange subsidies. States can also lessen costs by declining to expand Medicaid coverage unless they are given ample flexibility to improve the program’s cost-effectiveness. Such restraint will also hold down federal expenditures because the federal government finances the majority of Medicaid costs.

The worthy goal of expanding health insurance coverage was one of the motivations for passing the ACA. The ACA however lacks sufficient savings provisions to finance such a coverage expansion without severely worsening the fiscal outlook. A fiscally responsible coverage expansion will continue to elude us unless state and federal lawmakers do everything yet possible to reduce the projected cost of the ACA’s provisions before they become fully effective in 2014.