- History

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

Foreign policy suddenly took center stage in the presidential campaign when the twelfth anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks was marked in the Middle East with violent protests against U.S. embassies in 20 countries, including an attack on our consulate in Benghazi that resulted in the death of diplomat Christopher Stevens. This violence was allegedly sparked by a crude Internet video insulting Mohammed and Islam. A few weeks later, President Obama addressed the United Nations in an attempt to placate enraged Muslims, defend the First Amendment, and confirm his commitment to the regional revolutions against autocrats dubbed the “Arab Spring.”

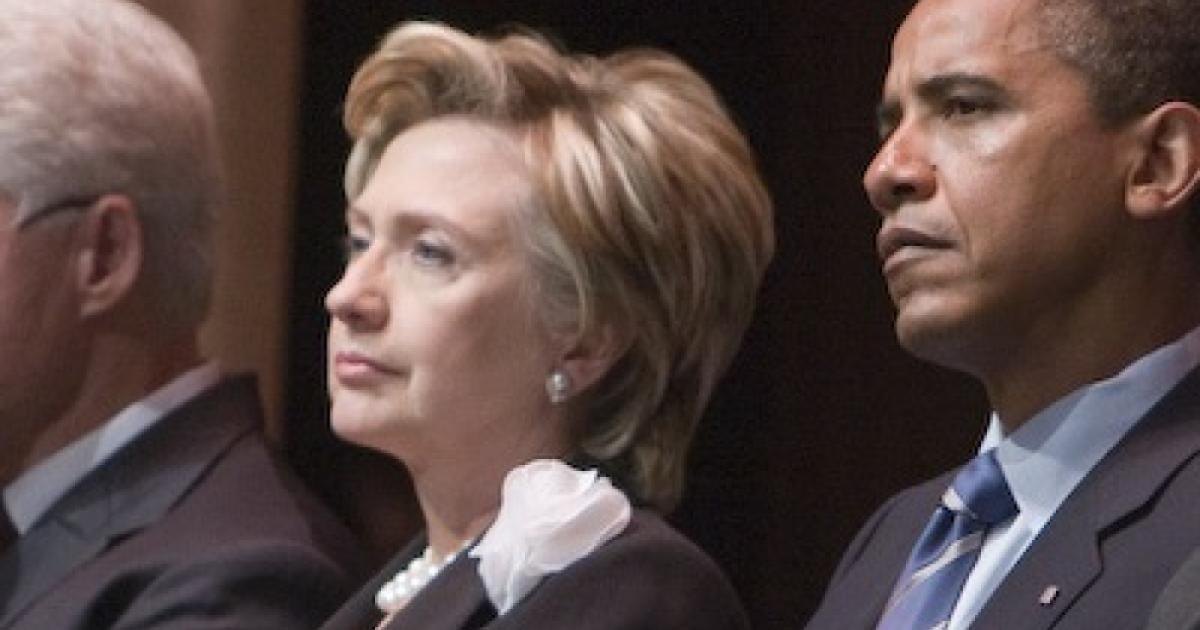

Photo credit: Barack Obama via flickr

Yet the President’s speech repeated a mistake that our foreign policy establishment under both political parties has been making for nearly a 100 years: the failure of imagination that historian Robert Conquest identified as diplomacy’s besetting sin. “We are still faced with the absolutely crucial problem of making the intellectual and imaginative effort not to project our ideas of common sense or natural motivation onto the products of totally different cultures,” Conquest wrote in 2000:

The central point is less that people misunderstand other people, or that cultures misunderstand other cultures, than that they have no notion that this may be the case. They assume that the light of their own parochial common sense is enough. And they frame policies based on illusions. Yet how profound is this difference between political psychologies and between the motivations of different political traditions, and how deep-set and how persistent these attitudes are!

The “illusion” that has resulted from our own failure to imagine what motivates hundreds of millions of Muslims is the notion that political freedom and democracy are the highest goods desired by all humans everywhere. Thus we must help the people who lack these boons acquire them in order to eliminate the political oppression and economic stagnation that feed terrorism and violence.

Yet this belief ignores the specific historical and cultural contexts of democracy’s creation and expansion. As diplomat George Kennan wrote in 1975, “Democracy has . . . a relatively narrow base in time and space; and the evidence has yet to be produced that it is the natural form of rule for people outside those narrow perimeters.”

The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson

This belief about the universal appeal of democracy, however, has a long history in America, and was most famously articulated by Woodrow Wilson. In his 1917 speech asking Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, Wilson said that the purpose of the war was “to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power,” for “peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations.”

Thus “the world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty.” Americans “are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.” Implicit in Wilson’s remarks is the idea that freedom, democracy, and peace are the default political goals for the whole world.

President George H.W. Bush sounded the Wilsonian note in his 1991 State of the Union address delivered during the first Gulf War. The fast-approaching disintegration of the Soviet Union seemingly confirmed the triumph of democracy, and the establishment of “a new world order,” Bush said, “where diverse nations are drawn together in common cause to achieve the universal aspirations of mankind––peace and security, freedom, and the rule of law.”

Despite the subsequent bloody global conflicts, civil wars, al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks, and brutal ethnic cleansing in Sudan and the Balkans that marred the Nineties, the democracy dream maintained its potency. President George W. Bush, in the 2002 National Security Strategy, defined the foreign policy of the United States as promoting a “single sustainable model for national success: freedom, democracy, and free enterprise,” for “these values of freedom are right and true for every person, in every society.” Thus the U.S. will strive “to extend the benefits of freedom across the globe. We will actively work to bring the hope of democracy, development, free markets, and free trade to every corner of the world.”

Bush returned to these themes in his January 2005 inaugural speech, in which he linked U.S. security and global peace to the “force of human freedom” and the expansion of democracy: “The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.”

President Obama’s “Realism”

President Obama has touted a more realist foreign policy, one suspicious of democracy promotion and nation-building abroad. “Now is the time to focus on nation-building here at home,” he said in 2011.

But when the revolts broke out in the Middle East, he supported them, albeit selectively. He committed American forces to bombing Libya in order to remove the brutal Muammar Gaddafi, and helped push Egyptian strongman and American ally Hosni Mubarak out of power. Assuming the universal appeal of freedom and democracy, last month on 60 Minutes, the president defended his support of the Arab Spring revolts by saying, “I think it was absolutely the right thing for us to do to align ourselves with democracy [and] universal rights.”

The recent setbacks to the spread of democracy, seen particularly in Egypt, where the illiberal and Islamist Muslim Brotherhood now dominates the government, and, most obviously, in the recent anti-American violence against our embassies across the Muslim world, have not tarnished democracy’s transformative powers, at least according to Obama.

In his remarks at the U.N., Obama reprised the tradition of American idealism stretching back to Woodrow Wilson. He said America supported the various Arab Spring revolts because “we recognized our own beliefs in the aspirations of men and women who took to the streets” and “our support for democracy put us on the side of the people.”

Channeling Bush the second, Obama asserted, “Freedom and self-determination are not unique to one culture. These are not simply American values or Western values––they are universal values.” Obama also endorsed the ability of democracy to change the world: “I am convinced that ultimately government of the people, by the people and for the people is more likely to bring about the stability, prosperity, and individual opportunity that serve as a basis for peace in our world.”

The True Realists

Muslim leaders across the world immediately dismissed Obama’s paean to democracy, seeing it instead as a form of political imperialism. Rejecting the claim of universal human rights, Egypt’s President Mohammad Morsi responded, “We expect from others as they expect from us: That they respect our cultural specificities and religious references and not to seek to impose concepts or cultures that are not acceptable to us or politicize certain issues and use them as a pretext to intervene in the affairs of others.”

Regarding Obama’s call to respect the key democratic right of free expression no matter how insulting the speech is, Morsi retorted, “And the insults hurled on the prophet of Islam, Mohammed, is rejected. We reject this. We cannot accept it. And we will be the opponents of those who do this. We will not allow anyone to do this by word or deed.” Indeed, the same day he spoke those words, an Egyptian blogger––a minority Christian Copt freely expressing his beliefs–– was hauled into court on charges of mocking religion and religious beliefs and rituals.

Other rulers of Muslim countries seconded Morsi’s rejection of our notion of free speech as a human right. Yemen’s President Abed Rabbu Mansour Hadi said, “These behaviors find people who defend them under the justification of the freedom of expression. These people overlook the fact that there should be limits for the freedom of expression, especially if such freedom blasphemes the beliefs of nations and defames their figures.”

President Asif A. Zardari of Pakistan agreed: “The international community must not become silent observers and should criminalize such acts that destroy the peace of the world and endanger world security by misusing freedom of expression.” About the same time he spoke those words, the Federal Minister for Railways in Pakistan offered a $100,000 reward for the murder of the person who made the offending Internet video. All these rejections of free speech are consistent with the on-going efforts of Organization of the Islamic Conference since 1999 to enshrine Islamic blasphemy prohibitions into international law.

Traditional Muslims have a much different view of human rights than we, as can be seen in the Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam, whose Article 24 reads, “All the rights and freedoms stipulated in this Declaration are subject to the Islamic Shari’a.” Given that Shari’a law does not grant equal respect and rights to all religions, limits the rights of women and religious minorities, regards homosexuality, “blasphemy,” and apostasy as capital crimes, and acknowledges no separation of church and state in law, it’s hard to see how such a notion of “human rights” can be considered similar to our own. The fundamental human right in Islam, according to the Cairo Declaration, is the right to live as a pious Muslim, to not have anything or anyone interfere with living as a pious Muslim, and to have nothing block or impede anybody from hearing the “call” to convert to Islam.

The Consequences of Failed U.S. Foreign Policy

The consequences of our failure to see the world through Muslim eyes are evident throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Contrary to President Obama’s statement on 60 Minutes that “over the long term we are more likely to get a Middle East and North Africa that is more peaceful, more prosperous and more aligned with…our interests,” hatred of America has increased over the last four years even as our influence has diminished, and the region is heading toward more violence and more assaults on human rights.

In Libya, a weak central government shares power with heavily armed militant Islamist bands of the sort that killed our ambassador. Islamists have taken over northern Mali and are applying Shari’a law, including punishments like stoning, amputation, and public beatings. The Islamist Muslim Brothers control Egypt and are likely to create a Shari’a-compliant government, and already are strengthening ties to the terrorist organization Hamas and the regime in Iran. In Jordan, local Muslim Brothers factions are threatening King Hussein with revolution if he doesn’t share power with them. Syria is imploding, the Bashar regime slaughtering its own citizens while al Qaeda-affiliated fighters and other Islamists have infiltrated the resistance.

Despite billions of aid to Pakistan, that country is virulently anti-American and continues to allow the Taliban and other Islamist terrorists find shelter in the regions bordering Afghanistan. Iraq, the beneficiary of American blood and treasure since 2003, is moving closer to Iran, allowing Iranian planes to fly through Iraqi airspace in order to resupply Syria’s Bashar al Assad with weapons. Meanwhile, al Qaeda in Iraq has stepped up terrorist attacks. Afghanistan seems likely to fall once more under the sway of a resurgent Taliban once our troops leave in 2014. Turkey, once a model of an Islamic democratic state, is becoming more and more Islamist, jailing more journalists than any other country in the world. And Iran grimly marches on to the acquisition of nuclear weapons with which it can “wipe Israel off the map,” as President Ahmadinejad has repeatedly threatened.

Meanwhile, the United States has little influence over such events, even as our own national interests, values, and security are put in jeopardy by these developments. Despite over a decade of democracy promotion, genuine democracy appears no closer to becoming a reality in the Middle East.

The reason for this failure is obvious. Democracy is not about free elections. True democracy is liberal democracy—the recognition and protection of inalienable rights belonging to all individuals, the most fundamental one being the right to freedom. These rights and freedoms indeed are goods that all people everywhere may desire, but they are not self-evidently the highest goods that all people everywhere will necessarily desire. People desire many goods—like loyalty to one’s community or clan, fidelity to one’s god or sect, or revenge against one’s enemies—and some of them will trump our goods of freedom, tolerance, peace, and human rights.

The failure to imagine that some humans pursue a plurality of conflicting goods has fostered the grand illusion lying behind the disastrous failure of our policies in the Middle East. No matter who wins in November, if this decades-old illusion continues to define our foreign policy, our ability to shape events in this strategically critical region and protect our interests and security there will continue to be compromised.