- World

- Military

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

Only days after Pearl Harbor, Richard T. Burress was among the thousands of young men crowding into recruiting offices, determined to enlist. A sophomore in college, the Nebraskan had gone to a dance on a Saturday night and awoken the next day to find the nation at war. Told that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, “I said, ‘I always knew they’d hit the Philippines!’ ” he joked recently. A native Nebraskan, “I’d never seen either ocean. I’d never been as far as Chicago.” He would soon travel much farther.

Burress, a Hoover senior fellow, rekindled memories of his wartime service in a recent visit with his old unit, the First Battalion, Twenty-Third Marines. In 1945, he was a fresh second lieutenant leading First Platoon, Baker Company, into battle at Iwo Jima—a “four-day mission” that turned into more than a month of combat. At twenty-one, he was among four hundred replacement officers quickly trained for the assaults on Iwo and Okinawa. Sixty-seven years later, Burress briefly rejoined his unit at Camp Pendleton, where Marines in combat gear cheered and applauded him. His modern counterparts were wrapping up rigorous training for a seven-month deployment to Afghanistan, another distant land with some familiar dangers for an old Marine.

Hoover senior fellow Richard T. Burress meets with Major James Korth, commanding officer of Company B of the First Battalion, Twenty-Third Marine Regiment, as Burress’s old unit wrapped up pre-deployment training at Camp Pendleton. Burress remarked on the major’s height (six feet nine) and urged him to keep his head down.

Burress told the young Marines about an incident that happened on one of his first days on Iwo Jima. He was handed a cup of coffee at the company command post. After the meeting adjourned, he wanted to linger awhile and enjoy the coffee, but at the urgent behest of his platoon sergeant, a veteran of Saipan and Tinian, he dumped it out and set off for his platoon position. Seconds later, a Japanese mortar round slammed into the command post, killing or wounding everyone still there. Don’t bunch up, he reminded the young Marines at Pendleton. Keep as dispersed as possible on the battlefield.

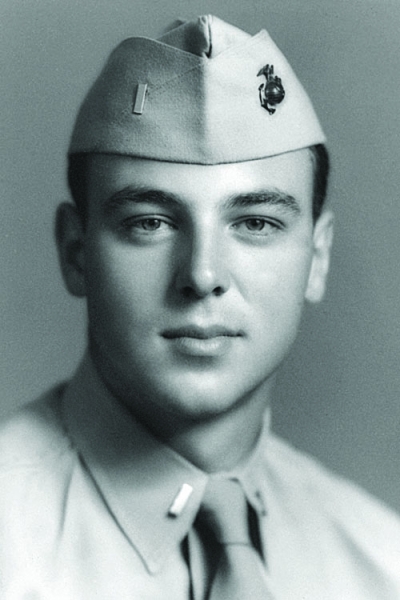

In 1945, Burress was a fresh second lieutenant leading First Platoon, Baker Company, into battle.

Other conditions seemed to have changed over the years. The water on Iwo was always wretched, Burress said, so he would squeeze grapefruit into it to make it palatable. Rations were scarce, too. One day, however, a lance corporal handed him an unfamiliar kind of package with surprisingly decent food. Busily eating, he asked the Marine who had given him the “new rations” where they had come from. “I took them from the colonel’s jeep,” came the reply. Somehow both lance corporal and second lieutenant avoided the wrath of a colonel who bore the nickname “Mad Dog.”

The “boondocks” of Camp Pendleton were certainly familiar to any World War II Marine. “We were in the same hills worrying about the same snakes,” he said of his six-week training on the rugged base after he was commissioned. He watched companies of 1/23 as they engaged in live-fire and scenario-based training for their impending deployment in Operation Enduring Freedom. Towering overhead was a sheer hill known to recruits in basic training as “the Reaper.” As Burress spoke to the troops in Pendleton’s “Combat Town,” mock Afghan villages and rows of mine-resistant vehicles stood in the background.

Burress reminded the Marines that they were making their memories now, and that as Marines they would be viewed differently for the rest of their lives. High expectations were a given. “The bad news,” he said, “is that in sixty years you’re going to look like me. The good news is, you share a special bond as Marines. Your close friendships today will be your close friendships seventy years from now.” He encouraged the Marines to learn and build on their experiences and to consider public service, perhaps including elected office.

“I was impressed with how gung-ho they were,” Burress said back at Stanford. “I told them that the American public was behind them and really proud of them.”