- Economics

- Energy & Environment

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

In the coming days and weeks, standard barometers of the economy will undoubtedly reveal the full extent of the damage wrought by coronavirus. At this point, the question seems to be not whether a recession is coming, but rather how long it will last and how deep the bottom will be.

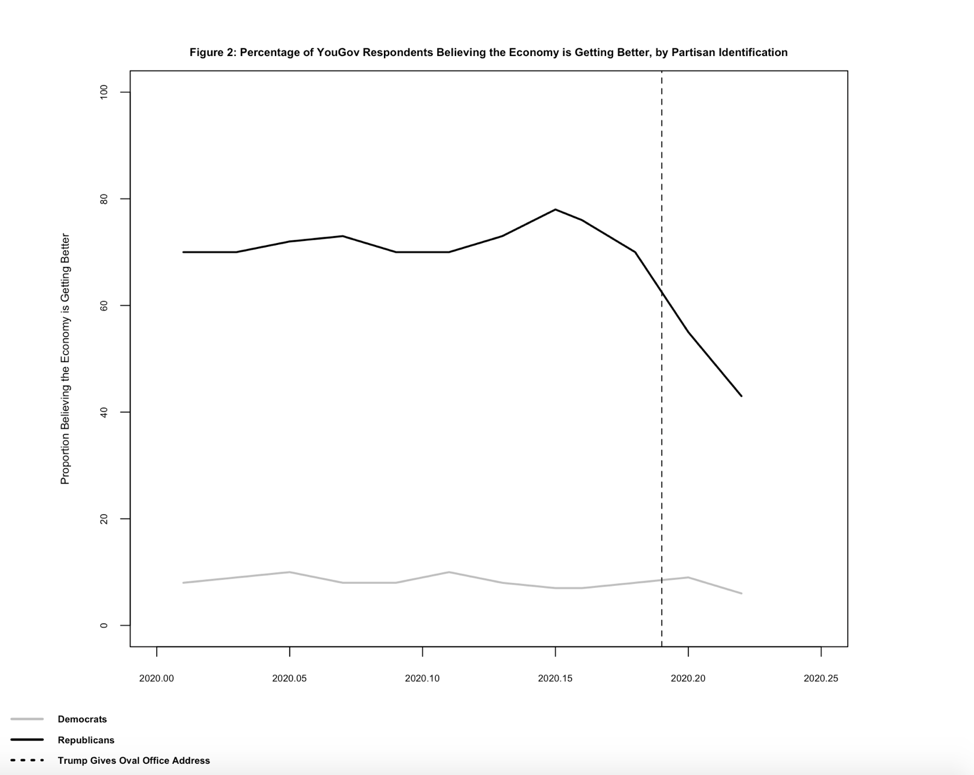

Yet while the Federal Reserve’s actions and a $2 trillion spending deal telegraph the severity of the situation, partisans still do not agree on how dire the situation actually is. As of the March 22-24 YouGov tracking poll, 43% of Republicans continue to believe that the economy is getting better. Only 6% of Democrats believe the same. Independents are in the middle, but closer to the Democrats, with 16% saying the economy is improving.

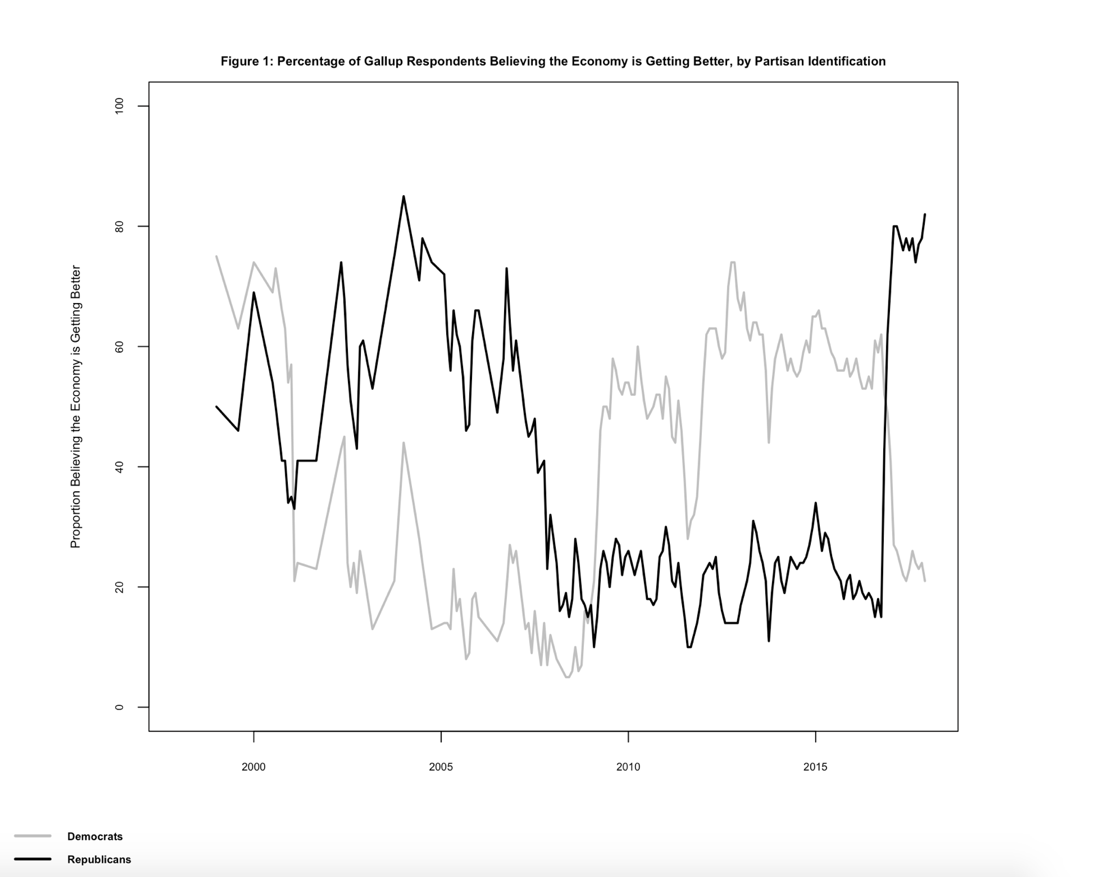

On the surface, these differences might seem surprising. Major news outlets are blaring news of the economy’s demise non-stop, and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin has openly worried that the coming downturn could be worse that the 2008 financial crisis. However, to scholars of American politics, this fits with a consistent pattern of polarized partisan perceptions. Over the last 20 years or so (and particularly over the past 10), partisans’ economic perceptions have consistently tracked partisan control of the White House. As Figure 1 demonstrates, Democrats have generally felt positively about the economy only when a co-partisan controls the White House—the opposite is true of Republicans.

Other research has suggested that these partisan differences in factual perceptions are pervasive and represent sincere differences in beliefs. For example, in a forthcoming paper, political scientists Erik Peterson and Shanto Iyengar assess the degree to which partisans disagreed about the veracity of the following statements (among others):

“The vast majority (over 90%) of climate scientists believe that global warming is an established fact and that it is most likely caused by man-made emissions” (Correct Answer: True)

“Michael Cohen, Donald Trump's personal lawyer, pleaded guilty to fraud and illegal campaign finance charges in August 2018” (Correct Answer: True)

Across these questions, the average difference between Democrats and Republicans was 30 percentage points. Moreover, this gap largely (60-70%) persisted when respondents were offered monetary incentives to answer the questions correctly. This last point is crucial—it shows that most partisan bias in factual perceptions reflects genuine beliefs, rather than insincere attempts to boost the party by “cheerleading.”

Interestingly, however, partisan gaps do not persist under all circumstances. As the economy collapsed in late 2007 and early 2008, Republicans began to sour on the economy (despite George W. Bush occupying the White House). In October 2006, 73% of Republicans surveyed by Gallup reported that the economy was improving (compared to 20% of Democrats); by June 2008, that number has dropped to 15%, barely higher than the 5% of Democrats and 7% of Independents who believed the same. A 53-percentage-point gap was compressed into a 10-point margin.

That precedent suggests that we should expect similar partisan convergence under these circumstances. Last week, 3.3 million Americans filed for unemployment, and even the president admits a recession may be on the horizon. Faced with such unambiguous signs of an economic slowdown, the GOP faithful should have a difficult time maintaining economic optimism. Pessimism might set in particularly quickly if GOP-leaning areas are hit hard by the economic impact of the crisis—a recent New York Times article found that concerns about coronavirus were highest among Republicans in states where the pandemic had already done serious damage.

Regardless, Figure 2 indicates that convergence may be underway. While 70% or more of Republicans believed the economy to be improving for most of this year, that figure declined to 55% two weeks ago and 43% this week. Perhaps not so coincidently, President Trump changed his public rhetoric about the crisis around two weeks ago as well; he shifted from comparing Covid-19 to the seasonal flu to giving a primetime address about the subject in the Oval Office. Whether or not the new messaging strategy is itself responsible for the change, the fact remains that the differences between Democratic and Republican economic perceptions have been nearly halved.

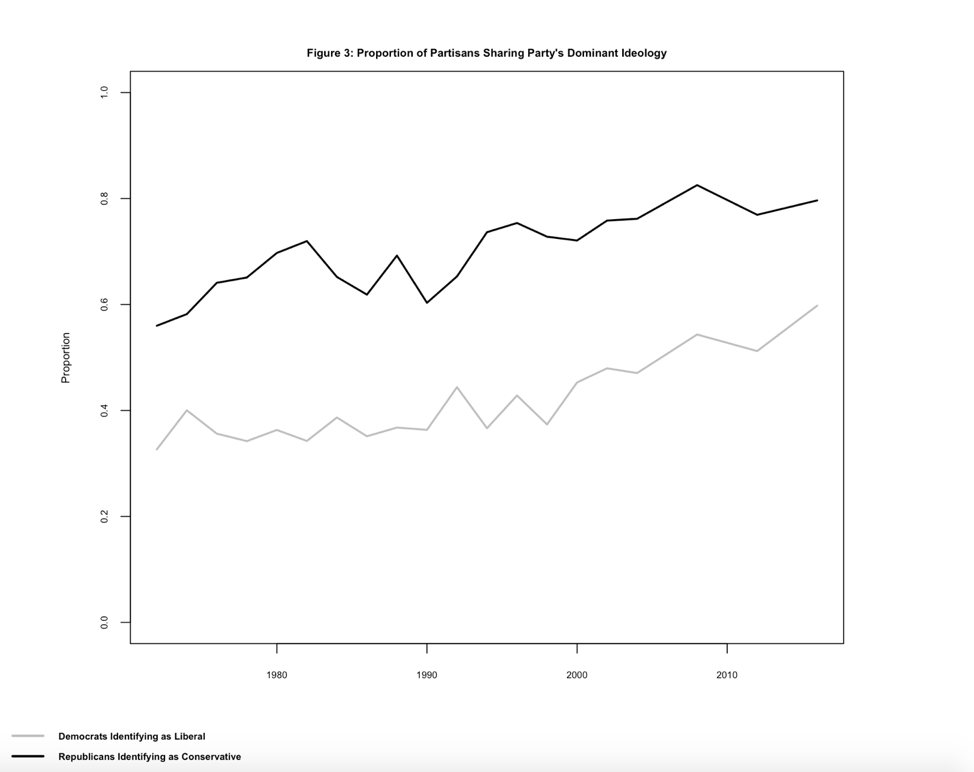

The progress of this homogenization of perceptions merits continued close attention. In the decade-plus since the 2008 financial crisis, partisan sorting has continued—that is, Democrats have increasingly come to hold liberal views, while Republicans have progressed in their adoption of conservative orthodoxy (see Figure 3). As this trend continues, it may fortify partisan perceptual biases against the reality of today’s economic turmoil. In the context of economic perceptions, it may mean that some sizable proportion of Republicans maintain their belief that the economy is improving despite clear evidence to the contrary. Such a development would teach political observers a great deal about how partisanship has strengthened in recent years.

It is worth noting, though, that even if perceptions of the economy do converge, it might not harm President Trump’s standing among those voters who are already predisposed to support him. Studying Great Britain during the economic decline from 2004-2010, Martin Bisgaard found that while partisans might agree on the dismal state of the economy, they persist in holding skewed beliefs about responsibility for the crisis (i.e., the incumbent party’s supporters felt that the government could not have avoided the crisis, while opposing partisans placed the blame squarely at the government’s feet). In his words, “Bias Will Find a Way.”

As such, while Republicans might eventually come to agree with their Democratic counterparts about the state of the economy, it is possible that—given the cause of the downturn—that they will not find fault in Trump’s response. The outcome of the 2020 presidential election will in large part hang on how these questions are answered.

David Brady is a professor of political science at Stanford University and the Davies Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution.

John A. Ferejohn is the Samuel Tilden Professor of Law at New York University Law School

Brett Parker is a JD/PhD student at Stanford University.