- International Affairs

- US

- Contemporary

- World

- US Foreign Policy

- History

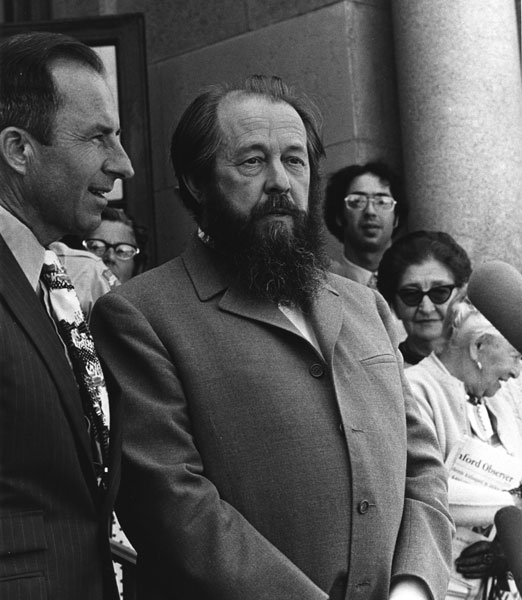

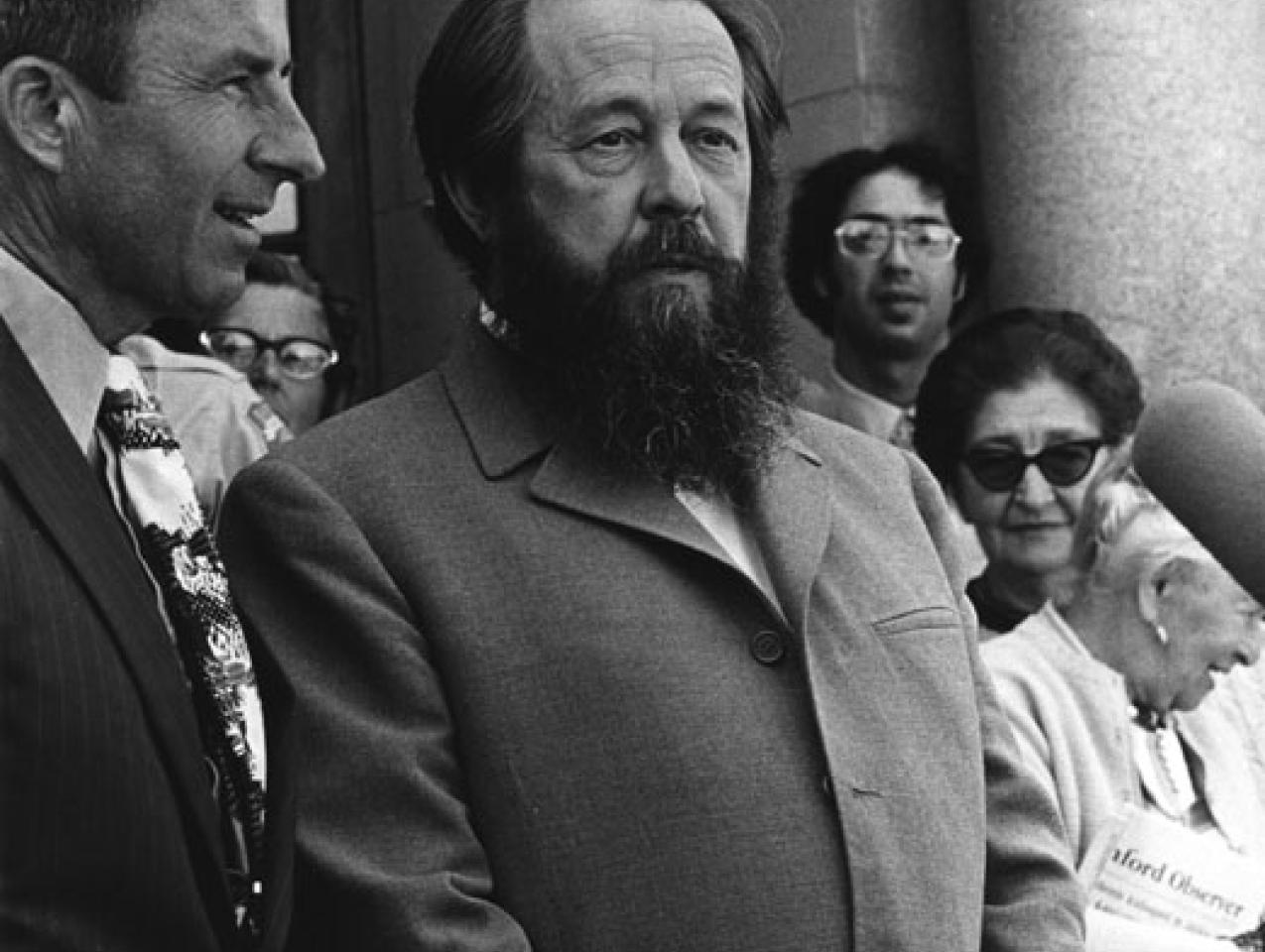

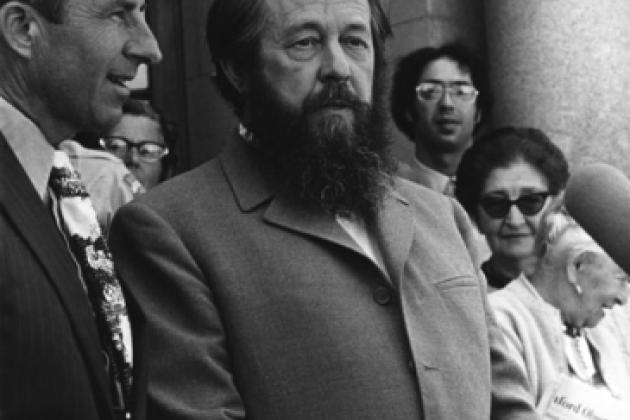

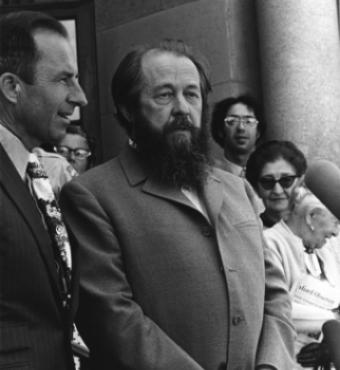

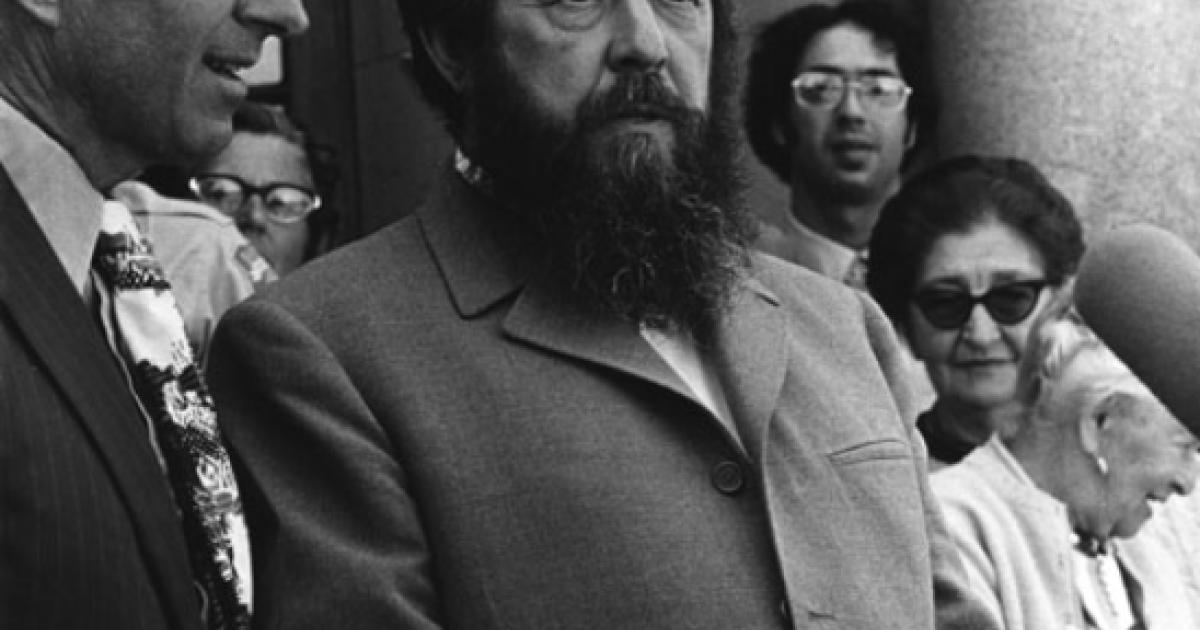

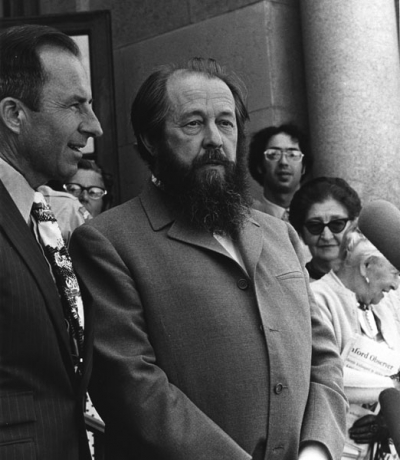

Those of us who had long been concerned to expose and resist Stalinism, in the West as in the USSR, learned much from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who died last August. I met him in Zurich in 1974, soon after he was expelled from the Soviet Union—the result of his masterpiece The Gulag Archipelago being published in Paris. He was personally pleasant; I have a photograph of the two of us, he holding a Russian edition of my book The Great Terror with evident approbation. He asked if I would translate a "little" poem of his. Of course I agreed.

The little poem, Prussian Nights, turned out to be 2,000 lines. Thankfully, he and his circle helped. It was an arresting composition, increasing our knowledge of him and his times—something worth reading, and rereading for its stunning historical background.

Solzhenitsyn was one of the most striking public figures of our time. How should one judge him? As a writer, up there with Pasternak? As a moralist, up there with Czeslaw Milosz? But he should also be judged as one who might have won two Nobel Prizes—not just for literature, which he was awarded in 1970, but also for peace.

In his public capacity, he felt bound to stand forward as the conscience of his people. He said, in a July 2007 interview in Der Spiegel, "My views developed in the course of time. But I have always believed in what I did and never acted against it." Yet above all, he saw himself as a writer—a Russian writer.

For most of us, Russian literature is like a triangle around Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov (Tolstoy is in his own class). Solzhenitsyn, on the strength of August 1914 alone, competes in the Tolstoy lane.

He first came to attention in the Soviet Union, and around the world, in 1963, with the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It is a short work, avoiding anything like sensationalism. Which is why, by great luck, it won permission to be printed—as was not the case with his later works. But as Galina Vishnevskaya (wife of Mstislav Rostropovich, in whose dacha Solzhenitsyn lived from 1968 while writing much of The Gulag Archipelago) put it in her autobiography: "The Soviet government had let the genie out of the bottle, and however hard they tried later, they couldn’t put it back in."

Some giants of Russian literature appear more preachy than is common in the West, a trait that brings us to what many see as weaknesses in the Russian tradition. Yet along with weakness there is also painful honesty.

Denisovich was followed by the well-known dramas that attended his whole career as a writer—especially surrounding his masterpieces, The Gulag Archipelago and The First Circle. Most readers will agree that Solzhenitsyn’s status as a world-class writer and sage depended on these works.

In his last years, he showed himself, as always, to be a Russian patriot. But this led him to take political stances that have been seen as anti-American. Indeed, even when he lived in this country and spoke publicly, as at Harvard in the mid-’70s, he was hard on much of America’s culture, although he focused on U.S. intellectuals’ delusions about communism.

Prussian Nights was about his role as an artillery captain in the Soviet army’s 1945 advance into East Prussia, a few weeks before his arrest for having referred disrespectfully to Stalin in a letter to a friend. It is also the first piece of writing in which one finds an American context. "Forward, forward, the front surges," he wrote, through the darkening winter,

Studebakers, to support us,

Are hauling lighter three-inch cannons:

"Hey, there, stovepipe! Grab our tail!"

Dodges—the three-quarter-ton ones—

Rush the forty-fives to fight . . .

Shorty mortars ride in place

At the back of Chevrolets.

I saw these transportation vehicles myself in the Balkans, at the other end of the long front. Not much sign of anti-Americanism there!

But things change. In these last few years of his life, Solzhenitsyn not only further stressed his Russian nationalism but made various attacks on U.S. policy and behavior—such as the NATO bombing of Belgrade (but not the Russian bombing of Grozny).

Some giants of Russian literature appear more preachy than is common in the West, a trait that brings us to what many see as weaknesses in the Russian tradition. First is the Russian feeling, without basis, that one is somehow being cheated—as in Gogol; second is a tendency to exaggerate or invent. Yet along with these weaknesses there is also painful honesty.

I did not sense the weaknesses when I met him. He was religious and Russian, but without exhibition—though it became clear he embodied Fyodor Tyuchev’s famous dictum that "Russia can neither be grasped by the mind, nor measured by any common yardstick—no attitude to her other than one of blind faith is admissible."

"The Soviet government had let the genie out of the bottle," said Galina Vishnevskaya, "and however hard they tried later, they couldn’t put it back in."

He remained staunchly anticommunist, noting in the July 2007 interview in Der Spiegel that the October revolution "broke Russia’s back. The Red Terror unleashed by its leaders, their willingness to drown Russia in blood, is the first and foremost proof of it." He also hoped that "the bitter Russian experience, which I have been studying and describing all my life, will be for us a lesson that keeps us from new disastrous breakdowns."

Such was his consistent view of Stalinism. He now combined it with approval of, and honors from, the new Russia that many feel is an obstacle to international peace and amity. Ideas have unintended consequences, even those of geniuses.