- History

Our navy’s senior admiral, John Richardson, made news last week by banning use of the Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2AD) acronym. The term had come into usage to describe the risks run by U.S. forces as adversaries—China, in particular—developed better long-range precision strike weapons. Richardson said the term “can mean all things to all people or anything to anyone—we have to be better than that…Instead, we will talk in specifics about our strategies and capabilities relative to those of our potential adversaries, within the specific context of geography, concepts, and technologies.”

It is of a piece with Hoover’s own Jim Mattis relegating to the dust bin of American military history “effects-based operations,” a concept popular to the point of breathless hand-waving while he was in command of U.S. Joint Forces Command. Declaring the concept “misapplied and overextended to the point that it actually hinders rather than helps joint operation,” Mattis encouraged planners to “return to time-honored principles and terminology that our forces have tested in the crucible of battle and that are well grounded in the theory and nature of war,” emphasizing “we must stress the importance of mission type orders that contain clear commander’s intent and unambiguous tasks and purposes and, most importantly, that link ways and means with achievable ends.”

Two strong tendencies exhibit themselves in ideas like A2AD and effects-based operations: being in thrall that technology can transform warfare, and that we will always have the best technology. Both are wrong. While trampling on new ideas may seem destructive of maintaining war-winning militaries, the true challenge for successful organizations—including militaries—is to know what not to change, and where to innovate. Militaries that successfully innovate carefully define the problem they need to solve, for example, the Germans restoring maneuver after World War I, and the U.S. Navy relentlessly experimenting in the inter-war years to identify our vulnerabilities in fighting across a vast Pacific.

A decade of fighting insurgencies, budget cuts, military services hesitant to undertake culture-challenging change, over-reliance on technology, and initiative-sapping reiteration that we have the finest military in the history of the world have lessened our margin of dominance in high-end warfare. Adversaries are gaining technologically and operationally, which will require the United States becoming much more serious about the undertaking of warfare than we have been in these last lazy years when we have had the luxury to lose our wars.

In evaluating the reasons the French military failed when confronted with the German invasion of 1940, A.J. Liebling concluded “the French had made the art of war so fascinating that the study must have stolen any reasonable general from the practice.” Both Richardson and Mattis were swatting away concepts splashily arrived at because new technology was thought to demand revolutionary new ideas. Military theorists since at least Guilio Douhet at the dawn of the airpower age have been trying to utilize technological innovation to upend the calculus of warfare. Technology certainly does affect how military operations are conducted, but it is no substitute for the baseline capabilities that have traditionally won wars, especially sound doctrine and commanders smart enough to know when to deviate from it. Time spent on breakthrough concepts like A2AD or effects-based operations would be better employed ensuring military doctrine is sound and fully understood throughout the force.

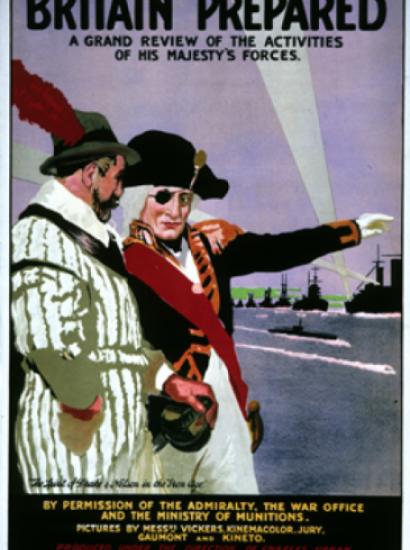

Admiral Nelson, the hero of Britain’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar on October 21, 1805, would cheer Richardson and Mattis. Nelson famously resisted incorporating the innovation of flag signaling orders among ships, relying instead on cultivating the good judgment of his commanders so they could anticipate each other’s choices and take initiative when opportunities presented themselves.

Andrew Gordon recounts in his terrific history of the Royal Navy that Nelson’s famous message at the commencement of the Battle of Trafalgar, “England expects that every man will do his duty,” was actually a joke. He was so well known to believe that signaling orders leeched initiative from commanders that when the first flag went up, Admiral Collingwood complained “I would to God Nelson would stop signaling. We know well enough what to do.” That is what a successful military sounds like.