- History

- US

- Revitalizing History

Back in August of this year I published in this outlet a series of essays centered around the topics of the American Revolution and the spirit of Philadelphia; the latter a coalescing energy that was the unexpected gift created when the Founders worked together to forge compromise at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. That spirit bonded us together in common purpose and created a nation, helping us get off to a strong start at the outset of the Industrial Age.

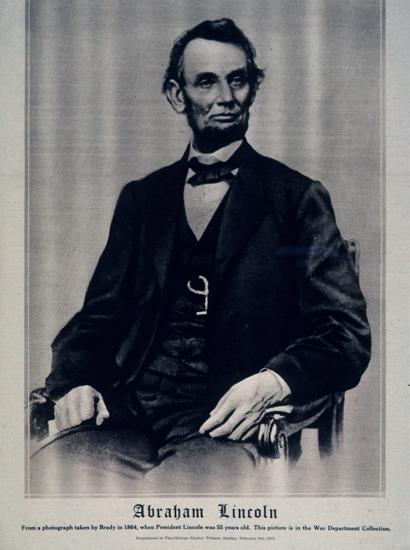

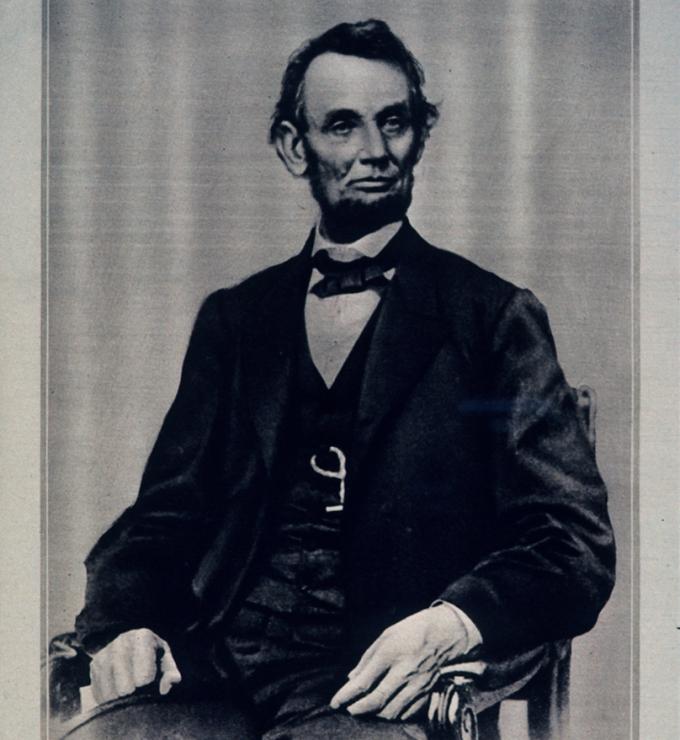

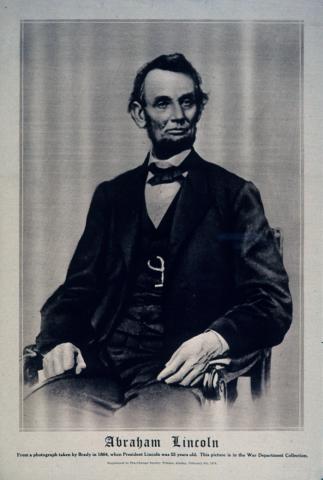

Over the next four essays I extend this argument, analyzing the leadership of President Abraham Lincoln during those crucial years just before and during the American Civil War. Ultimately, Lincoln’s murder in April 1865 robbed us of the leader we so desperately needed to help us unite after that bitter civil war and to recover the common political philosophy of the Founding, American Common-Sense Realism, and reawaken the spirit of Philadelphia, which gave us shared purpose and fostered national teamwork.

Lincoln and American Common-Sense Realism (CSR) in the Nineteenth Century

Although there were other important elements to it, central to American CSR was our newly ratified Constitution, which was itself a compromise meant to drive future compromises. In adopting the Constitution our nascent republic was attempting to accomplish something that none had ever done before—to survive and flourish where all others had eventually failed and fell. As they departed Philadelphia, it was hoped that this new Constitution and the common political philosophy that supported it would allow us to peacefully resolve differences and sustain our cherished way of life across time.

Before too long, however, it became clear that one of the key assumptions undergirding the Constitution was proving untrue—that it would eventually cause slavery to die out. Faced with that reality and a country that was increasingly coming apart, the system of government created in Philadelphia went into high gear doing what it was designed to do when under acute political stress—it produced compromise after compromise. First, Congress enacted the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Later they enacted the Compromise of 1850. Thereafter, they passed the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854. However, all these efforts at compromise proved futile, fueling more polarization and conflict, including “bleeding Kansas,” the caning of Charles Sumner on the floor of the U.S. Senate, and the rebellion led by John Brown in 1859. Then, during the presidential campaign of 1860, the southern states threatened secession if the anti-slavery candidate won. Our system of government, which seemed so deft at mediating even especially difficult political disputes, was struggling mightily when it came to the first-order moral question of slavery. Enter our sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln.

After George Washington, arguably no American president personified the spirit of Philadelphia more than Lincoln. A nearly entirely self-taught and self-made man, in many ways Lincoln was the living embodiment of the American Dream. He was raised in the backwoods of Kentucky and Indiana and was country poor. He had neither distinguished family name, nor ties to those in power. Yet, through pure hard work, determination, raw intellect, and superior emotional intelligence which he cultivated over time, Lincoln doggedly climbed the ladder of higher responsibility in American life.

Key to this, Lincoln was a voracious reader and through that activity came to align himself with the philosophy of the American Founding which balanced Lockean liberalism and the celebration of the citizen with New England-style communitarianism that emphasized the obligations we had to others and promotion of the greater good of society. Lincoln fully embraced this Founding approach and developed a devotion to German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s deontological ethical approach, and more broadly, “duty ethics.” In fact, as he was rising in national prominence, Lincoln would often speak in Kantian tones and concepts, including his somewhat pedantic but famous line, “as I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.” This, of course, is an example of the Kantian philosophical concept of the “categorial imperative,” which exhorts us to live as if the essence of our personal actions would instantiate a universal moral law.

As such, Lincoln appeared to be the right national leader for the 1860s because his views on slavery, in addition to being Kantian, appeared to be aligned with the Founders’ intent on this issue as expressed in both the Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed that all humans were created equal before God, and the Constitution, which while a compromise on this issue, intended to eventually end slavery through the enforcement of both the stipulation prohibiting international slave importation after 1808 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which prohibited expansion of slavery into the territories. Lincoln, in a series of speeches in the late 1850s, embraced the Founders’ intent aligning with James Madison’s argument in Federalist No. 42 that the Constitution would eventually cause slavery to die out. Also consistent with the Founding, Lincoln sought to accomplish this goal peacefully and in a manner that kept the Union whole.

Although elected as an outspoken critic of slavery and known throughout the country for his summoning “House Divided” speech, above all else, Lincoln viewed himself as the protector of our Union and the spirit of Philadelphia. That is why, after his stunning electoral victory in 1860, to the consternation of some of his strongest supporters, Lincoln went to great lengths to assure the southern states that his actions would not be precipitous and that they should stay in the Union and work with him to find a peaceful accommodation in accordance with the Founders’ intent. He was summoning all his talents and energies towards bridging this regional divide to unify us behind Founding principles. In this context we can better understand why in the opening months of his administration, despite facing the vexing reality that state after state was seceding from the Union to join the newly established Confederacy, Lincoln instructed his generals not to fire on their fellow citizens. He wanted to pursue all possible avenues towards a peaceful resolution to end the crisis with the Union restored and slavery on the path towards eventual extinction. If civil war ensued, the South would have to fire the first shot.

Of course, that’s exactly what happened on April 12, 1861, when Confederate batteries in Charleston fired on Fort Sumter. With the Confederate states now in open rebellion, Lincoln displayed keen agility, quickly pivoting from negotiation and diplomacy to military strategies that would end the war with reunification on his terms as soon as possible. Accordingly, he encouraged his generals to pursue Napoleonic-style decisive battle to force a quick surrender and selected senior leaders whom he thought best understood the art of that kind of warfare. However, when it eventually became painfully clear that on that score Confederate generals were just plainly better, Lincoln showed once again the ability to learn and adapt. Accordingly, he changed course and chose generals who had the stomach to see through a war of attrition that, given the asymmetry of resources between the North and South in favor of the former, was expected to bring about eventual victory. This was a big change in Lincoln’s senior leader selection criteria—he no longer prioritized the cleverest and most renowned commanders of maneuver, but rather those Army leaders imbued with a deep sense of realism and prepared to do what was necessary to finally end the war. Enter Generals Sherman and Grant.

Still, although Lincoln recognized the brutal reality of his current situation, he never lost sight of his larger strategic goal of restoring the Union, ending slavery, and moving forward together. This influenced the guidance he gave to his generals. In the spring of 1865, when it was clear that victory over the rebellious states was soon at hand, he instructed General Grant as he prepared to meet the vanquished Confederate General Lee at Appomattox, to “let ‘em up easy.” Grant then dictated charitable terms of surrender where Confederate officers were able to keep their horses and sidearms and return home to southern farms in time for spring planting.

These gracious and merciful instructions from Lincoln were neither coincidental, nor off-brand. They were entirely consistent with his full embrace of Founding principles and the spirit of Philadelphia. A clear pattern of this behavior can be discerned from a close examination of the historical record. For example, this approach was also on display the previous month as President Lincoln stood up before an esteemed gathering at the U.S. Capitol for his Second Inaugural Address and stated, “with malice towards none and charity for all, we will bind up the wounds of our nation.” It was also evident still earlier that year when Lincoln expended enormous political capital to secure the passage in Congress of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution permanently ending slavery. This approach also was apparent the previous year when he decided to stand for re-election in 1864 not as a Republican, but as the head of a Unity ticket, choosing a member of the Democratic political party, Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson, as his vice-presidential running mate. In fact, although far from perfect (here referring particularly to his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus for Northern war dissenters), a careful review of his entire performance as president reveals that Lincoln stayed true to his convictions and Founding principles despite the enormous pressures of the Civil War.

Lincoln also had a powerful vision for a post-war America where all political factions worked together, from “Radical Republicans,” some of whom wanted to execute or exile former Confederate officers, to “Bourbon” southern Democrats bent on reestablishing the status quo ante. Similar to the Founding experience, in Lincoln’s vision for our rebirth after the war, the spirit created as these disparate forces worked together would moderate their respective extreme views, thus ensuring that all Americans (including former Slaves) were henceforth treated equally under the law. Alas, tragically an assassin’s bullet denied us all of that.

Lincoln’s Assassination and the Decline of American CSR

In high school we all learn the basic history of the American Civil War and its aftermath, including the failure of Reconstruction, the rise of the KKK insurgency, and President Grant’s efforts to defeat and dismantle it. Less taught, however, was the dirty deal that finally resolved the disputed presidential election of 1876 when an ad hoc commission established by Congress voted along party lines to award the office to Rutherford B. Hayes despite the fact that he won neither the popular vote nor the initial Electoral College vote. Only several months later, Hayes—despite his public pledges to the contrary during the campaign—abruptly pulled Union troops out of the South effectively ending Reconstruction. Jim Crow laws soon followed as the “Bourbons” effectively reasserted power in the South, hammering the final nail in the coffin of Lincoln’s unified vision for our nation’s future.

Among all the casualties of that vicious war, we must add not only Lincoln himself, but also our Founding philosophy, which went into decline as we buried our sixteenth president. Indeed, Lincoln was firmly committed to uniting us behind American CSR, but in the years that followed his murder we philosophically drifted apart, becoming vulnerable to newer ideas coming by way of Europe, especially German Idealism and Logical Positivism. You can read my latest book to get a full accounting of this argument; but summing it up here, after the Civil War we largely abandoned Founding principles and have oscillated ever since between progressive, libertarian, and populist ideas—all alternatives lacking the balance we had with the blending of Lockean liberalism and New England-style communitarianism under American CSR, an approach many have characterized as American exceptionalism. All ideas have consequences (good and bad) and changing them makes a difference. Are we better off for replacing Founding ideas and how different might our future have been under Lincoln’s leadership after the war?

The next essay covers the darkest days of the war for the Union, which militarily included the period after Fort Sumter up until the Battle of Gettysburg and the capture of Vicksburg in July of 1863, but politically continued well into the summer of the following year when calls to oust Lincoln and to sue for peace with the South resonated with many, including some of the leaders of the Republican party. In the face of these monumental challenges some Union leaders were ready to give up the cause but Lincoln, in some ways similar to General Washington’s leadership during the American Revolution, somehow found the strength to keep going—to fight on to victory.

We must learn from these consequential moments in our history if we have any hope of recovering Founding principles and reawakening the spirit of Philadelphia.

Chris Gibson is a decorated Army combat veteran, a former Member of Congress, and a Participant of Hoover’s Working Group on the Role of Military History in Contemporary Conflict. This essay was drawn from Gibson’s latest book, The Spirit of Philadelphia: A Call to Recover the Founding Principles, published by Routledge in 2025.