- History

- Military

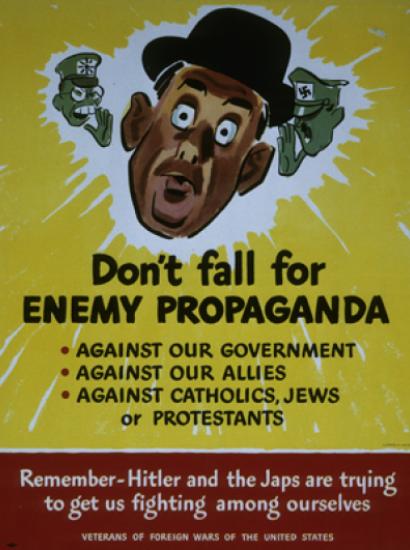

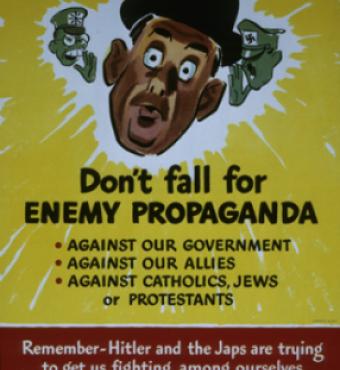

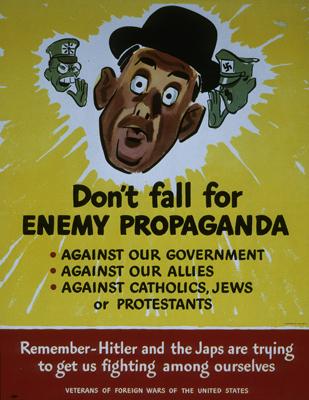

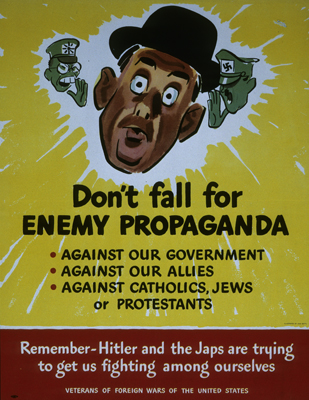

During World War II English-speaking female broadcasters taunted Allied soldiers, who nicknamed the anonymous radio personalities “Tokyo Rose” and “Axis Sally.” GIs would often listen to the broadcasts for the entertaining music, mostly ignoring the outlandish claims and overt propaganda directed their way. Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels specialized in selling the “big lie” to the German people, combining grand spectacles, radio, motion pictures, and print journalism to hammer home his “talking points.” When Allied armies overran Germany and Japan, however, the propaganda stopped; Goebbels committed suicide in lieu of surrender and appearance before a war crimes tribunal. Axis Sally and Tokyo Rose returned home to the United States to face trial and imprisonment.

New technologies have spawned new propaganda methods, primarily social media driven by the Internet. The power of these new tools has raised concerns about the ubiquitous presence of jihadist propaganda in the cybersphere. The American traitor Anwar al-Awlaki mesmerized untold numbers of his fellow Muslims with online videos uploaded from his perch in Yemen before being killed by a drone strike in September 2011, and his digital persona lives on today. The worry, then, is the seemingly immortal life of Islamist propaganda in cyberspace.

The dramatic rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham and its territorial conquests in 2014 empowered the group to reach out to co-religionists around the world with professional propaganda in a variety of outlets. These messages enticed Muslims to join the Islamic State and enjoy the fruits of conquest: women, plentiful food, life under Islamist governance, and participation in jihad against the mortal enemies of Islam. As long as ISIS appeared to be winning, its narrative appealed to tens of thousands of like-minded Muslims, who made their way to the caliphate through the porous Turkish-Syrian border.

Those heady days seem long ago. U.S.-backed military operations in Iraq and Syria have smashed the Islamic State; remaining ISIS forces are now limited to a small sliver of territory on the Syria-Iraq border. Air strikes and combat action have killed more than 45,000 ISIS fighters. Just as importantly, the ISIS propaganda network has crumbled, with production of media pieces down tenfold since mid-2015. Furthermore, the slick vision of utopia-on-the-Euphrates has been replaced by messages of sacrifice in battle, not exactly the stuff of appealing recruiting ads.

We are learning that life in cyberspace has its limitations. Although messages can live there, people cannot. During operations pursuant to the U.S. surge of forces to Iraq in 2007-2008, the propaganda networks of al-Qaeda in Iraq, the forerunner to ISIS, were shattered. The defeat was catastrophic enough to force reorganization and the group’s rebranding. It remains to be seen what parts of ISIS will emerge from the wreckage of its self-proclaimed caliphate. Although modern day Joseph Goebbels, Axis Sallies, and Tokyo Roses are more likely to die from a drone strike than face justice in a war crimes tribunal, the impact on their propaganda operations is the same. It’s tough to sell would-be recruits with images of death and destruction in Mosul and Raqqa. It’s even harder when the propagandists are dead and their messages discredited.