- Economics

- Budget & Spending

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- California

Editor’s Note: This essay is based on Rauh, Joshua and Ryan Shyu, “Behavioral Response to State Income Taxation of High Earners: Evidence from California,” NBER Working Paper #26349

States often increase tax rates with the assumption that those tax increases will yield higher revenues which the governments can then use to provide public goods. However, typically these assumptions are based upon the notion that the targeted taxpayers’ incomes and business activities within the state at the time of the tax increase will remain constant in subsequent years. More specifically, state officials often do not pay serious attention to the idea that these taxpayers may simply move out of the state or shift their business activities out of the state, which would cause a significant drop in potential taxable income.

One such example of a tax increase took place in 2012 when California governor Jerry Brown advocated and campaigned for the passage of Proposition 30, the “Schools and Local Public Safety Protection Act”. This effort was based on a desire to preserve statewide education funding and close a budget gap by instituting new tax increases on high-income Californians that increased the top marginal tax rate in the state from 9.3% to 13.3%

In total, the California Department of Finance believed that the new tax rates would result in an overall increase in combined tax revenue of $8.5 billion over the tax years 2011-2012 and 2012-2013. With this increase in tax revenue, there would be an additional $2.9 billion dollars constitutionally required for the minimum funding of schools and community colleges. The remaining $5.6 billion dollars in the General Fund would be appropriated for the purpose of closing the budget gap.

Ultimately, the wealthiest one percent of California taxpayers, individuals making incomes of more than $533,000, were expected to provide approximately 78.8 percent of the revenues raised by Proposition 30's tax increases, while California's top five percent of taxpayers, individuals making incomes of more than $206,000, would contribute 81.2 percent of the revenues raised. The tax rate would amount to a 1.1 percent increase in income taxes for the top one percent of California taxpayers and an increase in 0.05 percent for the top five percent of California taxpayers.

But what would happen to those projected figures if significant numbers of high-income taxpayers decided to move out of the state, thus removing their incomes from the pool of taxable income? And what would happen if high-earners who remain California residents produce less taxable income for the state than they otherwise would have, by engaging in greater tax avoidance for example? In economics, the term for these actions that taxpayers might take is “behavioral responses”.

Our work uses a unique micro-dataset consisting of the universe of household tax filings from the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB). We find that in the case of Proposition 30, there was both a significant loss of taxable income and significant increase in out-of-state migration on part of the affected taxpayers. Overall, among high-income California taxpayers, outward migration and behavioral responses by stayers together eroded 45.2% of the expected windfall tax revenues within the first year of the reform, and more thereafter.

Compared to other efforts in the literature on the behavioral response of taxation, our work has several advantages. First, the universal micro-data from a state tax authority during a time period of aggressive income tax increases provides new opportunities for analysis. Second, the availability of non-resident as well as resident tax returns allows us to examine the evolution of the federal taxable income of high-income taxpayers who do not live in California, but nonetheless must file there due to a small portion of their income having California sources. Our empirical design allows us to compare those incomes with to the federal taxable income of similar high-income taxpayers who live in California.

In this setting, we find evidence of much stronger behavioral responses of high-income taxpayers than has been found in prior research efforts in the public finance literature. We calculate that 45% of the state’s expected windfall gain from the tax increase was in fact eroded by behavioral responses within just the first year of the tax law, and over 60% in the second year.

Furthermore, the estimates in our paper predict further substantial California outmigration effects and intensive margin effects from the 2017 federal legislation that capped the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, which had become particularly valuable to California taxpayers. In fact, the elimination of the SALT deduction hit high-income California taxpayers with the force of 82% of another Prop 30.

Our results therefore predict that as of today, California is on the wrong side of the so-called Laffer Curve. That is, the only way that state authorities can reasonable increase revenues relative to what they would be without further policy action is to cut tax rates.

Summary of Law and Data

After the formal passage of Proposition 30, California's upper-income taxpayers saw three newly established personal income tax rates. More specifically, the new tax brackets were the following:

- 11.3 percent tax bracket for single filers' taxable income between $300,001 and $500,000 and joint filers' taxable income between $600,001 and $1 million; and

- 12.3 percent tax bracket for single filers' taxable income above $500,000 and joint filers’ taxable income above $1 million.

These tax rates would initially be in effect for seven years (from tax year 2012 through tax year 2018). In 2016, voters extended the higher rates through 2030 when they passed Proposition 55.

To estimate the behavioral response of California taxpayers, we rely on administrative data from the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB). This data source contains the universe of California tax returns from 2000-2015. A key feature of these data is that residents, non-residents, and partial-year residents were all coded identically, making tracking these individuals over time much easier.

Moving Out

We begin by considering the wealthiest taxpayers in California, those earning over $2 million per year. The rate of departure of these individuals from California spiked by 42% relative to before the passage of Proposition 30. For those whose taxable income would have put them in the new top bracket for three years running the spike was even larger, at 48%, with the result that in the year of Proposition 30, over 1.7% of these high-income taxpayers left the state.

Prior work by other researchers had argued that Proposition 30 had a small impact on moving out, as it had counted only situations where a high-income taxpayer first files as a resident, then a non-resident or partial year resident, and then stops filing entirely. However, given the ties that high-income California taxpayers have with California, and the state’s requirement that any individual with any California-source income must file a tax return, many households that change their state of residence still file a California tax return as a non-resident. We found that situations where high-income taxpayers initially file as a resident of California, and then for multiple subsequent years file as a non-resident lead to the loss of approximately 84 of their taxable income for the state. These situations should clearly also be counted as outward migration.

The dramatic increase in outward migration was smaller than it otherwise would have been in the absence of federal legislation that occurred at the same time. Simultaneous to the passage of Proposition 30 was the passing of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (“ATRA”) on the federal level. Due to some of the changes, this reform lessened the tax benefit of leaving California. If ATRA had not been passed, the treatment on California households’ relative average tax rates would have been 23-40 percent higher. Assuming taxpayers understood the actual net change in incentives due to the interplay between both the state and federal tax changes, this analysis suggests that the rates of departure among higher income earners would have been even larger in the absence of federal legislation.

Those Who Stay Produce Less Income

To determine the causal impact of the California tax reform, we defined the “treatment group” of taxpayers as those taxpayers who from 2009 to 2011 filed as California residents, and further who for each year earned taxable income which would have placed them in the range of the top-bracket as newly introduced by California Proposition 30 had those tax brackets been in effect in the prior years. We also required that each “treated” taxpayer file as a California resident through 2014, to ensure that we focus only on the “stayers”. We chose this strategy to attempt to avoid singularity events (i.e. startup IPOs or other liquidity events) where taxpayers’ incomes may potentially revert to other income brackets.

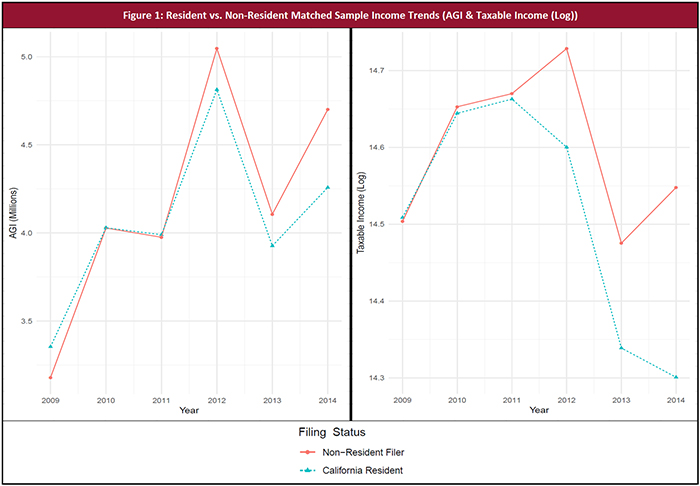

We followed the levels of Adjusted Gross Income (“AGI”) and Taxable Income to estimate the intensive margin responses for these groups. When merely viewing AGI and Taxable income trends for both groups, there appears to be parallel trends for between the groups for the tax years 2009-2011 (SEE FIGURE 1).

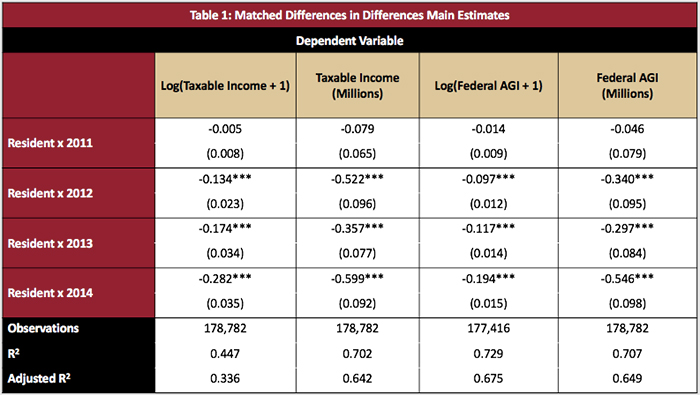

We found there to be no statistically or economically significant effects to AGI or Taxable Income for 2011, which confirms the aforementioned graphical analysis. However, we do estimate economically and statistically significant effects of Proposition 30 in years 2012-2014. The average high earning California resident reports $0.522 million less in 2012 income (the year to which the tax increase was retroactive), $0.357 million less in 2013 income, and $0.599 million less in 2014 income (SEE TABLE 1).

While past literature has concluded that the elasticity of taxable income with respect to marginal tax rates for the average taxpayer is in the range of 0.1 to 0.4, our estimates imply an intensive margin elasticity of 2013 income for high-income individuals with respect to the marginal net-of-tax rate of 2.5 to 3.3. This estimate is clearly much higher than the average estimates reported in the literature.

Conclusion

The issue of behavioral responses to income taxation is an important question in academic and policy circles. Understanding these behavioral responses is and will continue to be crucial if states expect to institute effective fiscal tax policies. In this paper, we draw upon rich microdata on the universe of tax returns for the California FTB to show that high earners, on whom California’s economy is highly dependent, respond strongly to tax increases.

Combining the estimated lost revenues from movers with the estimated lost revenues from the reduction in taxable income of the stayers, we calculate that 45% of the state’s expected windfall gain from the Prop 30 tax increase was eroded by behavioral responses within the first year of the tax law, with even higher estimates thereafter.

Some might look at this as “good news” that the state of California was at least within a couple years of the tax reform not yet over the top of the Laffer Curve, the point at which raising tax rates results in the state collecting less income. The bad news, however, is that taxpayers may still continue to move and engage in tax avoidance in response to these higher taxes for years to come.

Furthermore, the capping of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction by federal tax legislation that went into effect in 2018 drove a further wedge between the cost of living in California and the cost of living in states with substantially lower income taxes. Our results imply that Californians will now respond almost double as much to the state’s high taxes as previously, which in turns puts California now on the wrong side of the Laffer Curve. Further analysis of tax data will be required to assess the total distortionary effects of these two major changes in tax policy.