- Security & Defense

- US Defense

“Of the four wars in my lifetime, none came about because the U.S. was too strong.” —Ronald Reagan

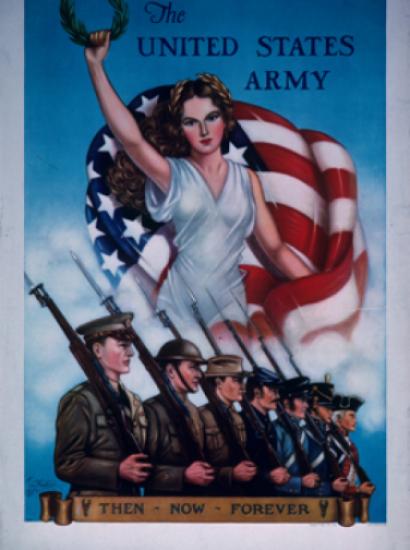

As was widely anticipated, the 2015 defense budget proposal follows the narrative of the postwar drawdown of the U.S. Army. As Secretary of Defense Hagel rightly states, “The world is growing more volatile, more unpredictable, and in some instances more threatening to the United States.” It therefore may seem ironic that a Viet Nam veteran infantryman serving as Secretary of Defense would foreswear future ground wars given our Nation’s history. As we look forward to the possible impacts of reducing our Nation’s Army to pre-World War II force levels, it may be prudent to recall the instruction of history. In each decade from the 1940s, 50s, 60s,

As was widely anticipated, the 2015 defense budget proposal follows the narrative of the postwar drawdown of the U.S. Army. As Secretary of Defense Hagel rightly states, “The world is growing more volatile, more unpredictable, and in some instances more threatening to the United States.” It therefore may seem ironic that a Viet Nam veteran infantryman serving as Secretary of Defense would foreswear future ground wars given our Nation’s history. As we look forward to the possible impacts of reducing our Nation’s Army to pre-World War II force levels, it may be prudent to recall the instruction of history. In each decade from the 1940s, 50s, 60s,

70s, 90s, 2000s, through 2014 the United States has engaged in sustained ground wars, regardless of the political party in power or administration preference for protracted land campaigns, counterinsurgencies, or nation-building exercises. Even during Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush’s brief post-Cold War peace-dividend decade of the 1980s, the United States scrimmaged in the Caribbean, fighting in both Grenada and Panama.

The world is indeed volatile and uncertain; Mideast turmoil continues, Iranian proliferation concerns are unresolved, North Korea remains a precarious but active belligerent in North East Asia, and Ukraine may soon see Russian tanks dictating political terms. To the last point, the only U.S. tanks in Europe stand ready not in the motor pools of brigade combat teams, but as training sets in pre-positioned storage sites. The U.S. Navy and Air Force, the finest in the world, cannot stabilize such political flashpoints from offshore or regional bases. Our Air Force and Navy dominate the commons of air, space, and sea, but they cannot by themselves preserve political decision space for fledgling governments or allied nations under pressure from internal or external opportunists. The Air Force and Navy provide assured access to potential combat zones, but their presence is transitory in nature, providing effects that shape the theater but do not conclude hostilities. The U.S. Army’s mission, drawn from Title 10 of the U.S. Code, is to win America’s wars by providing prompt and sustained landpower. The nation’s Army in the very near future may not be able to do that in more than one place at a time. Despite the tremendous competence of Special Operations Forces, the unblinking stare of UAVs and their precision strike options, the crowded littorals and mega city conflicts of the future (or old-think problems in North Korea, Iran, Syria, or Ukraine) will require combined arms formations on the ground to deter conflict or deliver a decision. However, as noted quite astutely by the Chief of the Australian Army in regards to China, America’s ability to shape the security environment and deter conflict is underpinned by our ability to fight and win wars.

Former Secretary of State George Shultz recalls that President Reagan used military force only a hand full of times. These brief operations in Grenada and Libya resulted in positive strategic effects balanced against the tensions of the Cold War. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the post-Cold War international order promised to be one of free markets, a trend toward the ascendance of democracy, limits on nuclear proliferation, and waning wars of aggression. That world is unraveling. The unraveling accelerates without American leadership and the assurance and deterrence provided by the moderating influence and credibility of American arms on the international stage. The pace of U.S. military operations has demonstrably increased over the past 20 years, even prior to 9/11. There has been no indication that the pace of requirements will lessen going forward, only our willingness—and soon capacity—to address those requirements will lessen with the military instrument of national power in the lead or in support of diplomacy and economic efforts.

Policymakers have stated that our nation can accept the risk of a smaller Army. This notion is supported by the assertion that the American people will no longer support extended land wars. The strategic surprises of December 7, 1941, June 20, 1950, and September 11, 2001 saw the will of the people and the government change overnight. Today’s All Volunteer Force was previously drawn down (from over 770,000 active duty Soldiers in 1989 to 480,000 on September 10, 2001) in the wake of a transformed world order following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Deep cuts to the ground forces were underway that year as Saddam Hussein’s Iraq miscalculated and seized Kuwait. Even deeper cuts were envisioned by President George W. Bush’s administration in light of technologically enabled Net Centric Warfare at the dawn of the 21st century. An All-Volunteer Force of 480,000 active duty soldiers proved insufficiently sized to meet the nation’s pressing security requirements of two medium sized counterinsurgency campaigns in the wake of 9/11. Rapid force reductions to the current All-Volunteer Force will cast long shadows over the future; not least of which will be the credibility of the institution that will show thousands of soldiers the door through involuntary separations even as combat continues in Afghanistan.

A future security environment predicated on an active duty Army with 440,000 Soldiers (or 420,000 should budget sequester persist post-2016) might yield unintended second and third order effects. Assurance of allies and deterrence of adversaries will suffer inasmuch as the flexibility of our military to respond with sustained force to more than one strategic surprise is constrained. The choice for Japan and South Korea not to seek a nuclear deterrent could conceivably be reconsidered. Likewise, the Gulf Sunni states may not rely entirely on the prompt and sustained presence of the U.S. for deterrence in response to an Iranian nuclear state. It is not inconceivable that a rogue nation or group of state or non-state actors could act in concert or independently at or near the same time to challenge U.S. interests abroad or those of our allies. A less robust military instrument of national power may prove deleterious to our diplomatic efforts to forestall these bad actors on the international stage.

An Army of 440,000 may not appear provocatively weak in the eyes of adversaries today, but in a time of uncertainty and growing threats, we must very carefully consider the invitation to miscalculation this decision may open for the future. If our nation chooses to step back from a leadership role in the world, we must be willing to accept that eventually others will fill that role.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.