- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Budget & Spending

- Energy & Environment

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

The high price of oil was front-page news again this year. Reporters demanded to know first why the prices had risen so high, and second what, if anything, should be done about it. The short answer to the first question is that the increase was due to contractions in the supply of oil, driven by instability in the Middle East. The short answer to the second is that we should do nothing at all.

The greatest casualty of the debate over oil prices is the way sensible market responses to scarcity are turned into grist for the political mill in an election year. The blame game between the political parties is likely to lead to flawed reform proposals that offer no short-term relief but do impair the long-term efficiency of oil markets.

Without question, the problem can be traced back to a renegade Iran. For good and sufficient political reasons, the West has come to see the Iranian nuclear threat as more than bluster. Indeed, it poses far greater risks to world peace and the political order than even a major disruption in oil supplies.

Hence an anxious West has now put into place a reasonably effective concerted effort to cut off Iran from the world’s banking system, and to block the use of Iranian oil internationally, which has been made easier by the Saudis’ willingness to expand shipments into the world markets. The Iranians have not been idle. They have cut off exports to the United Kingdom and France, a largely symbolic move. Their threat to close the Strait of Hormuz, the path for about one-third of the world’s oil supplies, is not symbolic. Nor is the movement of the U.S. aircraft carrier, the USS Abraham Lincoln, into the Strait of Hormuz.

Such developments drove up the baseline price of Brent crude from the North Sea, which undoubtedly will eat into the pocketbooks of many Americans. The blogosphere is thus filled with accounts of how ordinary Americans are being forced to tighten their belts as a result of the high price of oil. W. Howard Coudle, an ordinary American recently quoted by the Associated Press, said the rise of his monthly gasoline bill from $60 to $80 had made a difference: “We’re going to have to drive less, consolidate all our errands into one trip. It’s just oppressive.”

His are genuine hardships, as are those of millions of other Americans. Coudle’s heartfelt claim of oppression is an early harbinger of political discontent, but his private adaptive responses make far more sense than any political response to the rising price of oil. The question at hand is how best to respond to the disruptions in oil supplies, not to pretend that these disruptions do not exist. On this score, the great advantage of a market system is that it forces Coudle (and everyone else) to think hard about the relative value of the goods and services he consumes and to cut back in a thrifty, rational fashion. In good times and bad, people always have to decide which goods and services to spend their incomes on, and which to forgo.

Price movements give them an accurate, instantaneous, and impersonal picture of how other people value var-ious goods and services. When oil goes up, its least valuable uses are the first to drop out of the system. The decisions are typically made on a continuous basis, so that if some people find they have cut back purchases by too much (or too little), they can increase (or decrease) their purchases in the next pricing period. Spurred on by these price increases, people can also change spending patterns elsewhere to offset the inconvenience of the higher prices for oil products. Purchasing a hybrid car, insulating your home, and moving closer to work are just some of the many ways to save money. Good luck to Coudle, who provides an object lesson in how that task should be done.

WISDOM THAT ISN’T

The great risk is that the government will undermine the market by resorting to centralized devices to cap the price increases or dictate its collective vision of the just price. Now is the time to recall the lessons of Friedrich Hayek’s best writing, the scholarly essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society” (1945), which is about the superiority of a decentralized price mechanism in response to systemwide shocks. As he reminds us, “The knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all separate individuals possess.”

W. Howard Coudle is one such bit: he knows far more about his peculiar situation than any analyst or regulator. Imposing any system of government subsidies or controls will disrupt the market’s vital process of continuous adaptation; it will also cost a fortune to put into place. The “hands off” motto of laissez-faire capitalism has never been more pertinent than in this oil-price problem.

This reasoning has been lost on our leading political figures on both sides of the aisle. The point is not that every proposal is wrong. Rather, it is that the reforms have nothing to do with the short-term shifts in oil supplies. Once that extraneous element is removed from the discussion, it looks as though neither side in the current political environment has anything sensible to say about the increasing prices.

Start with the Republicans, who salivate at the prospect of using the rising price of oil against President Obama. But just what does House Speaker John Boehner hope to accomplish when he tells his fellow Republicans to seize on the gas-pump anger, bemoaning the $4-plus prices at the pump? He can’t responsibly say that he wants these prices to be lower if they rose in response to scarcity. Nor can he lay the blame for the current dislocation at Obama’s feet, whatever else the president may have to answer for.

The only way to lower oil prices is to subsidize its consumption in some form, which is where Boehner’s thinking necessarily leads. Those subsidies have to come from somewhere, which means new or higher taxes. Another problem with subsidies is that they lead to the relative overproduction of the subsidized product and the relative underproduction of its close rivals. The president himself has called for greater subsidies for solar energy, whose entrepreneurs should be left to sink or swim on their own. Boehner is making the same mistake for oil. He needs to avoid panicking in response to bad news.

Senator Rick Santorum also needed to tone down his rhetoric: “They want higher energy prices. They want to push their radical agenda on the public. We need a president who is on the side of affordable energy.” Not so. In this environment, higher prices are the best response to contracting supplies. There is, therefore, nothing radical in President Obama’s decision to stay on the sidelines on this matter. But there was a great deal of freighted meaning when Santorum mentioned “affordable energy,” for it called to mind a policy of state subsidies that distort relative prices across the board.

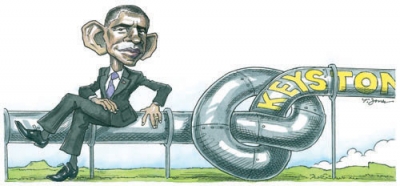

Newt Gingrich offered a solution that was no better. He expressed the desire to keep gasoline prices at $2.50 per gallon, by national petition no less. He was right, I think, to urge increased domestic drilling and call for the opening of the Keystone XL pipeline. The president may have made the worst of all possible decisions in killing a pipeline that could have cemented America’s relationship with Canada, rationalized production and distribution of oil in the United States, and reduced the risk of pollution by blunting spillage risk from tankers steaming toward China loaded with oil. But no evidence whatsoever suggests that opening the pipeline or increasing domestic oil production, both desirable, would lead to some mythical $2.50-per-gallon price at the pump any time soon.

Once the right institutional arrangements clear the way on drilling and the pipeline, supply should increase, and, on average, prices should decline as consumption increases. But we must never tie government policy to particular price levels. Politicians must set the right institutional arrangements and then let the cost of production and relative demand set prices.

“FAIR SHARE”—A CRUDE CUDGEL

The political ignorance on the Republican side was, alas, fully reciprocated by unwise pronouncements from the Democratic side. The president’s personal statements exuded sympathy for those whose lives are made more difficult by higher gas prices, but words alone don’t translate into constructive policy. Nor did it help that Alan B. Krueger, who chairs the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, took the occasion to note that the reduction in the payroll tax helps to soften the blow from these prices.

The payroll tax reduction is one way to pour money into the economy, and it is surely better than some top-down stimulus program that spends the money on pork. But the difficulty with the payroll tax reduction remains: the long-term return to economic health is not facilitated by short-term fixes that add uncertainty to the system without addressing the serious structural defects of the current tax code, which contains too much progressivity and too much complexity.

Comments from Democratic firebrands only made matters worse. “House Republicans are very good at using every argument they can to shield oil companies from paying their fair share. They have been relentless and fearless protectors of oil company profits.” So said Congressman Steve Israel, who used the term “fair share” as shorthand for saying that every tax the oil companies pay should be increased. Mindless populism like this assumes that oil company profits are in and of themselves a bad thing, but everything else being equal, rising profits generate more jobs, more dividends, and, yes, more tax revenues than can be wrung out of a stagnant industry. The oil industry is so complicated that it is easy to postulate that it benefits from some unwise subsidy. But if subsidies are unwise, so too are any special regulatory burdens or taxes on oil companies. All should be removed to achieve the central goal of a tax system: to preserve the same investment priorities across sectors and firms that would exist in the hypothetical non-tax world.

The overall lesson is that the desire to meddle politically in economic matters only gets worse when politicians start from this erroneous, but shared, premise: simple changes in prices count as evidence of a market failure that justifies government intervention. They don’t. Price increases should not lead to a call for price limits. The real problem is the trouble brewing in Iran and the Strait of Hormuz. Politicians should neither panic nor pander, especially when their political energies are needed to reach a diplomatic or military solution for a serious international breakdown that requires our urgent and unified national attention.