- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- China

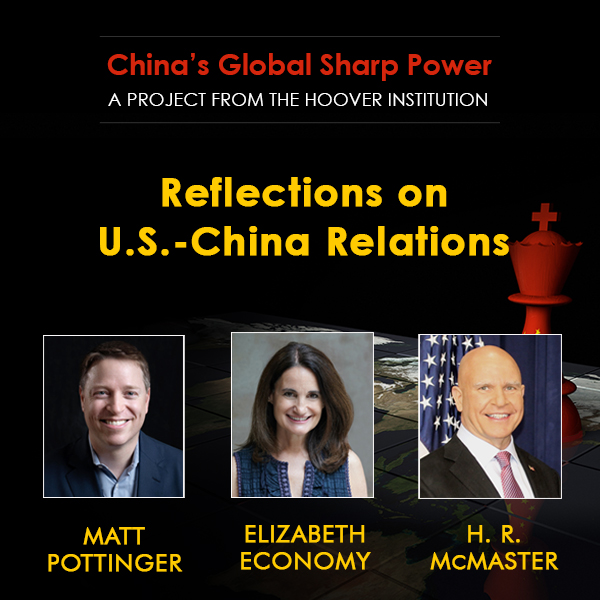

These remarks were delivered by Hoover Distinguished Visiting Fellow Matt Pottinger on March 10, 2021 at the Hoover Institution. To watch the full discussion, click here.

Thanks, H.R., Liz, Glenn, and Larry Diamond for hosting this event. And thanks to Dr. Condoleezza Rice for her leadership of such a strong team at the Hoover Institution. During my four years in the White House, Stanford University’s Hoover Institution distinguished itself as one of only a handful of think tanks that consistently published creative, bold, and truly independent research and recommendations related to China. I’m very proud to have recently joined the Hoover team.

Tomorrow marks 50 days since President Biden was sworn into office. I’d like to focus my prepared remarks today on 1) Beijing’s current approach to the United States; 2) my take on President Biden’s approach so far toward China; 3) and what it all means for the U.S. business community.

I’ll close with a couple of thoughts about the mindset I believe America should adopt—as a government and as a people—to ensure we win the competition against Beijing’s vision for a predominantly authoritarian world. It’s a competition that we very much can, and very much must, win. I’ll try to be succinct so we have plenty of time for a lively discussion.

BEIJING’S TERMS

So, what is Beijing’s approach? In the weeks that surrounded President Biden’s inauguration, Chinese leaders waged an information campaign aimed at the United States. The flurry of speeches, letters, and announcements was not, as news reporters first assumed, addressed mainly to the new administration. It was actually an influence operation targeting the U.S. business community.

The Communist Party’s top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, spoke to a virtual audience of American business leaders and former officials in early February. He painted a rosy picture of investment and trade opportunities in China, before warning that Tibet and Xinjiang (where human rights atrocities are underway), Hong Kong (where the rule of law is being dismantled), and Taiwan (which Beijing has threatened to annex by force) are, quote, “red lines”. He made clear that Americans of all walks of life would do well to keep their mouths shut about these issues. Yang excoriated Trump Administration policies toward China and was unsubtle in pressing his audience to lobby the Biden Administration to reverse them.

Other senior Chinese diplomats made similar statements aimed at U.S. business people.

And General Secretary Xi Jinping, seated before a mural of the Great Wall of China, beamed himself to business elites in Davos in late January. He used his speech to enlist their support in resisting efforts by European and American policymakers to “decouple” segments of their economies from China’s. General Secretary Xi even wrote a personal letter to a prominent U.S. businessman exhorting him to, quote, “make active efforts to promote China-U.S. economic and trade cooperation….”

Now, in order to make clear that these were requirements by Beijing, not suggestions, Beijing squirted in a shot of vinegar in the form of sanctions announced on nearly 30 current or former U.S. government officials. These were on top of the sanctions Beijing had already placed on American human rights activists, pro-democracy foundations, and some United States senators last year.

Beijing’s intended message is: “If you want to do business in China, it must be at the expense of American values. You must meticulously ignore atrocities inside China’s borders; you must disregard that Beijing has reneged on its major promises—including its international treaty guaranteeing a “high degree of autonomy” for Hong Kong; and you must stop engaging with national-security-minded officials in your own capital—unless it’s to lobby them on Beijing’s behalf.”

The unmistakable ultimatum from Beijing is: “You have to choose.”

Another notable element of Beijing’s approach is its explicit aspiration to make the world permanently dependent on China’s manufacturing base, even as Beijing pursues independence from high-tech exports by European and American companies. In other words, decoupling is precisely Beijing’s strategy—so long as it’s entirely on Beijing’s terms. Beijing also has a deliberate strategy to remain the largest market for fungible commodities.

Please let it sink in for a moment: China’s top leader has stated plainly that he’s pursuing a grand strategy of making China independent of high-tech goods and services from advanced industrialized countries, while simultaneously making those same countries heavily reliant on China for its high-tech supplies and as a market for commodities.

What’s more remarkable is that the Communist Party is also no longer hiding why it is pursuing such a strategy. In a speech Xi delivered early last year, but published only last fall in the Party’s leading theoretical journal, Xi said China “must tighten international production chains’ dependence on China” with the aim of “forming powerful countermeasures and deterrent capabilities.”

This phrase—“powerful countermeasures and deterrent capabilities”—is Party jargon for offensive leverage. Beijing’s grand strategy is to accumulate and exert economic leverage to coerce its political aims around the world. I’ll give you a recent example: After cultivating significant trade volumes with Australia over the years, Beijing last year suddenly began restricting imports of Australian wine, beef, and barely for purely political aims. Beijing released a list of 14 “disputes”—in actuality, a list of political demands of the Australian government. The demands include rolling back Australian laws designed to counter Beijing’s covert influence operations in Australian politics and society; and they include muzzling Australia’s free press to prevent it from publishing news articles critical of China.

Australia’s travails are but a foretaste of what Beijing has in store for all of us if we fail to rise to the challenge.

CONSENSUS AND CONTINUITY IN WASHINGTON

What about Washington’s approach to China? President Biden last week published his Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, a 24-page document summarizing his priorities. The document makes clear that, as far as challenges to the United States go, China is in a category by itself. It is “the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system,” it states.

Secretary of State Tony Blinken, in his first major address (timed for the release of the strategic guidance), went further, describing the relationship with China as “the biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century.”

Secretary Blinken said “our relationship with China will be competitive when it should, be collaborative when it can be and adversarial when it must be.” He went out of his way to differentiate the Biden Administration’s approach from the softer policy of the Obama years.

But most striking of all is the degree to which the strategic guidance casts the U.S.-China competition in ideological terms. The document dwells on this theme. In his signed letter introducing the document, President Biden said: quote, “I believe we are in the midst of an historic and fundamental debate about the future direction of our world. There are those who argue that, given all the challenges we face, autocracy is the best way forward.... We must prove that our model isn’t a relic of history; it’s the single best way to realize the promise of our future,” end quote.

Now, Beijing’s dirty little secret is that Xi Jinping has been describing the competition in precisely such ideological terms for years in his internal speeches.

Take, for example, a key passage from General Secretary Xi’s seminal speech—kept secret for six years—to the Communist Party Central Committee on 5 January 2013.

“There are people who believe that communism is an unattainable hope, or even that it is beyond hoping for—that communism is an illusion.... Facts have repeatedly told us that Marx and Engels’ analysis of the basic contradictions in capitalist society is not outdated, nor is the historical materialist view that capitalism is bound to die out and socialism is bound to win. This is an inevitable trend in social and historical development. But the road is tortuous. The eventual demise of capitalism and the ultimate victory of socialism will require a long historical process to reach completion.”

The Biden and Xi quotations are almost mirror images of one another. President Biden’s quotation is, in effect, a belated American rejoinder to Xi’s secret call for the defeat of capitalism and democracy. Xi made that speech during President Obama’s first term!

American intellectuals and business lobbies have long resisted casting U.S.-China relations as an ideological struggle. President Biden’s guidance (like Xi Jinping’s) makes clear that, as far as policy is concerned, the matter is settled: The ideological dimension of the competition with China is inescapable—even central.

President Biden’s guidance also signals that while his tactics will deviate from the Trump administration’s, there is so far a significant degree of continuity in U.S. strategy. This is reflective of the bipartisan consensus on China that finally emerged over the last few years.

U.S. BUSINESSES, PREPARE TO GET WET

No wonder, then, that Beijing is focusing its influence activities on other segments of American society—the U.S. business community, in particular, but also state and local governments. Beijing knows that its influence efforts at the federal level are increasingly in vain: For the first time in decades, Chinese diplomats are facing resolve, rather than accommodation, on Capitol Hill and in two successive administrations in the White House.

So what should American CEOs do? First, they should come to grips with how much the situation has changed over the past few years—and that this change seems unlikely to be rolled back.

CEOs will find it increasingly difficult to please Washington and Beijing at the same time. President Biden’s strategic guidance flatly states that, quote, “We will ensure that U.S. companies do not sacrifice American values in doing business in China,” close quote.

And Chinese leaders, as I mentioned at the start, are issuing high-decibel warnings to multinationals that Western values are unwelcome if companies want to do business in China.

Like sailors straddling two boats, American companies are likely to get wet.

One prudent step would be for CEOs to undertake reviews of how the new geopolitical reality impacts their corporate-enterprise risk management on both sides of the Pacific. The great-power competition with China has introduced a thicket of new regulatory, fiduciary, and reputational risks that corporations are only just waking up to. Beijing’s intensifying use of extrajudicial tools adds a layer of personal security risk that businesses must weigh more heavily. Beijing’s taking as hostages two Canadian businessmen, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, is a case in point.

Another prudent step would be to draw up contingencies for diversifying supply chains. The rush to concentrate so much of the world’s manufacturing on the east coast of the People’s Republic of China in recent decades was an aberration, and an unsustainable one.

Now, no one in Washington is seriously threatening a wholesale decoupling of the two economies. That’s a strawman argument put forward by Chinese propagandists and a few alarmists here at home.

But decoupling of a more limited variety—particularly in key technologies—is already well underway. In the Trump Administration, we referred to this as “selective decoupling.” I’ve noticed that some Biden Administration officials use the term “managed decoupling.” Senator Tom Cotton and some others on Capitol Hill have adopted the term “targeted decoupling.” When so many different voices are using such similar language, it’s a sign CEOs need to pay attention.

ATTITUDE ADJUSTMENT

I said I’d close my remarks with a comment about the mindset I think we need to adopt in order for American democracy to pass “the biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century.”

A favorite metaphor in Beijing and Washington is that our countries are running a marathon, and only one contestant will prevail above all others. And it’s a fine metaphor. But let me posit that, right now, we are actually in a 400-meter dash that we must win in order to qualify for the next leg of the marathon. If, over the next four years, we fail to set the right conditions, with bold, affirmative policies, we could put ourselves on track to lose the marathon, though we might not realize it until several years down the line.

Above all, it will require us to consider in every policy we adopt, every bill we introduce, and each public-private partnership that government and U.S. industry undertake—whether each initiative increases American leverage in this competition, or surrenders leverage to a hostile dictatorship in Beijing.

The balance of the leverage, we shouldn’t forget, is heavily in our favor. It’s up to us to keep it that way.

Beijing knows that it is in a sprint right now, too. It knows better than anyone that the advantages of a centrally planned system are fleeting, and that the economic shortcomings of such as system—including waste, bureaucratic inertia, and the unforgivingly magnified consequences of each miscalculation—will start to show before too long, if they aren’t already.

Beijing is trying to engineer victory from the mind of a single leader; free societies like ours, by contrast, harness the human spirit. And therein lies our advantage.