- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

Editor’s note: This essay is based upon a forthcoming book by the author, War by Other Means.

In the past five years, the conventional wisdom in Washington has been that the U.S. State Department is dramatically undernourished for the work required of American civilian power abroad. Since 2000, there have been a staggering number of think tank reports advocating a more robust diplomatic corps. The last three Secretaries of State and the last two Directors of the U.S. Agency for International Development have not only had ambitious goals for improving their departments, they have actually received the money to make improvements. Congress has increased funding to the Department of State and the U.S. AID by 155 percent since 2003, and the size of the diplomatic corps has grown by 50 percent since that time.

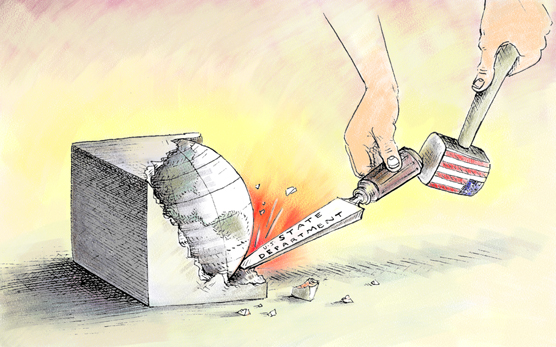

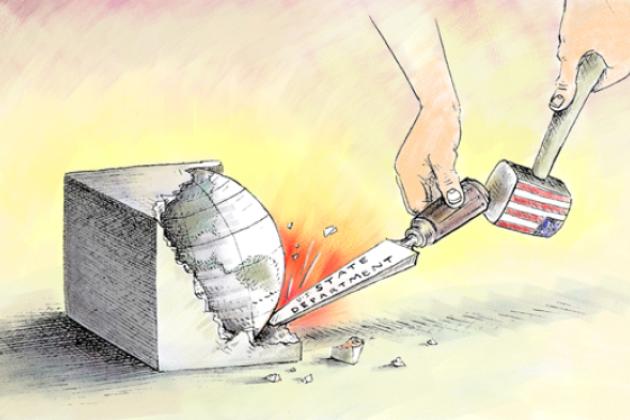

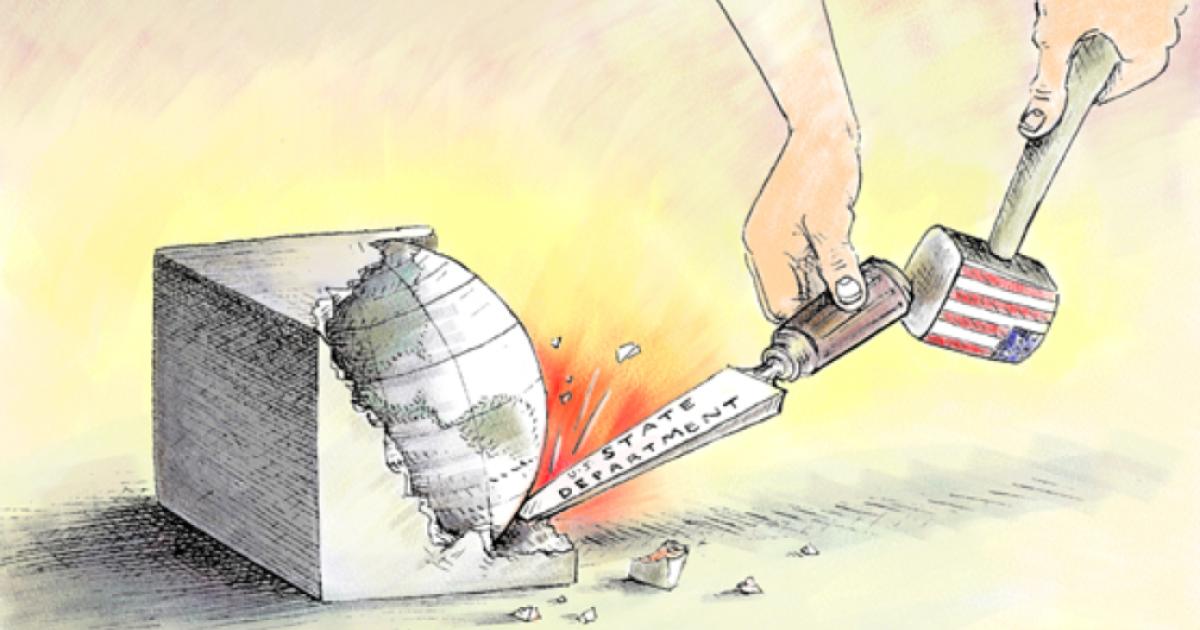

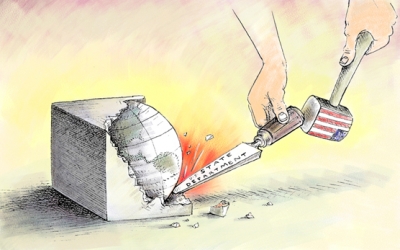

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Yet practically no one believes that the U.S. Department of State is currently performing at an adequate level. There are no voices arguing that it is the diplomatic equivalent to the dominant American military. Even sympathetic observers like the Stimson Center—a think tank devoted to global security—conclude, "today’s Foreign Service does not have to a sufficient degree the knowledge, skills, abilities, and outlooks needed to equip career diplomats to conduct twenty-first-century diplomacy." Despite the substantial increase in the department’s workforce, it continues to contract out work that is mission-critical or the function of which is inherently governmental.

The State Department has a better record than it gets credit for, certainly. It established twenty new embassies in Europe after 1991 without additional personnel, and the diplomats who have joined the Foreign Service since 2001 are much more likely to want to deploy to Provincial Reconstruction Teams in Iraq or Afghanistan and to change the world for the better rather than remain safely ensconced in embassies and report on changes occurring.

Still, the Department of State underperforms, both for what the country needs, and for the resources it has. Foggy Bottom emphasizes that all parts of government must work together. Yet the department remains—even by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s own assessment—inadequate to the task.

If further proof of the department’s inadequacy were needed, it is that major swathes of activity that are civilian in nature continue to migrate to the military. The militarization of American foreign policy does not reflect an ambition by the military; it reflects the vacuum left by inadequate civilian power. Work needs doing, and the Department of State remains incapable of doing it. The most recent example would be governance issues in Afghanistan: small unit military leaders rather than diplomats are working to create local councils throughout the country, and the military command has just established a high-level anti-corruption task force—two activities that should have been carried out by civilians. But despite an embassy of over a thousand civilians in Kabul, those tasks remain in the hands of the military.

The militarization of American foreign policy is bad for our country.

The most fervent advocates of a more vibrant American diplomatic corps are found in the American military. Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Admiral Mike Mullen have been the apostles of greater State Department funding, routinely advocating for it publicly to the Congress, and within government counsels.

Bringing the Pentagon’s sensibilities to the problems of improving American diplomacy sheds light on why the State Department has not been more successful. The Department of State is deficient in two crucial areas in which the Department of Defense excels: education and programming. Adopting the Defense Department’s attitudes and commitment to these areas may prove more valuable to State than any additional money defense leaders could help it attain.

The employees of the State Department are among the American government’s most talented. They come into the diplomatic corps with, on average, a graduate education and eleven years of prior employment before joining the Foreign Service. The Department of State proceeds to make very little out of a lot by not investing in the kind of professional education and training that will continue to make our diplomats successful for the demands they face as their careers progress. The people who are successful in the State Department are people who can be thrown in the deep end of the swimming pool and not drown; but the department never teaches them to swim, and the most successful diplomats even come to discredit the value of training because they succeeded without it.

In the past seven years, Congress has authorized three increases in staffing levels in order to build time into diplomats’ careers for education and training: Secretary of State Colin Powell’s Diplomatic Readiness Initiative in 2003 and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s Transformational Diplomacy Initiative in 2006 are two examples of such programs. Secretary Clinton has also requested and received additional Foreign Service and Civil Service positions.

Yet none of these substantial increases in personnel resulted in more professional education and training for diplomats, nor did they build time into their career tracks to participate in such programs. Training remains either a voluntary (off-duty) activity or something the Department’s most valuable people are not freed up to participate in. Secretary Powell made mandatory some valuable leadership training, but there has been no major effort to develop a core curriculum of knowledge that diplomats need at different thresholds in their careers, or a process developed by which diplomats are incentivized and rewarded for undertaking it.

We can and should strengthen our civilian power.

It merits mention that even the most starry-eyed believers in leading through civilian power assess the cost to produce a better diplomatic corps as minimal. These advocates are not arguing to double or triple the budget, they are arguing for marginal annual increases. For instance, the Stimson Center’s "Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future" is one of the most functionally ambitious and carefully accounted studies of increased funding to the State Department—and it concludes that the price of meeting all of the State Department’s needs is only $3.3 billion across four years. Such a sum amounts to roughly a 1.5 percent increase in the department’s $52.8 billion operations budget per year. That is a small number even before you compare it to the $671 billion budget request of the Defense Department for 2012.

Two conclusions leap out from this fact: first, it would take a pathetically small amount of money to fully meet the stated funding needs of the diplomats; and second, that if the State Department believes its performance can be so vastly improved on such a thin margin of additional resourcing, they probably have very little idea what it would take to actually make themselves a successful organization.

It is tempting just to give the State Department all the money it needs and hold it accountable for producing the dramatic improvements in performance that its advocates believe are just barely out of reach. But the Department of State lacks the rigorous culture of program analysis and evaluation that exists at the Department of Defense. That culture provides the Department of Defense with a much stronger basis for advancing and defending its spending requests within any administration and to the Congress. It is arguable that the second most powerful person in the Department of Defense is not the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, but the comptroller, who develops and defends the budget. Until 2009, the Department of State didn’t even have a parallel figure.

Perversely, the chronic underfunding of the Department of State has created a vague budgetary culture there. One would think that scarce funds would foster careful expenditures and transparent accounting. But just the opposite is true. The State Department has a terrible reputation on Capitol Hill for pulling rabbits out of its budgetary hat—presenting budgets that do not add up—instead of carefully costing and tracking programs in ways that would build Congressional confidence in the ability of the organization to manage larger budgets. For State to achieve the kinds of sustained budget increases that advocates of stronger civilian power seek, it will need to develop a long-term budget perspective and the ability to prioritize its activity to make better use of the resources it gets.

Imagine a State Department that actually leads American foreign policy…

The militarization of American foreign policy is bad for our country. We can and should strengthen our civilian power. But the State Department has not proven capable of identifying or redressing its inadequacies. The department’s recent annual "Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review" (QDDR) claims to pose the question "how can we do better?" and answers "by having more money and more senior positions." But resources cannot be the answer, given the influx of money State has received in the past decade. If money, or lack of funding, were the problem, then the problem would have been solved long ago.

The Department of State must develop the means of assessing activity so that it can make a credible case that money spent on civilian power is a better investment than other alternatives. State must earn a position of leadership by demonstrating the intellectual and operational proficiencies that will draw adherents. Credibility begins with demonstrating excellence and asking for it to be rewarded once achieved. Instead of surveying its own ranks (as the QDDR did), State should throw itself open to consumers of its services, like other national security agencies, policy makers, members of Congress and their staffs, Americans traveling abroad, etc. It should administer consumer satisfaction surveys that would inform its priorities and resourcing.

Imagine a State Department that actually leads American foreign policy, a department whose ideas for shaping the world in positive ways drive the agenda of this nation’s engagements abroad. It would be a department that builds a broad basis of public support to which elected leaders would respond, a department whose data drives public and Congressional analyses of problems and programs and whose diplomats are so expert that they are journalists’ preferred interviews, major universities’ preferred hires. This would be a department that is a magnet for entrepreneurial people of diverse skills, putting those skills to creative use, fostering professional growth. This is a department where competition for staff retention is so fierce that it drives a personnel pyramid wide at the base, a department with an educational program so rigorous it equips our diplomats to succeed at every level of their careers. Its personnel policies would identify emergent needs and incentivize activity rather than description. Its senior leadership would be so proficient and command activity so expansive that the Pentagon would seek to place four-star generals as deputies to our diplomats rather than give diplomats consolatory slots in our military headquarters.

We should not just imagine such a State Department—we should demand it. And we know how to achieve these goals; after all, we do so in the military and in American businesses every day. Why, then, do can we not empower a thriving State Department, on which the success of our military efforts depend? The State Department and the Obama administration must create a more solid basis for a civilian-led American diplomacy.