- US

- Contemporary

- World

- Law & Policy

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- History

Modern terrorists usually attack the citizens and interests of relatively rich, open societies. It might be that they object to the far-flung foreign interests that richer countries have and seek to protect, or that they expect to have greater impact where public opinion is freely informed, or both. Many studies of modern terrorism reflect the same bias, partly because richer, more open societies can provide scholars with more of the data necessary to build and analyze case studies.

It is interesting to find a rare case of terrorism and counterterrorism that documents the opposite: an outrage that was perpetrated within a closed society, immediately smothered by strict censorship, and investigated and brought to trial under a blanket of secrecy. This case is unexpectedly revealing about terrorism, counterterrorism, and the relative strengths of open and closed societies.

The case is based on files of the Lithuanian KGB that were recently acquired by the Hoover Archives. These records are interesting for two reasons. First, Lithuania was a front line of the Cold War: a strategically sensitive border state with a history of anti-Soviet nationalism, dense commercial and family links with foreigners, and an open coastline. Second, while access to the central KGB archives in Moscow remains virtually impossible, the Lithuania collection at Hoover can be used as a window into the KGB and its role in Soviet politics and society. The story examined here is one of many that can now be told for the first time.

MYSTERIOUS ATTACKS, CONFUSED PURSUIT

In Moscow, January 8, 1977, was gray and frosty. It was Saturday, two days after the Orthodox Christmas and three weeks after Leonid Brezhnev’s 70th birthday. At 5:33 p.m., a bomb exploded on a packed train between the underground Izmailovo and May 1 stations. It was followed within forty minutes by two more explosions. At 6:05 p.m., a second bomb was detonated at food store number 15 in the Bauman district. The third went off in the street between Red Square and Lubyanka Square, the KGB headquarters, at 6:10 p.m.

These attacks came out of the blue. No warning was given, and no one claimed responsibility. Two days later, on January 10, the Soviet news agency TASS issued an uninformative bulletin that mentioned only the subway blast. Without giving numbers, it recorded that “the injured received medical assistance.” In fact, the bombs were deadly: there were forty-four casualties, including seven killed. In London the “journalist” and unofficial KGB spokesman Victor Louis suggested that Soviet dissidents could be to blame. On behalf of the liberal opposition, the Nobel peace laureate and academic Andrei Sakharov immediately rejected the use of violence, adding that he could not rule out a KGB provocation. In the months that followed, the only visible police activity was persistent harassment of Sakharov and his circle.

Behind the scenes, the KGB mounted an intense nationwide hunt for the perpetrator, code-named “Blaster” (Vzryvatel’ or Vzryvnik). Where might Blaster be found? At first agents had no idea where to look, so they looked everywhere—including Lithuania.

There were few clues. A circular issued on behalf of Lithuanian KGB chief Juozas Petkevičius, dated March 23, details the few facts that emerged from the crime scene. There were many witnesses to the attacks but no picture of the perpetrators—only a vague description of a tall, broad-shouldered man in a brown overcoat with a beaver collar and fur hat, who pushed aside customers in the food store and rushed into the street.

Of more practical use was forensic reconstruction of the bombs from metal fragments embedded in the surrounding structures and victims’ bodies. The pipe that contained the subway bomb originated most likely in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov (today, Kharkiv). It had been welded using specialized equipment possibly associated with military metallurgy. Equally important was the recovery of artificial leather from the bag used to conceal the bomb. The fabric was of a type manufactured in the district of Gorkii (Nizhnii Novgorod). After manufacture, however, the materials were widely distributed to dozens of plants across the Soviet Union, including Lithuania.

The Lithuania collection at Hoover is a rare window into the KGB’s role in Soviet politics and society.

The March 23 circular did more than list facts. It also reported complaints about the detective work in Lithuania by the local KGB operatives and their agents. This proved to be the first of a litany that rose in volume until the search was concluded.

The source of anxiety was quality assurance. The KGB was already rounding up its “usual suspects” for questioning. Questions were being asked, but the answers were giving too few leads that could be passed back up the chain of command for further investigation. Regional KGB leaders worried that the rank and file were going through the motions of a manhunt but no more than that. If the questions had been asked, the boxes could be checked and the plan fulfilled, regardless of whether the answers were contributing to real progress. Unlike most Soviet civilian employees, KGB officers were highly selected for political loyalty and personal self-discipline, but they too could pretend to work, as in the joke “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work.” In this episode, quality control seems to have been as much a problem for the KGB as for Soviet managers of industry and other economic enterprises.

KGB leaders responded with a typical Soviet-era program of enforcement and verification. They emphasized the atrocious nature and political importance of the original crime. Aiming at the rank-and-file agents, they re-profiled the usual suspects in greater detail, listing numerous markers that should draw suspicion and prompt deeper investigation. Aiming at middle KGB managers, they designed new reporting forms and demanded tighter compliance with deadlines, including accounting for negative results that would both eliminate suspects and demonstrate tasks completed.

Thus, the KGB circular of March 23 listed these for special attention: Lithuanian visitors and residents who could be shown to have visited Moscow over the critical period; released prisoners; any who had complained to the authorities without success about unsatisfactory living conditions, dismissal from work, refusal of an exit visa to travel abroad or emigrate, or denial of access to secret documents (necessary for a vast range of white-collar employments); and all with experience of or access to various specialized technologies and materials used to make the bomb (explosives, detonators, welding equipment) or carry it (artificial leather and personal accessories).

After the bombings, the only visible police activity was persistent harassment of Andrei Sakharov and other dissidents. But behind the scenes, an intense nationwide manhunt was under way.

A follow-up circular of July 21 issued a model questionnaire for KGB officers to distribute among auxiliaries, agents, informers, and reserve officers, detailing markers of suspicion. Listed for closer study was anyone previously convicted of crimes against the state or expressing hostility to the Soviet system or showing tolerance of anti-Soviet and nationalist views; dissatisfied complainants; dissidents and “Zionists”; anyone with a mental illness; and anyone with access to the materials or equipment involved in the bomb making. The July circular stressed that the KGB was not necessarily looking for just one person; the bomber could have worked alone, or one person could have made the bomb and another placed it.

A CONSPIRACY WITH “POLITICAL IMPORTANCE”

By late summer, the KGB leadership was in a state of high nerves. On August 19, Lithuanian KGB deputy chief P. Voroshilov circulated a wide-ranging critique of the work done so far. Not all officers, he observed, had grasped the “political importance” of the matter. He complained that the search was being carried out in a general and abstract way, with deficient reporting and missed deadlines. In particular, he said, too much emphasis had been put on whether individual suspects could be placed physically in Moscow on the crucial date, at the expense of other lines of inquiry that might expose a conspiracy with not all present at the scene of the crime. As a result, there were still too few leads.

Moscow visitors, released prisoners, anyone who had complained about living conditions, employment, revoked security clearance, exit visas—all these and more were potential suspects.

Voroshilov demanded that from this point on the search must be given “first importance.” All investigations and agent contacts, however routine, including vetting and recruitment, must explicitly consider the possible identification of Blaster; all negative results must be documented.

At about this time, an alert KGB officer at Tashkent airport made the first partial breakthrough. Among passengers with hand luggage, he spotted a bag similar in fabric and design to that forensically reconstructed from the Moscow bombings. It turned out to have been on sale in Yerevan, the capital city of Soviet Armenia, beginning on December 15, 1976, only three weeks before the terrorists struck in Moscow. There was an Armenian connection.

Could there be an Armenian connection with Lithuania? On August 23, Voroshilov circulated a photograph of the bag. He ordered a new search to sweep up Lithuanian residents who had visited Armenia at the crucial time for work or recreation, or had had family or legal or illegal business contacts with Armenian residents, with a particular focus on any who might have bought bags in Yerevan for personal use or resale.

The scale of activity in Lithuania, a country of around 3 million people, is captured statistically in a summary of work done up to the end of August. Looking for Blaster were 198 agents (not including the KGB staff officers, called “operatives”), 126 “trusted persons,” 9 auxiliary workers, 17 reserve officers, and even two KGB residents abroad. From currently active cases, 98 people had been screened. These were classified as follows:

- “Previously convicted of especially dangerous state crimes,” 11

- Currently under investigation and verification, 9

- “Extremist-inclined Zionists,” 2

- Interviewed in connection with “hostile expressions, negative attitudes to Soviet actuality, and other motives,” 32

- Dissatisfied complainants, 4

- Mentally ill with aggressive inclinations, 6

- “Being processed according to primary documents in secret files,” 18

- Working or having worked with explosives, 8

- Known to have flown to Moscow on January 7–8, 8

The report lists additional measures that testify to the intensity of the manhunt: for example, the Lithuanian KGB agent network was currently searching for all who had left work, moved house, or been imprisoned for a trivial offense after January 8; all who had served in the army, worked with explosives, and been dishonorably discharged; and all who had traveled to Armenia in December or January.

Although the investigators had narrowed their lines of inquiry, after nine months they still had no idea exactly whom they were looking for. In the end, the perpetrators gave themselves away.

THREE ENIGMATIC SUSPECTS

Late in October, a routine police patrol interrupted one of them as he tried to prime and place a shrapnel bomb in the crowded waiting room of Moscow’s Kursk railway station. He walked away, leaving the bomb, which was recovered intact. With the bomb were personal effects intended for destruction. These helped quickly identify the terrorists.

Taking the express train from Moscow, Zaven Bagdasarian was detained as he left it in Yerevan. Another passenger on that train, Akop Stepanian, was arrested shortly afterwards. These were the perpetrators, but they did not look like the leaders. A short trail led to a third man, Stepan Zatikian. A house search found material evidence linking him directly to the January bombings.

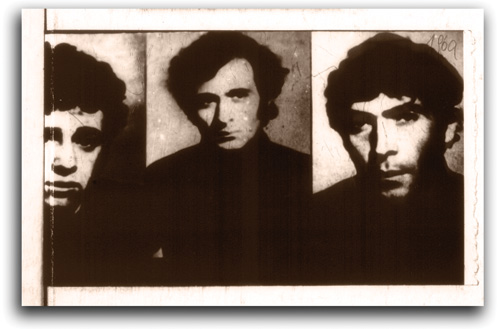

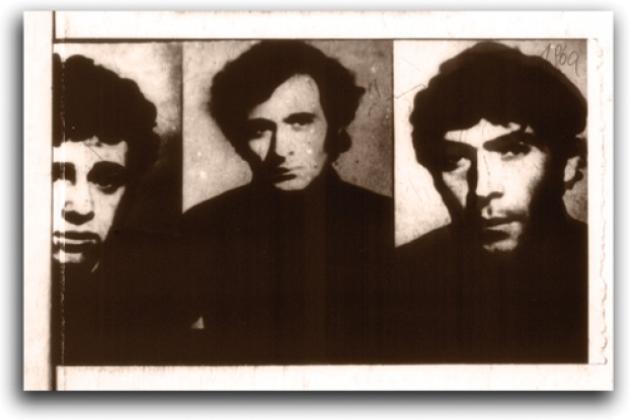

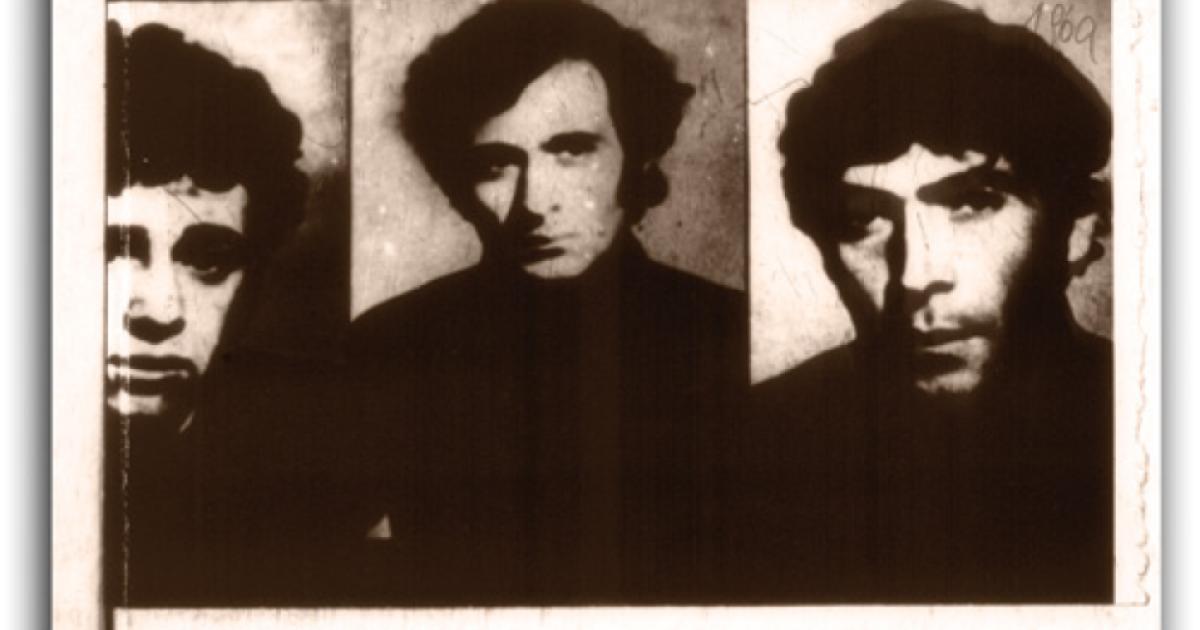

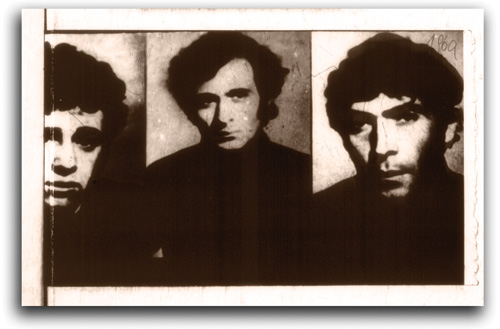

Microfilmed images from a KGB dossier show, left to right, Akop Stepanian, Stepan Zatikian, and Zaven Bagdasarian. The Armenians were arrested in the three 1977 Moscow attacks after a fourth, failed bombing attempt in a railway station. The evidence has never been published.

At this stage, nothing was made public. But news of the arrests spread quickly through secret KGB channels, reaching Vilnius, Lithuania, in a few days.

The three accused were men of similar age. Zatikian, a metalworker, married with two children, and Stepanian, a welder, single, were 31 and 30, respectively; Bagdasarian, an unemployed decorator, also single, was 23. While Bagdasarian, allegedly “heavily influenced” by the first two, had a clean record, Zatikian and Stepanian were already known to the Armenian KGB. Zatikian had previously served four years in the Dubrava labor camp and Vladimir prison for taking part in an organized nationalist group, the National Unification Party of Armenia. This party demanded a plebiscite on Armenia’s independence from the Soviet Union, and unification with the Armenian lands in Turkey. After his release, Zatikian had tried to renounce his Soviet citizenship and claim asylum at the U.S. embassy in Moscow. As for Stepanian, the Armenian KGB had previously interviewed and warned him concerning his nationalist attitudes—clearly without achieving the desired effect.

It seems likely that the Armenian KGB had not previously identified either man as a suspect. Archives of the civil rights and historical organization known as Memorial record that the KGB had taken Zatikian in for questioning only weeks before his arrest but did not raise his possible implication in bombs and terrorism during a twelve-hour interview.

The Lithuanian KGB chief complained vigorously about agents suspected of just going through the motions. He could be in deep trouble if the bombers were on his turf and his agents failed to catch them.

The roots of the affair clearly lay in Yerevan. In Lithuania, however, there was still work to be done. At the end of November, Petkevičius ordered a renewed search for evidence that the conspirators might have visited Lithuania or had contacts there. Vladimir and Dubrava were far from Lithuania, but Lithuanian convicts had been confined in both places; had Zatikian acquired contacts among them? Given Lithuanians’ many foreign connections, could the conspirators have met with foreigners in Lithuania? Petkevičius also ordered an alert against further acts by possible accomplices not yet identified. On the same day, he joined with the Lithuanian minister of the interior to demand that the investigation so far be checked, audited, and rechecked if necessary.

The men were tried in secret. According to subsequent reports, Bagdasarian admitted the charges in whole and Stepanian in part. Zatikian, who had not been traced to the crime scenes but was implicated by other evidence, denied everything, rejecting the authority of the court and the legitimacy of the “Jewish-Russian state.” The guilty verdict and death sentence were delivered on January 24, 1979. There was no appeal. The men were executed five days later. The evidence that convicted them, although extensively leaked, was never published. The documents available describe the evidence, assert the men’s guilt, and make it likely on a historian’s balance of probability, but do not prove it beyond reasonable doubt.

The world heard nothing until January 31, 1979, when a short bulletin announced that three men had been tried in the USSR Supreme Court, condemned to death, and executed. Only Zatikian was named. At the time, Andrei Sakharov protested that secret justice was no justice. He and other dissidents suffered a renewal of accusations, threats, and intimidation. Soviet Armenia remained quiet.

THE POLICE STATE’S BURDEN

We remain unsure that the three accused men were properly convicted. Assuming they were, how well did they fit the general profile of a terrorist group? Specifically, if Armenian nationalists carried out the Moscow bombings, why did they not announce their existence, claim responsibility, or make demands of the Soviet regime?

Nine months of frenetic investigation proved fruitless. In the end, the perpetrators gave themselves away.

Surprisingly, such reticence is typical of modern terrorism. Stanford University political scientist Max Abrahms has observed that since 1968, “64 percent of worldwide terrorist attacks have been carried out by unknown perpetrators. Anonymous terrorism has been rising, with three out of four attacks going unclaimed since September 11, 2001.” Such puzzles do not fit the standard model of rational agents using terrorism to achieve political ends, argues Abrahms, who says another model solves the puzzles: terrorists are often better understood as people who rationally use terrorist activity to achieve strong affective ties with other terrorists.

The Zatikian group fits into this second model. Men in late youth, two of them single, the conspirators had their closest social bonds with each other. Perhaps they conspired to kill others to cement their friendship. Seeking publicity would not have helped them to do this, so they did not seek it.

Sakharov initially speculated that the KGB had organized, provoked, or exploited the bombings to go after selected scapegoats such as democratic opponents of the Communist Party. Does the evidence bear this out? The KGB certainly exploited the incident to detain, interrogate, and otherwise harass some dissident intellectuals, but eventually these were released.

In other ways the Lithuanian KGB search looks genuine. Regional leaders mobilized the entire agent network for the widest possible search, and took action when they found signs that the search was becoming perfunctory. The Lithuania documents certainly start from the “usual suspects,” but they do not convey a plan to implicate them regardless of the evidence. On the contrary, regional KGB leaders seem to have been as eager to eliminate suspects as to find the guilty. Their apparent concern for reaching evidence-based conclusions is in marked contrast to the foot-dragging and lack of diligence that they identified among their own rank and file.

KGB leaders in any region, including Lithuania, faced several possibilities, some of which must have provoked immense anxiety. It would be bad for Lithuanian KGB chief Petkevičius if he found the guilty in his home region, because he would then have to explain how he had failed to stop an attack on the state. If they were found outside Lithuania, this would become someone else’s problem. In fact, it would advance Petkevičius’ interests most if his investigators could provide the evidence that pointed somewhere else. But if the guilty were in fact inside Lithuania, Petkevičius could not fail to look for them—it would be imperative that his own men find them first. The very worst outcome: investigators from another region, or Moscow itself, come into Lithuania and find them under his nose. To their horror, this is what happened to the Armenian KGB leaders.

The case of the Armenian bombers tells us something about secrecy. In one well-established view, terrorists breathe what Margaret Thatcher called the “oxygen of publicity.” (This, however, relies on the belief that terrorists always stage their atrocities for maximum public impact, the kind of events we are most likely to hear about and remember.) In 1977, the Soviet authorities had the advantage of rigid censorship and a ban on unofficial media to deny terrorists that oxygen and so prevent terrorist attacks. Did it work?

Not well. Censorship ensured that the original outrage received almost no publicity. But the Moscow bombers did not seek publicity and made no attempt to issue warnings, demands, or claims of responsibility. Lack of publicity did not stop them from trying to continue their campaign. It did prevent most ordinary Moscow residents from being aware of the threat. If censorship achieved anything else, it was perhaps the prevention of copycat attacks in the years that followed.

While the KGB certainly used the bombings as a pretext to harass dissidents, in the end they were released. From the very start, the secret police showed a commitment to look beyond the usual suspects.

Sakharov was right: secret justice is no justice. In due course, this became a source of weakness of the Soviet police state. Could Armenians ever be sure, for example, of getting a fair trial in a Russian court? Such calculations did not cause, but may well have increased, the readiness of Armenians to embrace independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.