- Budget & Spending

- Economics

Social security presents President Obama and Congress with a daunting policy challenge. The program currently faces both worsened near-term finances and a large long-term deficit. There is good reason to enact a correction soon, for solutions become less palatable with each year of delay.

Americans care deeply about Social Security, which is possibly the nation’s most cherished domestic program. One might naively assume that political rewards would accrue to elected officials who accept responsibility — and credit — for strengthening the program’s finances. But policy makers face a further challenge, in that not only are Americans sharply divided about Social Security policy choices, but they are divided even about the underlying facts and the problem to be solved. Despite years of bipartisan efforts to objectively define and quantify the Social Security financing challenge, consensus agreement even on basic factual predicates remains elusive. An equitable solution will be unobtainable unless elected leaders bring stakeholders together around a common understanding of the facts and the need to take reformative action.

Social Security is fully able to meet today’s benefit payments. Although the program is now running cash deficits, no one is seriously worried about whether current payments will be interrupted. But the trends that threaten Social Security’s future have begun to be felt and will intensify sharply in the coming years. In a perfect world, this challenge would be easily understood. Social Security financing is one of the easiest issues in all areas of federal policy to grasp, once it is shorn of superfluous detail. But arcane concepts such as “solvency,” “actuarial balance,” and Trust Fund accounting can make a simple problem seem very complex.

In reality, it is not at all complex: More people are now heading into retirement than ever before and stand to collect larger benefits for a longer time. This means higher costs facing our children and grandchildren than previous Americans were ever asked to shoulder. And, despite some misrepresentations to the contrary, the government has no credible plan for financing these growing costs. In addition, the longer we put off dealing with Social Security, the less fair the solution will be. Action today could render the current system permanently sustainable without changing benefits for those now in or near retirement, without raising taxes, and while allowing future retirees to receive higher benefits than today’s (even relative to inflation). Within a few years this will no longer be true. At that point, we’d need either to tell young Americans that their taxes are going up or future retirees that their standards of living are going down.

Action on Social Security, perhaps more than on any other issue, is paralyzed by conflicting views of underlying facts. Many of these conflicting interpretations are driven by misunderstandings of the 1983 program reforms. That legislation placed a layer of confusion over program finances, and engendered a further tendency toward gridlock in what was already an intensely polarizing issue. Before 1983, there existed profound disagreements about Social Security policy choices, but general agreement on the state of program finances. Today, there is widespread disagreement on both. This has had a paralyzing effect on our capacity to agree on adjustments to Social Security policy, and has perpetuated confusion that will fatally undercut future legislative discussions until it is untangled.

To understand the choices now before us, it’s useful to know what happened in 1983, why it did, and how the result has led to sharply divergent views of program finances today.

How we got here: The 1983 amendments

The 1983 social Security reforms achieved much that is praiseworthy. The reforms, a combination of tax increases and restraints on benefit growth, averted what was previously projected to be imminent program insolvency. They were built with a prudent margin for error, in case the projections were wrong (some of this cushion was in fact needed). They accomplished sound financing of Social Security for decades to come. All of this deserves our recognition and respect.

The political legacy of the 1983 reforms, however, has been destructive. Indeed, much of the confusion surrounding the current Social Security debate is directly traceable to decisions made decades ago. Throughout the Social Security reform effort of 1981–83, both Republicans and Democrats knew there was a problem and that it was coming fast. The key players all understood that prompt action was needed to save Social Security. But even with that shared appreciation, such action nearly didn’t happen.

The essential clarity was fostered by a shared understanding of how Social Security worked. Both sides understood that benefits were financed by taxing current workers. If annual taxes were insufficient to fund benefits, a problem obviously arose. There was indeed a Trust Fund then, but its balances were deliberately kept small and it was not expected to carry the program through extended periods of significant cash shortfalls. Indeed, so little credence was then given to the Trust Fund as a meaningful source of pre-funding for future benefits that its assets were not even included in measures of Social Security’s future actuarial balance. Many now wrongly assume that the crafters of the 1983 legislation deliberately intended to depart from this historic practice, and that they purposely built up a significant Trust Fund to pre-fund a portion of the baby boomers’ benefits. Given the substantive consequences of the reforms, this is an understandable misperception. The historical record is clear, however, that no such pre-funding has actually occurred and indeed that there was no such intent. Today’s large Trust Fund was actually an unwitting byproduct of the 1983 reforms — and, equally, an unwitting destruction of the shared analytical clarity that had made those reforms possible.

According to the 2010 Trustees Report, Social Security faces a cash deficit this year and next. These deficits are expected to briefly disappear, then to resume in 2015, when they will become permanent and grow dramatically. By 2020 they will be larger, even relatively, than those experienced in the program’s “crisis” years of 1977 and 1982. Yet many believe that there will be no problem until decades down the road, in 2037. Why? The answer lies in the Social Security Trust Fund, whose large current balance was facilitated by the 1983 reforms.

Before we dissect the Trust Fund, it’s important to understand that even if there were no financing problem until 2037, this would in no way imply that reforms should be deferred until that date. Allowing the full cost of correction to fall on those unlucky system participants in 2037 would then mean either a 22 percent reduction in their benefits — for both new and previous retirees — or a sudden increase in taxes on workers to 16.1 percent, or something in between those two scenarios. As previously noted, a solution enacted today could avoid such tough choices between rising taxes and declining benefits. The later we act, the harsher someone’s sacrifices will be; the earlier we act, the less any one individual or group will feel the consequences. No one should therefore confuse the projected insolvency date with the date demanding action.

Recognizing the immediacy of our challenge does not mean, as some have sensationally suggested, that the government would in effect renege on the bonds in the Trust Fund. Despite Social Security’s current cash deficit, no serious advocate is suggesting that the benefits of today’s seniors be suddenly cut. Nor do reform proposals fail to redeem the Trust Fund’s debt. These bonds will be honored; we must, however, recognize that their existence doesn’t substitute for a sensible plan both for the Trust Fund’s redemption and to bring Social Security into financial balance.

The persistent opinion that there will be no problem until 2037 is fueled by misunderstanding of the 1983 reforms, and it is usually expressed in arguments that fall into four categories:

The full faith and credit argument. This first such argument is simple (and weak): The Trust Fund can be relied upon because it is invested in Treasury bonds, arguably the safest investment in the world. Were matters so simple, then solving the Social Security shortfall would be easy: We could simply issue $16.1 trillion in bonds to the Trust Fund and declare the problem solved forever. One need not think very deeply to realize, however, that this sidesteps the critical question: Where will the money come from to pay off these bonds when they come due? We can choose to issue more bonds to Social Security at any time. But doing so doesn’t create the resources to pay Social Security benefits.

The storehouse of saving argument. Some assert that Social Security, by running surpluses for several years, has been a storehouse of saving. Because the government was able to borrow and spend Social Security money for the past few decades, so this viewpoint holds, it was able to reduce the amount of borrowing it would otherwise have done to finance its spending. Academic analyses have fairly consistently shown, however, that Social Security surpluses have not been used to reduce overall debt but instead have induced additional government consumption. Wharton economist Kent Smetters found that the presence of program surpluses actually reduced saving, by inducing legislators to spend more in amounts greater than the surplus. Other papers have reported similar results. The view that the Trust Fund represents real saving is generally inconsistent with the best empirical analysis.

The social justice argument. Some have argued that because Social Security is self-financing, it does no harm for it to run large surpluses in some years and large deficits in other years, as long as these balance out over time. Advocates of this view sometimes even regard the deficit years as desirable, because in those years a progressive income tax would subsidize a regressive payroll tax.

This may sound reasonable at first until one thinks it through. It overlooks that different generations pay taxes and receive benefits at different times. When this is considered, the “social justice” rationale for Trust Fund financing disintegrates.

To understand this, consider a simple analogy of a family with its own retirement fund. Everyone in the family agrees to put money into the fund while working, and each is to withdraw benefits in retirement. Now let’s assume that the father spends from the fund during his working years. Each time he does so, he puts a note in the fund promising that it will be repaid in the future. When it is time for the father to retire, he tells his son, “Son, I’ve spent all the money in the fund on other things I wanted. But now I am ready to claim my benefits, so it’s time to pay the fund back. So, in addition to the contributions we previously agreed on, you’ll need to come up with additional contributions to pay back the money I spent.” Obviously, the son would be none too pleased by this arrangement. It would not escape his notice that the person who borrowed the money (the father) is not the same person being asked to pay it back (the son).

This is the flaw in the “social justice” argument. It neglects an enormous intergenerational income transfer that occurs when an earlier generation spends Social Security money on other wants, while a later generation must pony up additional revenue to redeem the trust fund — indeed, to pay benefits to that same older generation. Only if the trust fund had initially facilitated saving would its repayment actually balance the scales.

The 1983 intent argument. Many who recognize that there has been no fact of saving nevertheless argue that there was an intent, a societal compact, to pre-fund the baby boomers’ retirements through a large Trust Fund buildup. One recent publication of the National Academy of Social Insurance, for example, asserted that the coming period of Social Security deficits was “precisely what the 1983 reforms intended to happen.”

This belief is very widely held. It’s also very false.

The existence of the conviction is unsurprising. After all, the singular feature of the 1983 reforms is the pattern of large surpluses and subsequent deficits they engendered. Surely, it is assumed, such a consequential outcome must have been intentional. Why else would the 1983 negotiators have done this, unless they believed that the near-term surpluses could be banked to finance long-term deficits? The evidence instead shows that not only has the Trust Fund not been saved, but the framers of the 1983 amendments never planned for it to be. Neither the Greenspan Commission nor members of Congress recognized during their deliberations that the reforms would produce decades of large surpluses, and they would not have regarded such a result as desirable or effective pre-funding had they known.

The evidence is extensive. Greenspan Commission member Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan later asserted that the resulting surplus “has come upon us almost unawares.” Social Security Subcommittee Chairman Jake Pickle, who played an active role in moving the 1983 legislation, then stated flatly that “We would not want to fund our national retirement program other than on a pay-as-you-go basis.” Multiple statements by commission Executive Director Robert Myers document that there was no intention to depart from pay-as-you-go financing. Of course, the perspectives of individuals are fallible. But the other documentary evidence tells the same story.

The Greenspan Commission did not report a single complete plan to Congress, and thus could not have provided an analysis of annual cash flows for any such plan. Instead, it delivered recommendations for provisions to close roughly two-thirds of the projected solvency gap on average, and left it for Congress to choose among options to fill in the remaining third. Nowhere in the commission report is there a comprehensive plan analyzed for its effect on annual Trust Fund balances. During its deliberations, the commission reviewed memoranda describing each option’s near-term effects under both intermediate and worst-case scenarios, and its long-term effects on average under intermediate projections. The annual flows over the long term under different policies are not presented on those memoranda.

The commission’s prudence in ensuring that near-term insolvency would be averted in a worst-case scenario is one of the chief reasons for the subsequent Trust Fund buildup. Reality arrived somewhere in between their intermediate and worst-case scenarios, meaning that some of the margin for error was later manifested as mounting program surpluses. But as the Congressional Research Service (crs) later noted in an excellent 1997 paper, “Neither of the reports from the [congressional] committees made any reference to such ‘advance funding,’” and “there was very little understanding that a period of surpluses would be followed by a period of deficits.”

If this evidence seems overwhelming, none of it actually clinches the issue. But this does: The crafters of the 1983 reforms did not use an actuarial method consistent with solvency as defined using Trust Fund accounting. Today, the Trustees employ an actuarial method that, in effect, implicitly assumes that the Trust Fund is “real.” This is not, however, the method the Greenspan Commission used.

The Greenspan Commission’s methodology, by measuring future deficits only as a percentage of future wages, implicitly assumed that Social Security benefits would be paid by taxing worker wages at that time — not by drawing down the accumulated reserves of a Trust Fund. If the Commission had compared its calculation of actuarial balance with the result arising under Trust Fund accounting, this would have produced two different answers.

It is clear, based on this and much more documentary evidence, that the crafters of the 1983 reforms did not deliberately build up a large Trust Fund, nor would they have believed that so doing would pre-fund future benefits. They would not have agreed with the statements made by some today that Social Security faces no problems until 2037.

Because of the particular nature of the 1983 solution, it began to unravel almost immediately after enactment. With each passing year, a surplus faded into the past while a large new deficit appeared over the horizon, ensuring that insolvency would eventually again be faced. This facilitated a realization that the legislation had been imperfect.

The following years produced a number significant events affecting Social Security. One was little-noted but critical: a change in the 1988 trustees’ report that made the program shortfall appear roughly one-third smaller.

By 1988, it was more widely realized that Social Security was running significant annual surpluses and amassing a large Trust Fund — and further, that existing measures of actuarial balance were in mutual conflict. The trustees resolved this conflict by implicitly assuming the Trust Fund was being saved, discounting future shortfalls by the interest rate on its reserves and shrinking the apparent actuarial deficit. Because of this change, many today do not realize that we now face a much bigger long-range problem than we faced in 1983, compared apples-to-apples. The accounting change also carried other consequences for policy evaluations. Because the post-1988 method implicitly assumes that surplus revenues will be saved and earn interest, it biases policy consideration in the direction of near-term tax increases. Also, because it implicitly assumes that Trust Fund money is already being saved, the measure also biases against policy proposals to shift toward genuine pre-funding of future benefits.

Today, one often reads pronouncements about the size of the future Social Security shortfall or of the supposed fiscal effects of various policy proposals. One only rarely encounters recognition of how the 1988 accounting changes shape perceptions both of the current law’s shortfall and of proposals to address it. To sensibly chart our course going forward, we need to recognize the assumptions implicit in current accounting and to adjust for where they deviate from empirical reality. A general failure to do so has, unfortunately, undercut the policy debate through the present time.

At a 1989 conference on “Social Security’s Looming Surpluses,” as elsewhere, a bipartisan chorus of experts agreed that the mounting Trust Fund buildup in no way explained how future Social Security benefits would be paid. Economist James Buchanan noted that despite the Trust Fund, “there will be no increase in future income that will allow such [benefit] claims to be more easily financed,” while across the aisle Barry Bosworth agreed that actually saving the Trust Fund was “not a realistic option in the next few years.” This bipartisan analytical consensus led rapidly to bipartisan policy recommendations. The 1994–1996 Social Security Advisory Council (ssac), while sharply divided on many policy issues, unanimously recommended that partial advance funding of Social Security should commence. It further agreed that this would not occur within the existing Trust Fund structure. Moreover, to avoid a repeat of previous analytical shortcomings, the ssac recommended that future reforms aim for sustainable solvency, because the “long-term actuarial balance of Social Security should not be adversely affected solely by the passage of time.”

Following up, the 1999 Technical Panel of the Social Security Advisory Board similarly recommended that future reform efforts focus less on “actuarial balance” (with its implicit reliance on the Trust Fund) and more on avoiding large annual deficits. The Panel stated that it “would like to reinforce concerns about the overemphasis on 75-year actuarial balance,” and complimented the ssac for wisely choosing to define sustainability “in a way that would ensure that taxes and benefits were more or less in line after the 75th year.” Heeding this advice, the Social Security actuary began to routinely evaluate proposals not only for whether they achieved long-term actuarial balance on average, but whether they attained long-term annual balance irrespective of the Trust Fund.

When President George W. Bush pursued Social Security reform, not only Social Security policy but its underlying analytics entered a more contested realm. Some experts, contradicting their earlier analyses, argued anew that the Trust Fund did embody actual saving and that there was therefore no financing challenge for decades. This posture not only diminished the apparent urgency of action to repair Social Security finances, but it sowed unnecessary confusion as to what constituted an adequate solution. This flight from the analytical mainstream, which began in 2001 and continues through today, will make bipartisan compromise more difficult for however long it lasts. Meaningful bipartisan action on Social Security finances will only be possible if participants on both sides of the aisle restore a shared, accurate understanding of program finances, and avoid repeating the analytical mistakes that undercut the efficacy of the 1983 reforms.

Had the Greenspan Commissioners thoroughly analyzed the projected annual operations of the solvency plan eventually passed, they might well have modified their recommendations — either to maintain something closer to annual balance, or to ensure that earlier surpluses would be saved to enable the financing of later deficits. Because they did not, we are now unprepared to finance the large deficits soon arriving, and many have been confused into believing that problems are far more distant than they actually are.

We have seen how panels of experts over the years noted the shortcomings of the 1983 scorekeeping and offered recommendations to ensure they are not repeated in the next rescue attempt. Ironically, analytical confusion sowed by the 1983 reforms has made it more difficult for such a bipartisan rescue to recur.

The policy challenge

Stripped to its essence, Social Security policy comes down to a series of value judgments. We must together decide what kind of system we want, and then determine how to make that vision a reality. This requires a number of critical value judgments.

Perhaps the most fundamental such issue is whether we should close the shortfall by raising taxes or by slowing the growth of benefits. Under current law, these costs will rise dramatically in the upcoming decades, from less than 12 percent of worker wages in 2008 (just before the baby boomers began to retire) to more than 16.5 percent by the 2030s. Much of the reason for this is population aging; as the boomers leave the workforce, many more people will be collecting benefits. Another important reason is “wage indexation” — the feature of the retirement benefit formula that causes initial payments to new retirees to generally grow faster than inflation.

Due to wage indexation, scheduled benefits for future retirees are much higher than those paid today, and much higher than projected revenues can finance. Today in 2010, a typical medium-wage earner retiring at the normal retirement age (nra) has an annual benefit of $17,676. The medium-wage retiree of 2035 is scheduled to receive $24,023 annually (in today’s dollars) — a 35 percent increase — if also collected at nra. A fundamental question is whether we want a system in which the initial benefit level grows above inflation, when one important consequence is a swelling tax burden on workers and their employers.

For many policy analysts, constraining cost growth is the essence of the solution because cost growth is the essence of the problem. They rightly note that current law is biased in favor of a steadily more expensive system. Even if we fixed system finances entirely by constraining benefit growth, cost burdens facing our children would still rise markedly — to over 16 percent of wages by 2030 — not trending back down to today’s levels until many decades from now. Advocates of a cost-restraint solution also note, as I have, that we can relatively painlessly avoid imposing a tax increase on workers while also avoiding a decline in the real level of benefits — if we act today. And while we can fix Social Security without a tax increase, no one seems to know how to fix Medicare without one. This suggests that we should do what we can to avoid raising Social Security taxes.

There are arguments on the other side as well. Perhaps the central argument in favor of raising taxes is based on replacement rates. The replacement rate is, loosely speaking, the percentage of one’s pre-retirement earnings one receives as retirement income. If wages rise at one rate, while benefits rise at a slower rate, then Social Security benefits will only replace a declining percentage of pre-retirement wages. Some advocates believe that maintaining Social Security replacement rates (what wage indexing aims to achieve) is the appropriate policy goal. This is a legitimate viewpoint, but it is occasionally speciously argued. One misplaced argument is that Social Security benefits should rise with wages because contributions rise with wages. That sounds reasonable on the surface; the problem is that maintaining this correspondence isn’t mathematically possible in a pay-as-you-go system with our demographics. When the number of beneficiaries grows at a faster rate than the workforce, something must give: Either we must raise the tax rate to maintain wage-indexed benefits, or else we can only provide a rate of benefit growth that is less than wage-indexed.

One way or the other, younger generations will get a worse deal under current financing methods. Wage indexing doesn’t create benefit equity; it simply requires each succeeding generation to pay a higher tax burden to get the same replacement rate. The policy question we actually face is how much higher we should allow tax burdens to become, to pay benefits growing faster than inflation.

Once we decide what level of benefits to pay and what level of costs to impose, we must decide a second issue: Who will pay for these costs and when?

At one extreme of the possibilities is a fully pay-as-you-go system. Under pay-as-you-go, the government produces the revenue only as needed to pay benefits. This is essentially how Social Security works now. At the opposite side of the spectrum would be a funded system, such as one consisting solely of personal savings accounts. In a funded system, each generation builds saving — spending less than it earns — sufficient to fund its own eventual retirement benefits.

Since the 1983 reforms, debate has swirled about whether we should shift from pay-as-you-go to a fully- or partially-funded system. As noted, the 1994–96 ssac unanimously recommended partial advance funding. Its members disagreed on the best means (two groups favoring personal accounts, one group collective investment in stocks), but they agreed on the goal. They also agreed that it would not be accomplished through the existing Trust Fund mechanism. The central element of the case for pre-funding is intergenerational fairness. As we’ve seen, either tax burdens must rise or replacement rates must diminish under pay-go financing. This is why our current system is projected to impose net benefit losses upon younger generations. Alternatively, complete conversion to a fully funded system would place the largest costs on the generation(s) financing the transition, but result in the most favorable treatment of future generations.

If instead we choose partial pre-funding, we’ll relieve our children and grandchildren from some of the projected cost explosion, and we’ll need to generate enough near-term saving to fund a portion of our own future benefits. This middle ground of “partial advance funding” is where the majority of reform plan authors have landed.

A third fundamental question concerns the degree to which a person’s Social Security benefits should reflect her own contributions and how much they should reflect other people’s contributions. This choice is also understood by outlining the extremes of the available possibilities: In Model 1, a person’s Social Security benefit should reflect only what he or she contributed; in Model 2, a person’s Social Security benefit need have nothing to do with what he or she personally contributed. Social Security lies in a policy realm somewhere between Model 1 and Model 2. There is a link between individual contributions and benefits, but significant income redistribution as well. We must determine how much redistribution (if any) there should be in Social Security, and how it should be achieved.

Researchers have tended to find that the progressivity of Social Security’s benefit formula currently outweighs other regressive program elements. The Congressional Budget Office (cbo) declared in a 2006 report, “The Social Security system is progressive.” But this progressivity is far from consistent. So many factors affect one’s individual return that one’s own wage level is an unreliable determinant of how one will be treated by Social Security. When considering changes, therefore, we need to determine how much income redistribution we want, as well as how consistent and transparent it should be.

Most plans generally seek to retain or enhance the system’s progressivity. This bipartisan consensus exists for a predictable reason: Social Security faces a substantial shortfall under current law. To close it, someone’s taxes must be raised or the growth in their benefits slowed. Many are troubled by doing either to the poorest members of our society. Hence, these plans’ solvency-attaining measures affect only the middle-to-high-income range. This would render the system more progressive than current law. Beyond questions of average progressivity, there is a question as to whether we should render Social Security’s progressivity more consistent. This goal is at the root of proposals, like those of Andrew Biggs, to combine a first-tier benefit that eligible workers receive without regard to income, with a second-tier benefit involving no income redistribution. On average, this approach would be no more or less progressive than current Social Security, but it would increase the consistency with which this progressivity is delivered.

As for transparency: One needn’t follow the Social Security debate for very long to appreciate that the current system isn’t very transparent at all. Few people have any reliable sense of the proportion of their own contributions that result in benefits for themselves, versus the proportion redistributed to others. This opacity fuels a great deal of confused disputation over the equity of the current system and of proposed reforms. We could in theory improve the transparency of Social Security’s income redistribution by dividing the payroll tax into three roughly equal pieces revealing three broad trends. Part a would function like a personal account; each worker’s benefits would equal one’s contributions, times interest. Part b would represent the safety net; high-wage workers receive nothing from it, whereas low-wage workers receive above-market returns. Part c would designate that portion of workers’ taxes being transferred to previous generations, never to be received back as benefits.

Would this kind of transparency be good for Social Security? Some see in this type of system a danger that high-income taxpayers would withdraw their political support. Once high earners understand that they are receiving nothing from Part b or Part c they might seek to expand the earned benefit component (Part a) while shrinking the other parts. Desirable or undesirable, such accounting would provide a rough but fair depiction of how the system currently redistributes income. The question is whether we want this redistribution to become explicit and clearly delineated or to remain intermingled and obscured as it now is.

These are but three of the fundamental value judgments to be made when crafting Social Security reforms. A full understanding of many existing proposals, however, cannot be gleaned without appreciating a fourth: The plan authors’ emphasis on improving work incentives.

Many elements of current Social Security exert pressure on workers to exit the workforce. Among these are the nonworking spouse benefit, the benefit eligibility ages, the adjustments for early or delayed benefit claims, and the program’s method of tabulating one’s earnings history to offer poorer returns the longer one works. These factors combine to produce poor incremental returns for seniors and women especially, relative to what they would get by staying home. Some Social Security proposals include provisions to modify these features to improve the returns on work.

Most current Social Security plans can be understood in relation to these four spectra of value judgments here described. The authors of these plans understand that we don’t face a false choice between “defending” and “undermining” Social Security. Instead, we face fundamental value judgments on which well-intentioned experts offer a variety of compelling views.

The continuing debate

Thus far, i have described the evolution of the growing Social Security shortfall and the value judgments we face in addressing it. Now I will turn to the spirited debate over Social Security’s future. This debate is characterized by areas of stubborn factual confusion, fierce policy controversy, and underappreciated areas of common ground. Let’s turn to factual confusion first.

It continues to be argued by some that the projected Social Security shortfall is a product only of the overheated imaginations of the program’s trustees, based on overly conservative projections. This is an urban legend, built upon one false predicate after another. The myth typically consists of the following propositions:

- The trustees are arbitrarily projecting that future economic growth will be less than in the past.

- Were it not for these conservative growth assumptions, the shortfall or a good portion of it would disappear.

- In the past, the trustees’ projections have been too conservative and it’s likely that they are too conservative again.

Each of these contentions is false. Let us examine each more closely.

Economic growth. National aggregate economic growth is a product of two factors: growth in the number of workers and growth in output per worker (productivity). Over the past 40 years, productivity growth has averaged 1.7 percent annually. The trustees project that this will continue for the indefinite future.

The trustees are thus not anticipating that productivity rates will markedly change. What is changing is the rate of growth of the American workforce. This net growth is, of course, the amount of workers entering minus the amount of workers leaving. The generation now exiting the workforce is of unprecedented size; moreover, this generation did not have as many children as their own parents did. This results in slower labor force growth — which in turn means slower aggregate economic growth, if productivity growth resembles historical patterns. This concept shouldn’t be hard to understand. If one state’s population grows faster than another, for example, its economy typically grows faster, too. In 1997, New York’s economy was bigger than Texas’s. By 2007, Texas’s was larger. Was this because Texans had been more productive than New Yorkers over that decade? No — New York’s productivity had actually grown faster in the interim. Texas’s economy had grown more primarily because its population had grown faster.

There is no basis for the charge that the trustees are positing a slowdown in economic growth for no particular reason. This is why external bipartisan review panels have repeatedly signed off on the trustees’ assumptions as reasonable.

The relative importance of economic growth to the projections. The second component of the myth is that not only are the trustees’ economic growth assumptions unduly conservative, but most or all of the shortfall would disappear if they weren’t.

This is also untrue. The annual Trustees Report contains a probabilistic analysis showing how the fiscal outcomes vary under a wide range of economic and demographic assumptions. The qualitative picture doesn’t greatly change even at the far extremes of the possibilities. The projected insolvency date ranges only from 2032 to 2045, from the 10th through the 90th percentile of the scenarios. Nowhere in the 95 percent confidence band is there a single scenario in which Social Security doesn’t become insolvent. It is significantly more likely that program costs will ultimately absorb over 24 percent of worker wages than it is that the shortfall will disappear.

So, where does the notion come from that faster economic growth might by itself obliterate the problem? The notion comes from the irresponsible citation of a hypothetical projection contained within the Trustees Report called the “Low-Cost Projection.” This scenario is an illustrative compendium of individual variations in assumptions that could each conceivably shrink the shortfall. Any one variation might come to pass, but the chances of them all doing so are extremely slight. For all of these demographic and economic variables to break the same way is so improbable that even the trustees’ two-and-a-half percentile scenario is far more likely than this “Low-Cost Projection.”

The trustees’ projection history. The third element of the myth is that the Social Security trustees have a track record of being overly conservative in the past, so their current projections should be taken with a grain of salt.

This, too, is untrue. In reality, the trustees have a record of impressive (for federal government scorekeepers) projection accuracy and consistency. And, contrary to the myth, to the extent their projections have been imprecise, they have tended to be too optimistic about program finances. There will always be fierce policy disagreements over Social Security. But it should be better appreciated how policy conclusions can be predetermined by faulty, unexamined analytical assumptions. As an example, consider the following pictures of two alternative future courses for a hypothetical Social Security system:

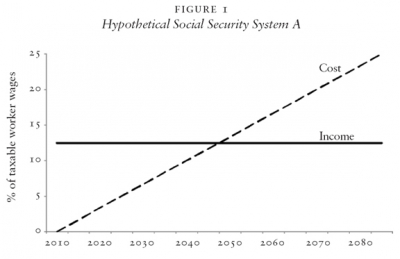

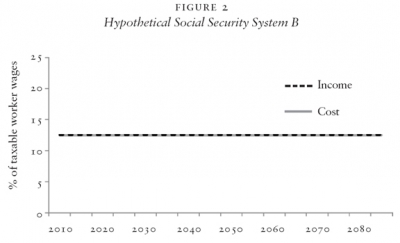

These two figures show projected income and outgo for two hypothetical systems. Each system has an incoming stream of revenue always equal to 12.5 percent of worker wages. These two imaginary systems differ in their payment obligations. System a (Figure 1) owes no payments at all until after 2010, but over time its costs rise without limit. It faces enormous annual deficits 50 to 75 years out, which grow still worse beyond then. System b (Figure 2), by contrast, is in perfect balance every year, as far as the eye can see (that’s why it appears that there is only one line in Figure 2 — income and costs are identical).

It should be obvious that System b is by far the more responsible course. It faces no foreseeable shortfalls and it’s possible that it never will. System a, by contrast, is clearly unsustainable. Not only is it unsustainable beyond 75 years, it faces massive problems even within the 75-year window. Within that time span it will eventually produce only half of the annual income needed to meet annual obligations. The point of this illustration is that if policymakers had inherited the dysfunctional System a, and had proposed responsible reforms to convert it to System b, then someone would be able to write a paper, based faithfully on the projections of the Social Security actuary, saying all of the following things:

- Converting to System b requires a multi-trillion-dollar transition cost.

- Even after 75 years, this transition cost wouldn’t be fully paid off.

- Converting to System bworsens the system’s actuarial balance.

This may seem ridiculous, but this is exactly the methodology that has often been used to critique Social Security reform proposals in recent years. The reason that System b shows a multi-trillion-dollar “transition cost” is that System a projects large near-term surpluses, stretching into the trillions. Switching to System b would eliminate them. The finding of the huge transition cost is based on the implicit assumption that System a’s surpluses would be saved. Not only that, but one would also find that the transition cost would not be fully paid off even after 75 years. This is because System a is presumed to have a positive effect on federal debt over that time because the saving of surpluses will earn interest (or, equivalently, reduce other interest payments). Similar reasoning concludes that converting to System b worsens the program’s actuarial balance.

Clearly, we need a reality check: In the real world, it’s ridiculous to claim that System b is inferior to System a. System b is in perfect balance in every year. System a’s viability, on the other hand, depends on several dubious assumptions about government behavior. Any methodology that finds System a to be superior to System b is highly flawed; if it is not thrown out entirely, it should at least be used sparingly with full disclosure of its shortcomings. But this flawed methodology is exactly the type that has often been misused to allege terrible fiscal effects of Social Security reform, especially proposals containing personal accounts.

If our national policy debate is to produce a reasonable outcome, any methodology that finds System a preferable to System b ought not to be the sole basis for policy conclusions. If readers have embraced conclusions about Social Security finances based implicitly on such methods, they would do well to wipe clean their slates of perception and to approach the problem anew.

Once we get past these points of analytical confusion, it turns out that serious Social Security proposals from left to right exhibit a remarkable degree of substantive overlap. If policymakers from both sides of the aisle found it in their respective interests to reach a Social Security accord, they would discover that many of its features are already apparent. The first area of common ground relates to the scorekeeping issues just described. Since 1983, there has emerged a bipartisan expert consensus that the previous method of computing “actuarial balance” was inadequate to thoroughly assess proposed legislation. Recommended instead is the standard of balanced and sustainable annual cash flows by the end of the valuation period.

In plain English, this means that however far out in time we choose to look, by that point incoming program tax revenue should be at least as high as outgoing benefit obligations — and be on a trend to stay that way. For over a decade, the Social Security actuary has routinely evaluated reform plans by this standard. Obviously, it’s not enough that Social Security be in balance only in the last year of the valuation period; it needs to be balanced in the aggregate on the long road to that last year. The standard of sustainable annual cash flows must be in addition to the traditional solvency standard, not in lieu of it.

A second widely shared value is revealed in the fact that recent Social Security proposals generally make no changes to benefits for current beneficiaries. This is a principle premised upon fairness: It is only acceptable to change benefits if those affected have a reasonable chance to plan for and adjust to those changes. For today’s seniors, it’s too late to do that; they’ve retired with a set of benefit expectations, and they can’t go back and live their working lives over again. This principle is honored in proposals across the political spectrum.

Existing proposals also reflect a striking consensus on a third issue: the treatment of low- income workers. The essence of this consensus is to minimize any impact on the benefits of low- income workers if they retire at the nra or later. Some proposals make no changes whatsoever to benefits for the lowest-income workers. Others would only affect lower-income workers (roughly the bottom quarter of the wage distribution) to the extent that all benefits are adjusted for life expectancy. Of course, this leaves the upper 75 percent of the wage distribution to be affected by a legislated solution — a large fraction of the whole. This includes many workers of below-average income. Had we acted earlier, we could have confined changes to a smaller fraction of the income spectrum. There is a cruel irony in this outcome, for those who have counseled delay sometimes justify their stance by citing the value of Social Security to the most vulnerable in our society. But the math cannot be escaped; the longer we wait, the deeper any solution must dig into the pockets of the less wealthy.

A review of existing Social Security proposals shows a fourth area of common ground with respect to tax revenues. Fiscally sustainable plans generally take one of four approaches:

- Don’t collect new revenues at all (Republican plans).

- Collect new revenues only to offset payroll tax revenue redirected to personal accounts (Republican and bipartisan plans).

- Collect new revenues only to finance “add-on” personal accounts (bipartisan plans).

- Phase in new revenues gradually as needed to meet increasing benefit payments (Democratic plans).

Those appear to be the only viable options. Notably, each reflects a determination to avoid the 1983 mistake of permitting the government to collect — and spend — surplus program tax revenues.

A fifth area where there is bipartisan consensus is — believe it or not — on individual retirement savings accounts. This may seem surprising. But every congressional author of a recent proposal to render Social Security financially sustainable supports personal accounts of one kind or another. Only one such proposal would not establish personal accounts, and even that proposal’s author expressed support for the concept. He introduced his proposal without them in the hopes of attracting bipartisan support (it did not).

It is obvious that whether such an account is inside or outside of Social Security, whether it involves an employer mandate, and whether it requires additional contributions from workers are all issues on which there are sharp disagreements. But if there is to be a bipartisan accord, there likely needs to be a decision on how to implement the broadly shared vision of a universal retirement savings account. If these decisions are made wholly apart from a Social Security negotiation, it could well kill the last remaining prospects for a bipartisan deal. The personal account is the element that could make additional revenues acceptable to Republicans, while making a solution without traditional tax increases acceptable to Democrats. Taken together, these five elements of reform could define the substantive contours of a potential bipartisan solution. But to realize this goal of a sustainable, effective Social Security system, we all need to conduct ourselves much better than we have been doing.

That statement warrants qualification: We needn’t necessarily do better if we don’t care about Social Security’s financial stability, intergenerational fairness, or efficacy in serving societal goals. In that case, we can keep on doing just as we are doing — i.e., allowing these aspects of the program to inevitably deteriorate while we impugn one another’s motives and demonize the actions required to place Social Security on a stable and effective track.

We must, however, do better if we believe that Social Security’s financial stability is important and that the program should serve future generations at least somewhat as it has served us. Even if we care about nothing beyond these principles, we need a loftier Social Security discussion than we have had. We need to listen to policy opponents and to treat their concerns as signifying something other than malicious intent. But doing better means more than listening to one another. It also means being more candid about the downsides of proposals that we ourselves favor.

We must do better, and I believe we will. The question is when. For workers in Social Security, the process cannot move quickly enough. Each year that we dither, the cost facing younger generations grows larger. We must do better — and soon.