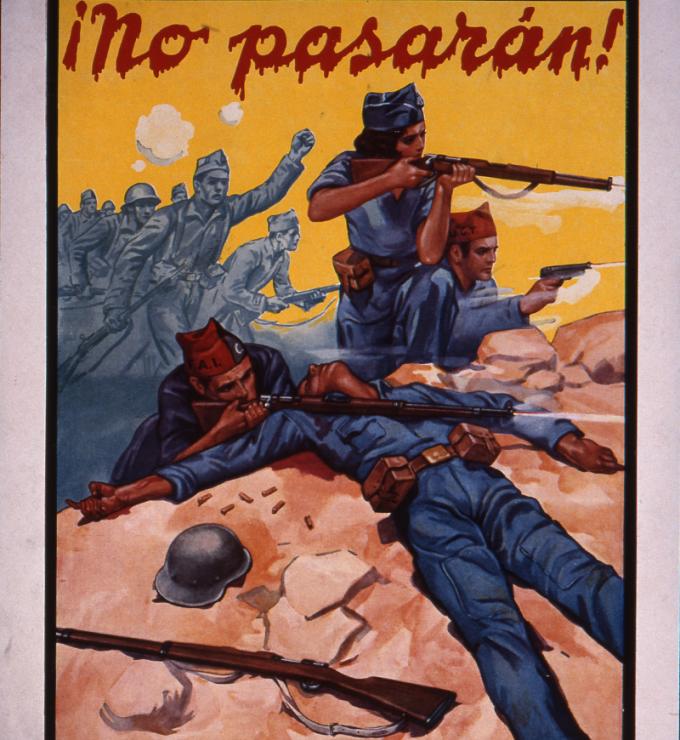

This essay analyzes the recruitment and operational use of veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II. It focuses on the deliberate strategy of OSS director William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan to harness the experience of former International Brigade volunteers, despite their political stigma. Through close examination of individual cases—including Milton Wolff, commander of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion—the article argues that Spanish Civil War veterans played a formative role in early American unconventional warfare and resistance liaison operations.

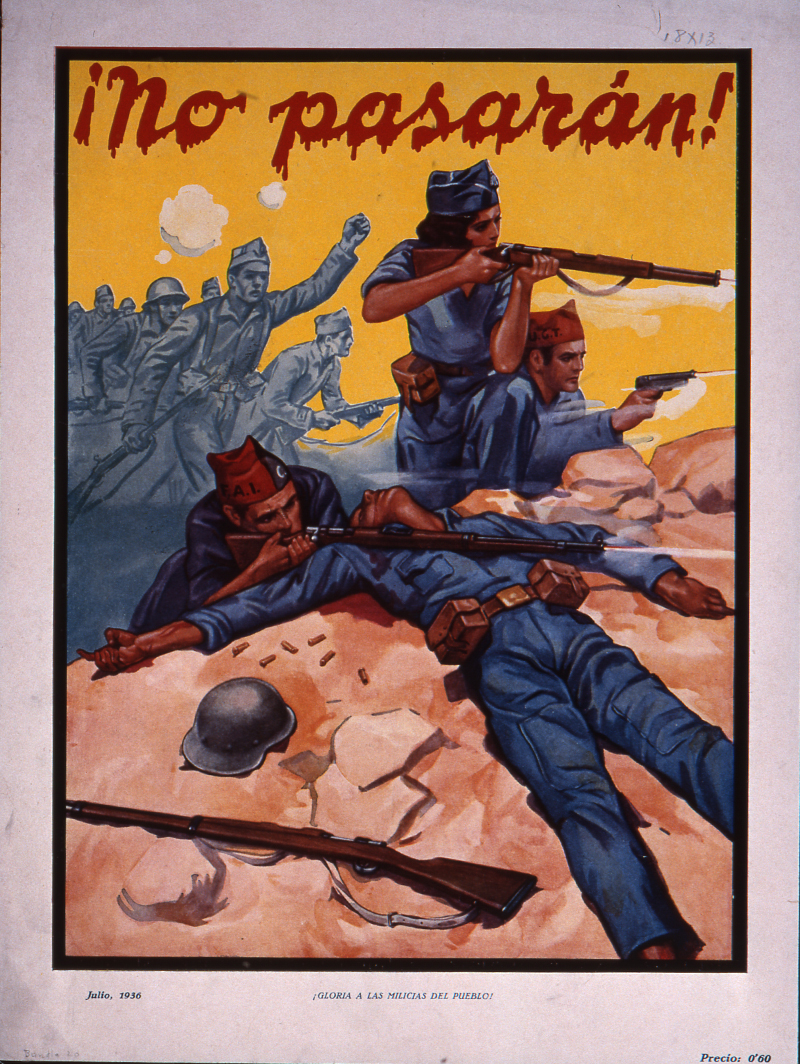

In March 1938, Milton Wolff assumed command of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion on the Ebro front in Spain. He was twenty-four years old, leading exhausted American volunteers against one of the most modern armies in Europe. Four years later, as the United States fought a global war against fascism, Wolff and several of his former comrades found themselves on an altogether different battlefield: the clandestine world of the Office of Strategic Services.

The transition from Spain’s battlefields to the OSS’s covert operations was neither automatic nor politically uncomplicated. Veterans of the Lincoln Brigade were admired for their early stand against fascism yet distrusted for their association with communist networks. Nevertheless, under the leadership of William J. Donovan, the OSS became one of the few American institutions willing to exploit their experience. This article examines that decision, focusing on how former Lincoln Brigade fighters were recruited, deployed, and utilized in World War II.

William J. Donovan’s conception of intelligence and special operations differed sharply from that of traditional military planners. When the OSS was established in 1942, the United States possessed little institutional knowledge of guerrilla warfare, sabotage, or resistance coordination. Donovan therefore prioritized practical experience over ideological vetting.

The Spanish Civil War offered a rare training ground. Lincoln Brigade veterans had fought in multinational units, endured supply shortages, coordinated with civilian populations, and faced mechanized enemy forces under conditions of asymmetrical warfare. Donovan understood that such experience could not be replicated quickly through training. As a result, the OSS selectively recruited former brigadistas, often shielding them from scrutiny by other agencies.

Milton Wolff represents the most prominent and symbolically significant example of this transition. As the final commander of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, Wolff had overseen American volunteers during the most intense phase of the Spanish Civil War. His leadership combined battlefield competence with political commitment, earning him respect among international volunteers.

After the U.S. entered World War II, Wolff enlisted in the Army and was subsequently recruited into intelligence work linked to OSS activities. While he was not a field operative in the romanticized sense of OSS legend, Wolff’s role was no less important. He worked in intelligence analysis and liaison capacities, drawing on his firsthand knowledge of European anti-fascist networks and resistance movements.

Wolff’s wartime service illustrates a broader pattern: the OSS often deployed Lincoln veterans where political sensitivity, cultural knowledge, and credibility with resistance groups mattered more than conventional rank. His postwar marginalization during the Red Scare further underscores the conditional nature of his wartime acceptance.

Beyond Wolff, several Lincoln Brigade veterans moved directly into operational OSS roles. Irving Goff, who had fought in Spain, served in North Africa and later in Italy, where he acted as a liaison with Italian partisan forces. Goff’s familiarity with left-wing resistance movements allowed him to operate effectively in politically complex environments that frustrated conventional Allied officers.

Vince Lossowski, another Spanish Civil War veteran, conducted OSS missions behind enemy lines in North Africa and Italy. His work included training guerrilla fighters, coordinating sabotage, and organizing resistance units. Lossowski’s career demonstrates how Spanish Civil War experience translated directly into OSS operational doctrine.

William Aalto, recruited through personal recommendations from fellow Lincoln veterans, underwent OSS training in demolition and guerrilla tactics. Though his operational career was curtailed by injury, Aalto’s papers reveal the informal recruitment networks linking OSS personnel to their Spanish Civil War past.

The OSS deployed Lincoln Brigade veterans primarily in roles involving resistance coordination, training, and liaison work. These assignments reflected both their strengths and the limits of institutional trust. While their ideological commitments raised concerns, those same commitments often enhanced their credibility with European resistance movements dominated by left-wing organizations.

Donovan’s willingness to accept this contradiction was instrumental to OSS effectiveness. However, the political calculus shifted rapidly after 1945. Many of these veterans—Wolff included—were later investigated, surveilled, or excluded from postwar intelligence institutions.

The integration of Abraham Lincoln Brigade veterans into the OSS was not accidental, nor merely anecdotal. It was a calculated response to the strategic demands of unconventional warfare. Their careers illuminate both the origins of American special operations and the fragile alliance between ideological outsiders and state power. Valued in wartime, distrusted in peace, Lincoln Brigade veterans occupy a liminal space in U.S. military and intelligence history—one that deserves closer scholarly attention.