- Finance & Banking

- Economics

- Economic

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

The Genius Act, passed in July, sets out a framework for regulations for US payment stablecoins—a digital currency to be provided by the private sector. The rationale for this legislation is to promote stablecoins as a form of digital money that will take on the advantages of new digital technologies such as the blockchain. An alternative form of digital money is central bank digital currency, which is being developed across the world but not in the United States.

The Genius Act opens up a number of issues on the implementation of a safe private-sector-issued currency that were dealt with successfully more than a century ago and which may need to be revisited before we achieve a satisfactory outcome. In this paper I analyze how a safe, successful private-sector currency was implemented in the United States and Canada long before the establishment of central banks. The lessons from three earlier eras of private currency have resonance for the Genius Act. My focus will be primarily on stablecoins as a possible form of domestic currency and less on its wholesale and international possibilities.

Digital currencies must satisfy the basic functions of money as a unit of account, a store of value, and a medium of exchange. Digital currencies are a financial innovation much as banknotes were over specie coins, as pointed out in 1776 by Adam Smith:

The gold and silver which circulates in any country may very properly be compared to a highway, which, while it circulates and carries to market all the grass and corn of the country, produces itself not a single pile of either. The judicious operations of banking, by providing, if I may be allowed so violent a measure, a sort of wagon-way through the air, enable a country to convert as it were, a great part of its highways into good pastures and cornfields, and thereby to increase very considerably the annual produce of its land and labor. . . .

[The Wealth of Nations]

What are the advantages?

Proponents argue that stablecoins would provide instant and costless access to the payment system, which would be a significant saving, especially for merchants whose cost at present to access the payments system is considerable; and would be a unit of account because stablecoins, unlike cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, are defined in terms of dollars and safely backed by dollar assets. They would also serve as a store of value, especially if they were interest-bearing. Other advantages claimed for stablecoins include greatly reducing the costs of international transactions, and financing the crypto space (also of course, funding the black sector).

The key feature of the Genius Act is that it allows banks like JP Morgan, qualifying state chartered entities, nonbank financial institutions, crypto companies like Tether and Circle, and US branches of foreign banks to issue digital stablecoins defined as currencies backed 100 percent by US short-term Treasury securities, cash, uninsured bank deposits, reserves at the Federal Reserve, or money market funds (MMFs) and repos (repurchase agreements) based on government securities.

The act distinguishes between two types of issuers: large issuers with more than $10 billion in notes and small issuers with less than $10 billion. The large issuers would be regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve, and the FDIC, and the smaller issuers by state authorities.

Key features of the Genius Act include:

- Stablecoins would be fully redeemable on demand.

- They would not be legal tender.

- They would not bear interest.

- The issuers would not be bailed out by US monetary authorities should they become insolvent.

Free Banking falls short

The framework for payment stablecoins has great resonance to other such arrangements in the monetary history of the United States and foreign countries. The issue in the past was to create a safe, uniform currency for which the “no questions asked” principle (NQA) would be upheld—that is, the face value of the currency would always be equal to what it would be accepted for in exchange. Earlier legislation in US history to create NQA private currency either was unsuccessful—in the Free Banking era of 1837–63—or took a lengthy process of learning by doing to become successful, as in the National Banking era of 1864–1914. The Genius Act has elements of both. Canada’s experience with private banknotes also went through a similar learning process.

Financial innovation in Europe in the eighteenth century led to the use of paper banknotes as a low-cost substitute for specie. The First and Second Banks of the United States from 1791 to 1836 issued banknotes convertible on demand into specie, which, along with specie coin, were moving the country in the direction of a safe, uniform currency. States also chartered note-issuing banks whose paper often circulated at a discount but which, by forced redemptions of the two central banks, also moved towards NQA currency status.

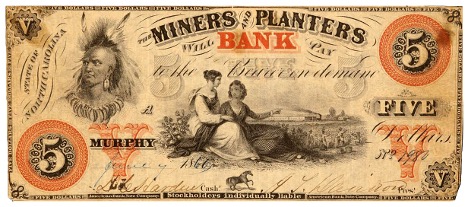

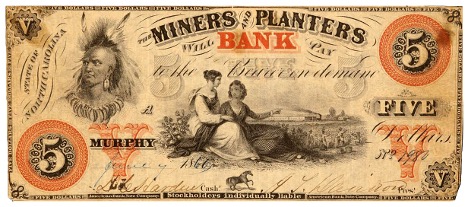

In the Free Banking era, the states regulated note-issuing banks. Free banking had several important features: it took minimal capital and red tape to set up a bank, in contrast to the earlier chartering process; free banks could issue notes backed by the security of state bonds (some states stipulated the bonds valued as at par and some at market value); the notes were to be immediately redeemable on demand in specie; and the banks were regulated and supervised by state authorities.

The Free Banking era did not satisfy the NQA principle. Bank notes circulated at various discounts reflecting the quality of the bond backing, the soundness of the bank, the quality of the state regulations and supervision, and the distance of the note from the issuing bank. Valuing the myriad different banknotes was not costless, despite the wide use of counterfeit detectors—magazines that listed fraudulent and broken notes as well as discount rates on others.

In the Free Banking era, counterfeiting was widespread, many banks failed, and the subsequent financial instability was manifest in two severe bank panics that involved runs from banknotes into specie. Not all states were problematic, however. The variance of performance ranged from good—such as in New York and Massachusetts, with sound regulations and supervision—to bad, such as in Michigan and other frontier Midwest states. with less-than-stellar governance and instances of wildcat banking.

In sum, this experience represents a cautionary tale for the small-issue stablecoins to be regulated and supervised by the states under the Genius Act.

The National Banking era, 1864–1914

The National Bank Act of 1864 was passed during the Civil War when the Confederate states (opposed to federal power) were absent. It was designed to create an NQA currency and overcome the flaws of the Free Banking era—that is, to create a national uniform safe currency to be perfectly convertible into government-issued (lawful) currency (greenbacks and specie). It also was designed to raise revenue for war finance.

Under the NB Act, agents could provide capital to establish a national bank anywhere in the United States. The highly capitalized unit banks could issue national bank notes up to 90 percent of the value of US government bonds deposited with the Treasury. Issuing these non-interest-bearing notes was a profitable source of seigniorage revenue. These notes were to be perfectly redeemable into specie or other lawful money on demand. The shareholders of the national banks were subject to double liability. National banks were required to hold reserves in specie and lawful money; the reserve requirement depended on their location in large or small centers. The national banks were to be regulated and supervised by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), a branch of the US Treasury.

As described by Warren E. Weber, it took a number of years to establish a safe and uniform currency that satisfied the NQA principle. Many innovations were required, almost all involving government regulation. Among the ways notable problems were overcome:

- Making national bank notes issued by myriad individual banks acceptable at par at every national bank in the country. This required the Treasury to set up note redemption centers in every major city.

- Treasury provision of insurance against losses to note holders when national banks failed (5 percent failed over the whole period).

- The Treasury setting up a gross clearing mechanism, the National Bank Note Redemption Agency, in 1874. To fund it, each national bank was required to deposit in lawful money 5 percent of its note circulation with the Treasury.

With these innovations, national banknotes became perfect substitutes for other forms of currency, and the United States had an NQA monetary system.

The lesson for the Genius Act regime is that it took government establishment of enforceable rules for good behavior to prevent free riding and the incentive to cut corners, thus solving the acceptance at par, redeemability, and insurance problems that plagued that era. There is little in the Genius Act detailing exactly how similar problems would be solved. In the case of the national banks, it was the Treasury that solved these problems. It will be interesting to see what happens when significant defaults occur because of such issues, possibly spilling over into the real economy.

Moreover, a safe currency in the National Banking era did not mean overall monetary and financial stability. The National Banking system, in addition to providing safe banknotes, also engaged increasingly in deposit banking, as interest-bearing deposits were more profitable and the expansion of the national banknote issue was limited, in part, because of the convenience yield of Treasuries. A key flaw of that system was that the deposit-based fractional reserve banking system was prone to banking panics when depositors, fearful for the safety of their deposits, attempted en masse to convert them into currency (regardless of whether they were national banknotes or lawful money of any type).

Also, the United States in this period was on the gold standard, and financial shocks from abroad could severely affect the banking and financial system and hence the real economy.

Other well-known flaws of the national banking system were: the inverted pyramid of credit (most of the nation’s bank reserves were concentrated in New York City and invested in the call loan market, thereby linking stock market crashes to banking panics); and the absence of a mechanism to stabilize seasonal shocks. The Federal Reserve System was established to overcome these problems, although it took seventy more years for it to learn how to be a successful central bank

Canada’s chartered banks

Canada had a private chartered banking system without a central bank until 1935 which, like the national banks in the United States, provided a uniform safe NQA currency. The bank shareholders were also subject to double liability. As in the United States, the chartered banks could issue banknotes backed by specie, bonds, and capital. The banks were initially regulated by the provinces and then, after Confederation in 1867, by the federal government.

The Canadian nationwide branch banking system had no banking panics in its entire history and fewer bank failures than in the United States. However, as in the United States, it took a long time to acquire a NQA. The requisites for creating an NQA involved both the banks working through the Canadian Bankers Association (their cartel) and the federal government via a series of decennial bank acts to create a note insurance scheme, a clearing mechanism very similar to the 1874 US version, and a mechanism to prevent bank failures from having systemic consequences. Designated banks would take over troubled banks before they became insolvent. Unlike the United States, Canada maintained monetary and financial stability, lessening the case for a central bank.

The lesson from the Canadian experience, as from the National Banking era in the United States, is for government regulators along with the stablecoin issuers to work out the pressing problems of convertibility, redemption, and insurance in a framework with enforceable rules to avoid systemic spillovers.

How to make it work

Several policy lessons arise from the historical comparisons to US stablecoins under the Genius Act.

First, it is possible to have a safe, uniform NQA stablecoin system with enforceable rules for good behavior. But problems leading to systemic risks will inevitably require Federal Reserve (and other monetary and regulatory) intervention. These include shocks to the backing of stablecoins coming from global and self-induced US policy mistakes on the value of the bond backing. This happened in the National Banking era.

Second, in all three eras examined here, banks failed because of fraud and malfeasance as well as shocks to the real economy. This led to contagion and considerable financial stress including systemic panics.

Third, shocks coming from other parts of the global financial system could spill over into the stablecoin space, and vice versa. The Genius Act as it stands has no provision for dealing with them.

A further lesson from the history of private currencies in virtually every country is that private banking/currency systems failed at some point to maintain the NQA principle and even broke down in the face of systemic shocks. This led to the creation of central banks. It would not surprise me that yet-to-be-revealed flaws in the Genius Act, combined with totally unknown shocks, could lead to even the United States introducing a central bank digital currency.