- International Affairs

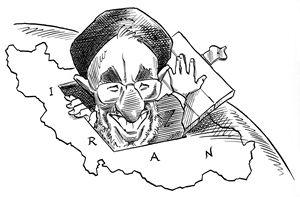

The struggle of Iran’s reformists to shine the light of

democracy and pluralism on the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) has given rise to a widespread expectation among scholars and policymakers that the country is headed toward a cataclysmic collision. With a parliament controlled by a bloc of popularly elected reformists and an executive dominated by a "Supreme Leader" chosen by a clerical council known as the "Council of Experts," Iran seems embroiled in a contemporary version of the age-old standoff between "kings and people." One way or the other, it is argued, the pivotal question of sovereignty must eventually be resolved.

These expectations of either a major "breakthrough" to democracy or, alternatively, a retreat to full-fledged autocracy, have been fed by the recent flurry of activity by none other than Reza Pahlavi, the son of the late shah. A keen advocate of representative democracy who, after many false starts, has finally shed the metaphorical feathers of his father’s defunct Peacock Throne, Reza’s call for genuine reform in Iran resonates among segments of a youthful population disillusioned with President Mohammad Khatami’s cautious incrementalism. Thus after a Los Angeles–based, pro-monarchy satellite TV station beamed its message of liberation to Iran in early October 2001, thousands of young spectators at an international soccer game in Tehran not only denounced the regime but also, to its horror, praised Reza Pahlavi. Although inspired by the satellite broadcasts, these protests were in fact largely spontaneous outbursts that reflected the growing desperation of Iran’s youth. Indeed, they soon spread to other cities, so that by the end of October, soccer matches had become the major venue of social protest. Encouraged by these unprecedented outbursts, and sensing an opportunity supposedly afforded by the Bush administration’s war on terrorism, some American scholars of Iran declared on CNN that, with a little push from the United States, the clerical regime might very well collapse.

Such expectations are unduly optimistic if not naive. The IRI has sunk institutional and ideological roots that are far deeper and more durable than anything ever realized by the late shah. Whether we like it or not, the principle and practice of clerical rule have proven capable of enduring considerable external and internal strain. The probability of collapse or rollback is slim indeed.

The assumption that the IRI will either fall under popular pressure for change or bury its reformist enemies in a heap of unadulterated clerical repression feeds a continuous watch for signs that the current political struggle has reached a critical mass that will send Iran hurtling in one direction or the other. But there is another possibility: that the regime will occupy a very different kind of position, not along a linear continuum from autocracy to democracy, but rather in a multidimensional, dissonant political purgatory that is contradictory, confounding, and—most of all—quite sustainable.

Negotiating Existential Claims

When autocracies fail to implode, there is always the possibility that opposition moderates will hook up with regime soft-liners and negotiate a political understanding or pact that allows for a measure of political openness—but without necessarily threatening the most vital political and social interests of the ruling elite.

Is such a pact possible in Iran? The notion presumes the existence of a clear contingent of regime soft-liners on the one side and a clear bloc of opposition moderates on the other. The challenge for both sides is not only to forge an alliance but to do so in ways that do not threaten the hard-liners within their respective camps. In empirical terms, the task before President Khatami and his allies in parliament—who have controlled some two-thirds of the seats since their victory in the 2000 elections—is to find within the conservative clerical establishment moderate allies who have the organizational and ideological strength to overcome the hard-liners’ opposition to any hint of reform.

Two obstacles have thus far blocked an alliance. First, although it sounds paradoxical, the ideology of the reformists itself constitutes a barrier. In contrast to Eastern Europe or Latin America, the negotiation of political pacts in Iran has not been about dividing the economic pie. Rather, it has been about an existential issue, namely, the very identity and nature of the Islamic Republic. Despite the many differences within the heterogeneous alliance that constitutes the reformist movement, all advocates of change agree that the growing apathy of the young can only be cured by distancing the mosque from the state. Absent real religious freedom in society, the reformists assert, there can only be a Potemkin Islamic state whose facade is incapable of hiding the reality of mass disillusionment. By contrast, the conservatives hold that any effort to get the state out of the business of imposing faith constitutes a slippery slope to secularism and thus the destruction of the ideological and institutional pillars of Iran’s Islamic state. For the conservatives, the sacred mission of the state is to create and sustain an Islamic society. By definition, this dispute cannot be easily negotiated. How does one tinker with an institutional arrangement that, according to the Iranian constitution, allows for a measure of public opinion so long as it is ultimately defined by the Supreme Leader and his allies in the Council of Guardians (a body that is constitutionally empowered to veto all legislation it deems contrary to Islamic law)?

Second, there is an absence of an institutionally and ideologically coherent bloc of moderate conservatives, by which I mean clerics who believe that a measure of greater religious (and thus political) freedom will not be the beginning of the end. Prominent conservative intellectuals have tried to make this case, the most well known of whom is Dr. Taha Hashemi, a centrist cleric whose Entekhab newspaper provides a widely read forum for both conservatives and reformists. But Hashemi’s efforts have collided with the reality that reformists and conservatives espouse opposing visions of authority. Perhaps more important, from the subjective vantage point of hard-line clerics, they have never seen convincing evidence that the circle can be squared. To put it bluntly, President Khatami and his allies have never clearly explained how his popular (and populist) slogan of "Iran for all Iranians" can be instituted without opening the doors to those reformists who ultimately espouse nothing less than an Islamic Reformation.

Apart from such ideological barriers, Hashemi has faced the daunting challenge of creating an institution through which like-minded conservative clerics can mobilize a wider following among young Iranians. By contrast, hard-liners have an array of constitutionally mandated organizations that not only control the Council of Guardians, the Council of Experts, and the entire judiciary but also mobilize through—and indeed are an integral part of—informal networks of clerics and disciples that are deeply rooted in the most conservative seminaries of Qom, the clerical capital of Iran. Moderate conservatives have recently created several new associations, but these embryonic entities cannot hope to compete with the institutional assets that the hard-liners command.

Confrontation versus Accommodation

Given the imposing obstacles that have worked against a regime-opposition pact, it should come as no surprise that Iranian politics has been marked by a fierce power struggle since Khatami’s first election in May 1997. Within two years, the conservative judiciary shut down nearly all opposition newspapers and sentenced several leading reformist intellectuals for "insulting" the legacy of Ayatollah Khomeini or impugning the "Islamic" foundations of the state. It is worth noting that two of these were prominent clerics, one of whom—Abdollah Nuri—was once a key ally of Khomeini’s. Paradoxically, the victory of the reformists during the 2000 elections in some ways made things worse. In contrast to the previous parliament, which was largely made up of conservatives (or at least deputies who did not share the implicit reformist ideology of Khatami’s most vociferous supporters), the new parliament was controlled by the reformists. Fearing an efficacious alliance between Khatami and the new majority of reformists in the parliament, the judiciary not only redoubled its efforts to shut down the opposition press but, in an unprecedented move, initiated charges of slander against several deputies. Khatami’s reelection in June 2001 did little to thwart this crackdown; indeed, it may have only convinced hard-liners that they should pursue their opponents to the bitter end.

Yet if the rise of the reform movement has provoked a predictable backlash from hard-liners, it has not yet produced the bitter end. On the contrary, what is most notable about the Iranian political scene is the persistence of a power struggle despite the many obstacles to a regime-opposition pact and despite the determined efforts of Khatami’s conservative enemies. Reformist deputies have initiated several bills to protect individual freedoms (all of which have been vetoed by the Council of Guardians) and, in the wake of September 11, took the risky decision to form a special parliamentary committee whose task was to explore possibilities for an American-Iranian rapprochement.

Of course, the conservatives may simply be biding their time. Rather than give reformists no choice but to exit the system, the conservatives are wearing them down in the hope that disillusionment will produce apathy and withdrawal rather than anger and political engagement. Recent rumors that the judiciary is about to launch charges of financial corruption against reformist deputies may be part of such a strategy. "Troublemakers" would then be replaced with acceptable deputies in by-elections from which any candidate deemed unqualified by the Council of Guardians would be excluded. Indeed, the November 2001 by-elections seem to presage this tactic. During these elections—held to fill seven seats left vacant by the death of reformist deputies in an air crash—the Council of Guardians disqualified scores of reformist candidates.

Yet the persistent power struggle in Iran is a function of much more than this kind of eminently rational repression strategy. In a much more fundamental sense, and despite the equally rational obstacles to a pact, the possibility for an accommodation—at least on an informal level—not only endures but is fostered by the institutional logic of the Islamic Republic. From the beginning, Ayatollah Khomeini and his allies, rather than impose one clear-cut Islamic vision of political community, allowed an arrangement that blended notions (and institutions) of clerical rule with the principle (and institutions) of republicanism. Of course, the 1979 constitution subordinated the latter to the former. But the notion that elections mattered and that what parliament said had to be taken into account, even by the Supreme Leader, never died. Indeed, it was championed by the Islamic Left, a group of lay intellectuals and clerics that constantly upheld the authority of parliament as the chief representative of the Iranian masses. Moreover, even Khomeini defended the principle that parliament was the highest authority, an assertion that blatantly contradicted the constitution and the power that it accorded the Supreme Leader.

Khomeini’s support for the Islamic Left was equivocal. Indeed, the key to the relative stability of Iran’s political system during the eighties was the central role that Khomeini—as Supreme Ruler—played as a charismatic arbiter of two competing factions, the Islamic Left and the clerical Right, which championed the absolute authority of the faqih, or "Ruling Jurist" (Khomeini). In the wake of his death and replacement by Ali Khamanei, sustaining this balancing act became much more difficult for two reasons.

First, Khamanei is in no sense a charismatic leader. Lacking Khomeini’s capacity to command support among a wide spectrum of the population (and thus his capacity to obscure the fault lines within the regime), Khamanei chose in effect to ally himself with the clerical Right and thus became its captive. The Supreme Leader is in fact not supreme: The Council of Experts has periodically sent Khamanei oblique signals that he should not move too close to Khatami and his reformist allies. As a result, Khamanei has often lacked the freedom of maneuver he needs to prevent a deadly polarization of the political arena.

Second, the divisions between the Islamic Left and clerical Right are far more divisive than in the past. In the 1980s, these divisions were largely about economics: The Islamic Left championed a kind of state socialism; the clerical Right—although often benefiting from state control of the economy—advocated the principle of private property. However, in the wake of the persecution of the Islamic Left during the early 1990s, many prominent Islamic leftists became disillusioned with the quasi-Islamic populist vision of democracy they had earlier advocated, one that called for subordinating the rights of the individual to those of the community. Thinkers/politicians such as Khatami began to push not only for liberal democracy but for the idea of distancing mosque and state. Confronted by this ideological shift, Khamanei has understandably found arbitrating the essentially political differences between Left and Right far more difficult.

That said, there is reason to believe that a return to something resembling the old balancing game is still possible, even in the contentious arena of current Iranian politics. To begin with, over the last two years reformist leaders who advocate a go-slow, nonconfrontational approach have prevailed over the most radical elements within their movement. Although they have not forged an alliance with moderate conservatives, these moderate reformists have convinced the leaders of the Islamic Participation Front (the key reformist grouping) that rather than challenge the very premise of clerical rule—as many reformists did during the first few years following Khatami’s election—reformists should now focus their energies on building institutional linkages to the wider society and addressing economic reform, education, and drug addiction. Khatami appears to support this accommodationist position.

The other reason an accommodation might become feasible is that Khamanei has taken some actions suggesting that he is trying to establish his autonomy from, and thus authority over, the most hard-line clerics. The most dramatic indication of this is his recent decision to pardon a parliamentary deputy who had been convicted by a hard-line clerical court of defaming Islam. Of course, it is too early to tell whether Khamanei’s pardon indicates a clear trend in favor of containing the repressive instincts of the judiciary. Nor does his pardon resolve the ongoing confrontation between that body and parliament. But, for the moment, it could signal the hard-liners that they should back away from their apparent plan to whittle down the number of reformists in parliament until they no longer have a majority. Khamanei most likely understands that it is simply not possible to have any kind of social and political peace in Iran if the authority of parliament is completely negated. To do so would only court an explosion.

Implications for U.S.-Iranian Relations

Such an explosion cannot be excluded. The recent flurry of teachers strikes in Tehran and other Iranian cities reminds us that disillusionment is producing anger and thus a growing readiness of the man—and woman—on the street to openly challenge the regime. But it seems to me that both sides fully understand that a violent confrontation between the regime and the opposition would probably only benefit the hard-liners, something that both Khatami and Khamanei wish to avoid. If "everything is negotiable in Iran," as the saying goes, we should not be surprised to find that, despite the many obstacles to accommodation, a certain logic that is deeply rooted in the politics of the Islamic Republic will prevail.

Even if reformists and conservatives reach some kind of unsteady accommodation, it is unlikely that such a development will allow for a major alteration in U.S.-Iranian relations. Indeed, given the conservatives’ entirely reasonable assumption that an opening to the United States will strengthen the reformists, the ruling clerics are likely to thwart any major effort to bring about a real rapprochement between Tehran and Washington.

The deteriorating relations between the two countries in the wake of September 11 illustrate that fundamental if disturbing fact. After the attacks in Washington and New York, senior Bush administration officials made statements implying that, if Iran supported U.S. actions in Afghanistan, U.S.-Iranian relations might improve. Aware that the administration had been undertaking a review of those relations in the months before September 11, not a few members of the Iranian foreign ministry suggested that Iran was ready to play ball. Moreover, as I noted above, sensing an opportunity, reformist deputies established a parliamentary committee, one of whose missions was to explore the possibility for an Iranian-American rapprochement.

All this came to naught. Smelling the proverbial satanic rat, Khamanei insisted in October that there never could be any normalization of relations with the United States. His judiciary minister drove this home by warning that any advocates of rapprochement would face charges that carried the death penalty. Khatami soon fell in line, as did other ministers.

That the reformists’ initiative in favor of better U.S.-Iranian relations helped bring about this backlash is of course paradoxical. But this development also offers a telling reminder that, for Iran’s hard-liners, normalizing relations would be tantamount to abandoning one of the key premises of the Islamic revolution. Ever since the initiation of the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan, the conservatives have looked to sabotage any effort to improve such relations.

The dramatic seizure by Israel in early January 2002 of the Karine-A, a vessel packed with 50 tons of armaments that had been loaded by the Iranians for delivery to elements within the Palestinian Authority, certainly smells of such sabotage. After all, several weeks before this event Khatami told the New York Times that Iran backed any solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict acceptable to the "majority of Palestinians." Although from Washington’s perspective this ambiguous formula was insufficient, Khatami’s words probably represented a dire threat from the vantage point of Iran’s hard-liners.

Whatever the sources of the Karine-A affair, one thing is clear: Bush’s subsequent assertion that Iran is part of an "axis of evil" that includes Iraq and North Korea has made life much more difficult for the reformists. Bush’s bellicose language has played directly into the hands of the hard-liners, who have always argued that the "Great Satan’s" ultimate purpose is to topple the Islamic Republic. Washington’s threats have also paradoxically encouraged a rapprochement between Iran and Iraq. Aware of the damage it has done, Washington is now backtracking. Thus, just recently, U.S. Secretary of State Powell asserted that the administration in fact supports the reformists and wants a dialogue with Iran. But given all that has happened, any overt attempt to rescue the reformists from the predicament they now face will only make matters worse. The dust must settle before U.S.-Iranian relations can return to normal.

And what is "normal"? In the coming years the best we can hope for is an uneasy détente, in which both sides pursue quiet conversations about the fundamental issues that still divide them. Beyond this, we probably cannot hope for more. As long as Tehran’s clerics control the levers of power, a breakthrough to competitive democracy at home, or a full and formal reconciliation with the United States abroad, is unlikely. Yet Iran’s domestic politics and foreign relations are not about such extremes. A fuzzy and ever-changing middle ground is more likely: one that will open a few doors and close others, one that will prove as intriguing as it is unsettling.