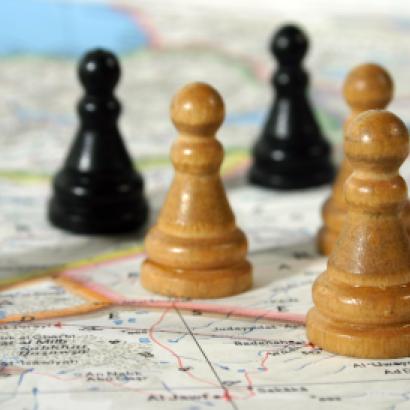

By definition “great games” are complicated with lots of moving parts. Battles on the ground, intense, myriad, and sometimes fratricidal, always connect, however indirectly, to the larger collision of great powers. In Syria, the tug-of-war is a lopsided affair, where Iran, Russia, and the Alawite regime of Bashar al-Assad are invested in winning. The opposing side—Syrian Arab Sunnis, Sunni Gulf Arabs, Israel, the United States, and Turkey—is barely an entente. In the most destructive conflict the modern Middle East has seen (the runner up, the Iran-Iraq war, though comparably lethal, was less destructive to civilians), Tehran and Moscow may not be able to reclaim all of the territory lost by Assad, but they have invested what is needed to regain the most essential parts of the country.

One possible exception: the Syrian north where the Turkish Army has intervened. Ankara has so far been a big loser in the Syrian war. It has likely made its Kurdish problems worse by invading, guaranteeing that it can no longer play Syrian Kurds against each other, and against other Kurds, Damascus, and Tehran. Meddle, divide, and conquer has been the tried and true formula for big power manipulation of this obstreperous minority. Radicalized Turkish Kurds, which once again appear to be growing in numbers, and Syrian Kurds now have an active hatred of a common enemy. Kurdish–Turkish clashes in Turkey have increased since Ankara intervened in Syria in August 2016. The Kurdish problem always has the potential of destabilizing the republic, from Istanbul to Diyarbakir.

The Turkish invasion has given Iran and Russia leverage with Syrian Kurds that is unlikely to decrease, which isn’t the case with America’s support of the Kurds, which is as transient as Donald Trump is fickle. If Ankara decides to stay in Syria to ensure that Syrian Kurds do not develop further cross-border supply lines with their Turkish Kurdish cousins, the paramilitary-cum terrorist Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, it’s unlikely that Russian, Iranian, or Iranian-controlled Shiite militias will attack Turkish soldiers. It’s a near certainty, however, that Assad and his allies will supply the Kurds materiel to bleed the Turks, on both sides of the border. In a battle of wills and military supplies, the Tehran–Moscow–Damascus axis has the upper hand.

Like Turkey, Israel has become a loser in Syria’s Great Sunni Rebellion as Iran has taken control of the Assad dictatorship, which is hamstrung by demographics: even with the massive slaughter and flight of Sunni Syrians, the minority Alawites, a heretical Shiite offshoot, just don’t have the numbers to wage a protracted war over Syria’s 71,500 square miles. The Iranians and their non-Iranian Shiite expeditionary forces have tried to fill the void. Jerusalem is now unavoidably invested in denying the Islamic Republic the means in Syria to launch missiles, a ground war, and terrorist/paramilitary operations against the Jewish State. However, Jerusalem is so far not willing to put Israeli troops into action, using only air power to dissuade its enemies.

Neither has Israel shown any desire to develop a Syrian proxy army, as it once did among the Lebanese Christians. It isn’t clear that the Israelis have the will or the means to prevent the clerical regime from creating a land route from Iran to Hizbollah-controlled Lebanon. Israeli aircraft haven’t once, so far as we know, interdicted Iranian troop and supply planes that travel frequently from Iran and Iraq to the Levant. Israel surely has the intelligence to do so. Jerusalem appears willing so far to play only an aggressive defense, reacting to Iranian and Russian moves. Given the Islamic Republic’s long-standing desire to have a front-row seat in the “resistance” against the Jewish State, given the integral role anti-Zionism plays in the development of Iranian-controlled Shiite militias, a war between Israel and Iran is now likely, in either Syria or Lebanon or both, with a possible exchange of missiles between Israel and the Islamic Republic, and even conceivably Israeli air raids on Iranian Revolutionary Guard–Shiite militia bases inside Iraq and Iran. But Jerusalem will surely try to avoid a regional war for fear of the missiles Tehran has sent to or built in Lebanon.

Israel’s predicament is acute because Washington is willing to do so little. The United States is presently more “in” than Israel in Syria, but its post-Islamic State objectives remain unclear and its resolve appears to be declining. American foreign policy is fundamentally shifting as large slices of the American left and right see intervention abroad as baleful and the Muslim Middle East as too complicated, recalcitrant, and demanding. Washington has developed Syrian proxy armies—the Arab and Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces— for use against the now fading threat of the Islamic State. The Pentagon may keep Special Forces in country to harass remnants of this group and affiliates of al-Qa’ida. How long President Trump will be willing to do that, however, is uncertain. His reluctant decision to stay in Afghanistan likely prevents him from overriding his “instincts” twice. It’s no secret that Trump wants Russian President Vladimir Putin to “handle” Syria. We may assume that Trump sees Putin in Syria and a reborn Islamic State as somehow mutually exclusive even though Russian and Iranian military actions, which haven’t been primarily aimed at the Islamic State, suggest that both see utility in allowing the organization and other radical Sunni groups some running room. The clerical regime has certainly strategically benefited enormously from the Shiite chauvinism that has grown in Arab lands since sectarian conflicts became white hot. Since 2005, when Tehran started aggressively arming militant Iraqi Shiite groups, Iranian influence in the Middle East has expanded primarily through Sunni–Shiite bloodshed.

Senior American officials now talk about a presidentially-dictated 12-month deadline for American ground operations inside Syria. Since the White House has shown no willingness to engage in “nation-building,” which would demand a long-term commitment of US resources to prevent the rebirth of globally-minded jihadists or the conquest of the region by Iranian-led forces, the presence of US troops has diminishing relevance. If the United States were to stay in any strength, American soldiers would perforce start securing the areas in which they operate, directly and through their Syrian partners. “Nation-building” is what American soldiers do if they deploy in numbers with no time-line to depart and no desire to hunker down and watch the neighborhood fall apart.

Against Sunni radicals, the administration is on the verge of adopting “a whack a mole approach,” hoping that the number of globally-minded jihadists is finite and that the risk can be managed through special-forces operations and targeted assassinations. This is Obama redux. So far the administration has been unwilling to provide offensive military support to its Syrian “partners on the ground” in confrontations with the Assad regime and its foreign allies. As telling: where President Trump responded quickly, if not robustly, against the Syrian regime’s use of sarin gas, he has not answered the regime’s repeated use of less lethal chlorine agents.

Assad and his allies constantly probe. The Pentagon has killed Russian, Iranian, and Syrian-regime forces on the battlefield, but this was, most probably, not by design. “Countering Iran is not one of the coalition missions in Syria,” General Joseph Votel, the head of U.S. Central Command, recently told the House Armed Services Committee. If the president keeps his schedule, the American military will soon not engage in defensive actions at all. And fear of global jihadists among the Sunnis will likely be sufficient to keep a withdrawing America from transferring effective anti-aircraft weaponry to Syrian Sunnis to protect civilians and soldiers from devastating Russian and regime air attacks.

What the United States appears to be gearing up to do is to harass Iran, the Lebanese Hizbollah, and the Assad regime primarily through sanctions. Such sanctions are worthwhile. As the recent nationwide anti-regime demonstrations revealed, average Iranians aren’t enamored of the theocracy’s expensive adventurism. The mollahs, their stepchild, the Hizbollah, and their Alawite dependent desperately need more money to maintain the status quo. Denying them the requisite financial means is common sense. Washington is late in developing policies to help the Christian and Sunni Lebanese protect their financial institutions from Hizbollah and to discourage Assad’s cooption of Lebanese banks. Whether the Trump administration can do this now isn’t clear, especially if it decides to maintain the nuclear deal with Tehran. Lots of potentially devastating non-nuclear sanctions are allowed by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (Secretary of State John Kerry regularly told us so). But the “spirit” of the atomic agreement, and European mercantile habits, move us the other way.

The retreat from American hegemony inevitably alters the mentality and analytical capacity of Americans. The unacceptable becomes acceptable. The unthinkable becomes wise. President Obama’s accommodation of the clerical regime (and Russia)—the strained analysis that suggested the nuclear deal would somehow moderate Tehran’s behavior—makes perfect sense if one just wants to put the Middle East in the rear-view mirror. It makes no sense if one believes American retrenchment creates a more dangerous world. In a “great game,” as in checkers and chess, not every confrontation determines victory. But if one loses the wrong pieces at the wrong time, one loses. What is so wry about America’s current disposition is that Washington thinks it can avoid even playing, that it can pick another (easier) battle, somewhere else, to demonstrate America still has red lines. We will see. What always matters most is not how we see the world; it’s how our enemies do.