- World

- Energy & Environment

- History

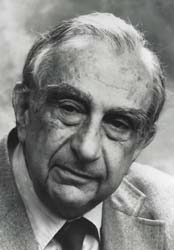

He greets you with a warm handshake, smiles ever so slightly behind a worldly wise face topped with bushy gray brows and silver hair. You have to remind yourself that this charming, articulate gentleman, Edward Teller, is one of the foremost figures of World War II and the Cold War years.

Born in Budapest ninety years ago, Teller did his graduate work in Germany under the brilliant physicist Werner Heisenberg, who was later chosen to lead Hitler’s atomic weapons research program. Teller received his Ph.D. in 1930, but, concerned about the rise of the Nazis, he left Germany in 1933 to work in London and at the famous Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen. Two years later, he moved to America to become professor of physics at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

In 1941, Teller became a U.S. citizen, and the following year he joined the team of Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi, scientists working at the University of Chicago on a top-secret nuclear weapons project known as the Manhattan Project. Three years later, in mid-July 1945, the first atomic bomb was tested in the New Mexico desert. Within a month, two more bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Japan surrendered.

In the decade following World War II, the growing Cold War troubled Teller deeply. During those dangerous years, Teller devoted much of his attention to the possibility of releasing energy via nuclear fusion. President Truman asked his atomic scientists if we should build a fusion bomb—the hydrogen bomb, one thousand times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Among the country’s top nuclear scientists, Teller was the only one who supported the idea. In early 1950, four months after the Soviet Union announced it had successfully exploded an atom bomb, Truman announced his decision to develop the hydrogen bomb to ensure that the United States “is able to defend itself against any possible aggressor.”

Under Teller, the U.S. team continued its work at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in New Mexico. In May 1951, the United States successfully tested the hydrogen bomb at Eniwetok atoll in the South Pacific. Six weeks later, the Soviet Union surprised the Western allies with a proposal for a cease-fire in Korea. An armistice was finally signed in 1953.

Today Teller is director emeritus at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which he launched in 1952 as the nation’s second nuclear research center. He is also a senior research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and has served the nation by advising the Atomic Energy Commission and in many other capacities.

Edward Teller Edward Teller |

One of the first things one sees, in fact, entering his lovely home on the Stanford campus, is a long wooden table displaying a variety of distinguished scientific medals from around the globe. The living room is casually professorial—solid wood furniture with blue upholstery, books and papers piled on tables, souvenirs and art objects scattered about. His portrait, looking sterner than he is, dominates a fireplace of wood and tile.

The brilliant nuclear physicist takes a seat and sips coffee from a mug labeled “I’m the boss. I can do whatever I want.” He sets it down on a tile coaster that reads E = mc2. Quietly he asks, “Now then, what are your questions? What do you want to know?” (It’s immediately clear that the mug speaks the truth. It’s not always clear, however, who’s interviewing whom.)

MUNSON I know your father was a lawyer. What was your mother like?

TELLER My mother lived to quite an old age. She died in her nineties. I’m supposed to be very much like her father, who was even more German than Hungarian. His name was Ignatz Deutsch. My mother was absolutely convinced that I was the reincarnation of her father.

MUNSON Are you married? [Teller holds up two fingers.] Two wives?

TELLER No, no, one wife. Two children. My wife is here. She’s not quite awake. My children are both in their fifties, both married. My son teaches philosophy and my daughter is a computer consultant. I have four grandchildren—now what else do you want to know?

MUNSON Can you actually remember hearing about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand that started World War I?

TELLER Very clearly. We were at the luncheon table. I was six. We heard the news and I was told, “But there will be no war.” I asked the obvious intelligent question, “Why?” They said, “No reason that there should be war.” That left me completely dissatisfied. I still remember that feeling. Two months later there was war. But I remember that conversation where the grownups once again talked nonsense.

MUNSON You met Albert Einstein. What were the circumstances?

TELLER It was a very important meeting. You see, [physicist and Hungarian emigré] Leo Szilard, in 1934, foresaw the military use of atomic energy. Then five years later, the Germans discovered fission. But, in the United States, nothing was happening. So Szilard and another Hungarian physicist, Eugene Wigner, decided to ask Einstein to write a letter to President Roosevelt. They talked to Einstein about it. Leo was brilliant about everything but driving. So he asked me if I could drive him there, which I did. I saw Einstein read the letter (which Szilard wrote), ask a few questions, and sign it. He gave it back to Szilard. Roosevelt received it in October 1939, after Hitler had invaded and destroyed Poland.

The letter was quite effective. It noted that a German research institute had recently discovered nuclear fission and explained that atomic energy could be released in a nuclear reaction, which—in the hands of the excellent German physicists—could give Hitler practically unlimited power. Not long after receiving it, Roosevelt took action, asking the National Bureau of Standards to form a group of scientists to study military uses of nuclear fission.

MUNSON Did the Germans go down a different scientific approach in their search for an atom bomb?

TELLER Yes, to some extent. They went so far as to make a nuclear reactor that used slow neutrons but found it did not work. We did exactly the same thing with slow neutrons, but [Enrico] Fermi and Szilard solved a technical problem—and then it worked. Now, I knew [Werner] Heisenberg well—a very ingenious man, a very wonderful man. The difference between Fermi and Heisenberg was that Fermi wanted to solve the problem and Heisenberg didn’t. All this came out after the war [that Heisenberg and other scientists felt Hitler was a madman and didn’t want him to have atomic weapons].

MUNSON How do you feel today about the future of America? Are you optimistic?

TELLER I’m not an optimist, I’m not a pessimist, I’m a realist. That’s why I’m always right. [A sly peek to see if his kidding is understood. Assured by a smile, he continues.] Look—I do not think that to be successful with Monica is enough. The president should be successful in stakes other than Monica. I don’t mind that he has girlfriends. I do mind that he is inclined to isolationist policies and finding out what the American people want to hear and then telling them what they want to hear. He’s very good at “followership.” We need leadership. In Wilson, Roosevelt, and Truman we had leadership.

MUNSON So you are not optimistic.

TELLER I’m very worried about an antiscientific trend that has developed in the last fifty years. If it continues, I am not an optimist. This is the most important thing I can tell you. When I came to the United States as professor of physics for George Washington University, everything new in science was good. The public had a definite good feeling about progress. Then it changed. What is the name of our excellent vice president?

MUNSON Gore.

TELLER Yes. He feels that whatever scientists are doing, whatever technology is doing, is dangerous. And it’s making the world dangerous. He is taking the leadership of the green movement to save the environment. He is now the greatest green in the world. About that I’m very worried. I’d rather have Monica than the green movement.

MUNSON I have to ask you this: How do you feel about being called the father of the H-bomb?

TELLER It’s nonsense! Many contributed to it. I was one of a thousand contributors. Truman made the right decision. I was the only one who pushed. I did not disown it, and I know my advice got to him. I’m happy about what I’ve done, though it was not easy. It’s recognized in Hungary but not here. The Russians left Hungary, and I know I had a lot to do with that. The Russians would have taken all of Europe and America. Had I not spoken up, we all might be talking Russian.

Let me say one more thing. People believe that the world has become much more dangerous because of the existence of weapons of mass destruction. Let me tell you my version. The world has become much more dangerous for America . . . because today, if anything happens, the United States will be much more seriously involved [that is, exposed to direct attack on our cities by terrorists and other enemies]. Now, with the world getting smaller, we’re as much at risk as Poland was in 1939. I’m afraid of World War III precisely because of people such as Clinton and Gore. They’re too concerned with green issues, they’re not giving real leadership, and they tend to be isolationist in their views.

The big question is What will happen in Russia? The situation is extremely unstable. Almost anything can happen there. We should hear more about it. The Russian people have correctly seen how wrong the prior regime was but have no idea with what to replace it. The United States needs to do more. [He suggests paying for joint projects with Russian scientists.] This is not a popular position, but the Russian scientists are very interested in working with us.

The greatest discoveries of this century are Einstein’s theory of relativity and the discovery of quantum mechanics. In relativity, we learned that you can’t talk about time independent of space. With quantum mechanics, we learned that you can make predictions about the future only by using probabilities.

MUNSON How do you deal with the question of God?

TELLER I will not tell you anything about things I don’t understand. In the nineteenth century, if a physicist believed in God, he had to admit that God is unemployed. He created the world—then the laws of causality determined the future. If today, I choose to believe in God, then, because of quantum mechanics, there is a job for Him—the future is not yet determined.

MUNSON Well, onto a new subject. What scientific discoveries of this century have made the biggest impression on you?

TELLER Look—[long pause] I don’t know what you think about science.

MUNSON I like science.

TELLER What do you like about science?

MUNSON [Challenged] It’s an organized way to look at what we know . . . try out new ideas . . . develop new solutions.

TELLER Look, the most important thing in my mind that science is doing is to provide new ways to look at the world—new ways contrary to common sense. The greatest historical example of this is the discovery by Copernicus that we are moving around the sun about thirty miles per second. He was reluctant to publish it. Are you familiar with the name Arthur Koestler?

MUNSON Yes.

TELLER What do you know about him?

MUNSON He’s a novelist. He wrote Darkness at Noon.

TELLER Yes, he was a Communist who got disenchanted with Stalin. Did you read his book? You must read it. It’s an excellent book because in three-quarters of the book he gives arguments on both sides so that the reader is uncertain as to the author’s point of view. Then, in the last quarter, he comes out completely and definitely against Stalin.

He wrote another book. The title is The Sleepwalkers. It’s about scientists, they are the sleepwalkers. They don’t know where they’re going [long pause] but [triumphantly] the peculiar thing is they get there!

To answer your question, the greatest discoveries of this century are Einstein’s theory of relativity and the discovery of quantum mechanics [a theory involving probabilities that deals with the mechanics of atoms, molecules, and other physical systems]. In relativity, we learned that you can’t talk about time independent of space. Through quantum mechanics, we learned that you can make predictions about the future only by using probabilities. Einstein didn’t accept this work during his lifetime. Now we know it is right. In modern physics, the concepts of time and causality are much less rigid than people used to think. It was quantum mechanics that turned me into a scientist.

MUNSON What pleasant memories stand out in your mind?

TELLER [smiling] Someone once introduced me, saying, “Dr. Teller is from Hungary—which should be obvious because of his remarkable resemblance to Zsa Zsa Gabor.” Years later, I met her. I told her the story and got a kiss.

MUNSON If a reputable scientist wanted to clone you, would you let him?

TELLER If a scientist were crazy enough to want to clone me, probably I would agree. Why not? I do think cloning should be regulated, but nobody should be cloned without his permission. People have a right to their personalities.

MUNSON What new scientific discoveries do you anticipate?

TELLER The greatest discoveries have come as such major surprises, it’s hard to say. I do expect and hope there will be a new discovery about what life is. The idea of what life is has never changed. We need to find out if monocellular life exists on Mars or the moon. The earth is about five billion years old. We know the earth didn’t have any oxygen on it for maybe half of its first five billion years, so human life didn’t exist, but monocellular life probably existed. To say there’s no life on Mars or the moon is not justified; there may be monocellular life.

Life is so far from that part of science we understand. We have to ask ourselves, are there other things as crazy as life that exist?

MUNSON Last questions: If you could talk to American schoolchildren, what would you tell them?

TELLER Don’t be afraid of progress. Do you know what the most inert material in the universe is? It’s the human brain.