- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

The general consensus is that last November’s election was about nothing, an election to determine the outcome of an issue—impeachment—about which few candidates had anything to say. But in fact, like most elections, this one was partly about government. And not so much the federal government in Washington, where deadlock between the parties seems likely to continue, as government at the state level, where real changes have been wrought in the 1990s, changes measured in lower taxes, shorter welfare rolls, and decreased crime.

These changes are wildly popular. Analysts attribute voters’ positive attitudes about the direction of the nation and most politicians to the economy, and surely that is one factor. But welfare and crime are important, too. And they have been declining as steeply as they increased in the awful decade between 1965 and 1975, when welfare rolls and crime tripled. In the last five years, both have been cut by about one-third. These cuts have been almost entirely the work of state and local officials, mostly Republicans.

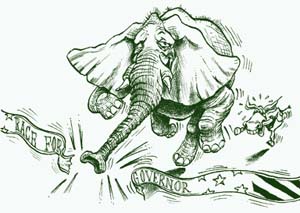

Illustration by Ismael Roldan Illustration by Ismael Roldan |

The result has been—with the conspicuous and important exception of California—a set of smashing victories for Republican governors. The most important victories may well be those that got the least notice on election night broadcasts because they were long expected and overwhelming. In big state after big state, the incumbent Republican governor had no serious opposition: George Pataki of New York, Tom Ridge of Pennsylvania, John Engler of Michigan, Tommy Thompson of Wisconsin, Don Sundquist of Tennessee, and George W. Bush of Texas. Each first won office by a relatively narrow margin in a state where Demo-crats had run serious candidates for many years. Each became so popular that he attracted no real competition. Even Pataki’s opponent, Peter Vallone, though a serious officeholder, failed to run a serious campaign. Some of the other challengers—Geoffrey Fieger in Michigan and John J. Hooker Jr. in Al Gore’s Tennessee—were an embarrassment.

Other victories deserve notice as well. In Connecticut, Governor John Rowland’s tax cuts produced a landslide over Democrat Barbara Kennelly. In Ohio, a lackluster Bob Taft succeeds two-term Republican governor George Voinovich, prolonging one party’s control of the governorship beyond eight years for the first time in ninety-nine years in often-pivotal Ohio. In Illinois, George Ryan exploited splits in the Democratic Party to stretch the Republicans’ hold on the governor’s mansion past twenty-two years. In the race for governor of Minnesota, suburban mayor and former pro wrestler Jesse “the Body” Ventura and St. Paul mayor Norm Coleman held Democratic-Farmer-Labor nominee Hubert Humphrey III to under 30 percent of the vote—exactly fifty years after Humphrey’s father won election to the Senate with 60 percent of the vote and became a national spokesman for Democratic liberalism.

While Washington has spent most of the 1990s in deadlock, real political change has been taking place in the states—in lower taxes, shorter welfare rolls, and a lot less crime.

These victories carry implications for the future of American politics. One is that the Democratic Party, should it lose control of the Lincoln bedroom, has little institutional strength. Where it has strong candidates, it can win impressive victories. But where it does not, it can implode. Second, and more important, last November’s gubernatorial victories show that Republicans elected by narrow margins and championing policies attacked by Democrats and editorial writers can build a consensus when they put those policies into effect. Examples: Pataki and tax cuts, Engler and welfare and education reform, Thompson and welfare reform, Sundquist and tax cuts, Bush and tort reform and welfare reform. Even the editorial writers ended up endorsing them. In state after state, there is a consensus on public policy, forged by once-controversial Republicans, which is considerably to the right of the consensus Bill Clinton has hoped to forge nationally.

What about the Democrats’ wins in South Carolina and Alabama? They can both be attributed to the popularity of outgoing Georgia Democratic governor Zell Miller’s lottery, whose proceeds pay for college scholarships. Interestingly, this is an economically regressive plan: Lottery players are mostly low income, and scholarship winners tend to come from middle- and upper-income households. But the plan’s popularity is proof that voters are less interested in progressive taxation than in rewarding students’ merit. That is encouraging for Republicans as well as New Democrats.

And what about California, where former Republican governor Pete Wilson was term limited? Dan Lungren, the Republican candidate, spent most of his fall advertising funds on the crime issue, hoping to establish that Democrat Gray Davis was as much of a squish as his boss of twenty years ago, Jerry Brown. But Davis was too smart to let that label stick. Meanwhile, Lungren had relatively little to say about education. Over the last twenty-five years, while Democrats allied with teachers’ unions, the schools of education and Sacramento bureaucrats have had custody of California’s public schools. During this period, California has seen its test scores plunge from among the top ten in the nation to number forty-nine. But it was Davis who emphasized education reform, with a serious program crafted to be minimally unacceptable to the teachers’ unions. The result proves not that California voters are unready for radical change but that the Republican nominee was uninterested in providing it.

The lesson for 2000 is clear. Republicans should not be afraid of championing radical reform. Voters want reform, even radical reform, of governmental institutions that aren’t working, but that reform needs to be conciliatory, not confrontational, in tone.