- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

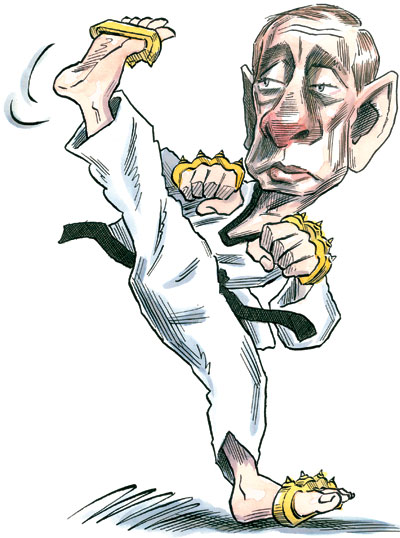

Most people made up their minds about Vladimir Putin soon after he became Russian president in April 2000. To do this, they had no need to exercise the arcane skills of Kremlinologists. They simply had to switch on their televisions and take a look at him. He had none of Mikhail Gorbachev’s civilized manners or Boris Yeltsin’s boozy drôlerie. There he was, a pugnacious little fellow with an impassive face, ever ready to take offense. His fists were habitually clenched and he exuded a barely contained fury, visibly conveying his restlessness to get things done in precise compliance with his commands. It is an impression that has lasted.

There is little doubt about who has orchestrated the strategy for the recent and audacious acts of Russian belligerence. Putin has pulled off the gloves in the past several months. His submariners have planted Russia’s flag on the Arctic ocean bed, signaling a determination to secure national rights to oil and gas exploitation there. Russian warplanes recently infringed upon British airspace and had to be escorted out of it by Royal Air Force fighters. Putin has demanded that American plans to set up anti–ballistic missile bases in the Czech Republic and Poland be scrapped. He has threatened to permanently suspend his country’s observance of the Conventional Forces in Europe treaty if the United States refuses to back down. When Alexander Litvinenko was murdered in London in November 2006, Putin took umbrage at foreign suspicions that his security agencies were behind the crime; the condolences he extended to the victim’s family were perfunctory, his face an iceberg of formality. Soon afterward, Putin raised hackles in Washington by suggesting that a Kazakh rather than an American should be the next head of the International Monetary Fund. And as for the recent pictures of him, bare-chested and fishing in Siberia . . .

Vladimir Putin’s self-righteousness has gone down well with most Russians. They feel that Gorbachev and Yeltsin yielded too much and too often to foreign powers and, moreover, that Yeltsin embarrassed them.

This is a Russian president bursting with confidence. Putin aims to protect and enhance Russia’s position in the world on the foundation stone of his own values. He also intends to remain the national leader. Until September 2007, he dutifully stated that the Russian constitution ruled out a third term in office. His friends encouraged him to push a constitutional amendment through the Federal Assembly, but he resisted this appeal to meddle with the post-Soviet order. Now we know why. Suddenly, he announced his move: he would step down as president and move across to the post of prime minister. He made it clear that he would not expect to behave subserviently to the new president—and evidently the person who becomes president will be his choice. True, there will be a contested election, but no one believes that Putin’s protégé, with unmatchable support from business and the media, will fail to win. The other contenders will know this. Russia, at the moment and for the foreseeable future, has a closed political system, and Putin is its gatekeeper and chatelain.

Seven years ago, it was a different story. Then, Putin was careful to pay lip service to democracy and the rule of law. This was how every ruler in Russia had talked since Gorbachev in the last years of the Soviet Union. Russian liberals were never fooled, but, alas, leaders from North America and Europe rushed to pay their respects. Everybody, it seemed, wanted to be friends with Vladimir Putin and sought out his chummy side.

He went along with this charade for as long as it suited him. The Russian economy, at the time he became president, was still recovering from the financial collapse of August 1998. The war he had restarted in Chechnya a year later, when he was still only Yeltsin’s prime minister, was not going well. The billionaire oligarchs who had paid out vast sums to Yeltsin to prop up Russia’s postcommunist system continued to exercise an uncomfortable amount of public influence. Putin, furthermore, was still feeling his way in global politics. Yet it did not take long for him to exhibit what he truly thought of his peers. His scorn for Tony Blair’s attempt to justify the invasion of Iraq was advertised at a Moscow press conference in April 2003: “Where are the arsenals of weapons of mass destruction, if they ever existed?” Blair stood by his side, unable for once to summon up a smile. Putin was equally sharp-tongued with President Bush in St. Petersburg in July 2006. Speaking in his native city, Putin turned to the American president and said, “I’ll be honest with you: of course we would not want to have a democracy as in Iraq.” Bush tried to interject: “Just wait—.” But Putin was in no mood to wait, snapping, “Nobody knows better than us how we can strengthen our nation!”

This self-righteousness has gone down well with most Russians. They feel that Gorbachev and Yeltsin yielded too much and too often to foreign powers—and that Yeltsin’s buffoonish antics embarrassed the whole country. Putin, by contrast, lectured Blair, Bush, and Chirac whenever they tried to impress on him the need to foster democracy, civil society, and peaceful resolution of conflict. Like the veteran Leningrad judo champion that he is, Putin gets his blows in first. In his latest annual address to the Federal Assembly, in April 2007, he abandoned the pretense of aiming to place political elections or judicial trials on a fairer footing. This was Putin the authoritarian at his most rampant.

His evident objective is to consolidate the system of power that so suits him and those with whom he rules. He heads and promotes a group drawn predominantly from the old KGB. It has been calculated that about threefourths of the highest public officeholders in Russia today have either worked for the security agencies or been closely associated with them. Putin is a KGB man through and through. He toiled as an official for the notorious security agency in East Germany, before returning to Leningrad in 1990. As such, he never experienced the liberating aspects of Gorbachev’s perestroika at firsthand. Putin has referred to the dismantling of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 as “the greatest political catastrophe” of the twentieth century. The Communist Party was banned by Yeltsin for a few years, but the KGB’s successor organization, the FSB, preserved KGB morale, personnel, and procedures throughout the 1990s. And while working in the St. Petersburg civil administration during that decade, Putin maintained contact with his old comrades.

At the same time, Yeltsin was taking note of this dapper young man’s attentiveness to detail. He was impressed by his courtesy and admired his willingness to take the initiative. Perhaps Yeltsin in his dotage saw Putin as a more restrained incarnation of his own younger self, and when he stepped down at the end of 1999, Yeltsin spoke of him as of a beloved son. Yeltsin had already drawn Putin from the shadows, making him director of the FSB in July 1998; barely a year later, Putin was promoted to prime minister. As he rose up the ranks, he won the trust of the circle of ultrawealthy businessmen whose influence over Yeltsin’s Kremlin was at its height. These oligarchs had amassed Midas-like fortunes by scooping up the rights to Russian natural resources in the privatization process of the mid-1990s.

Among them was Boris Berezovsky, who came to regard the polite Petersburger as his protégé and bragged about having put him forward to Yeltsin for the premiership. But Berezovsky and his ilk badly misjudged Putin, who has gone on to bully every oligarch who dared to interfere with his presidential prerogatives. Those businessmen who don’t toe the line in Putin’s Russia end up in a penal labor colony, like Mikhail Khodorkovsky, or in exile, like Boris Berezovsky in London and Vladimir Gusinsky in Spain. Putin’s battle with the oligarchs is manifested in the drastic changes he has brought about in Russian economic policy: the state has wrested back control of the most profitable companies, especially those in the energy sector, often by assigning security-agency personnel to their boardrooms. Ostensibly these appointees are no longer FSB employees, but, as the Russian saying goes, “There is no such thing as a former Chekist.” (The Cheka under Lenin was the forerunner of the KGB and the FSB.) The effects have been remarkable. State enterprises as recently as 2003 controlled only 20 percent of Russian business interests. Today, the portion is 35 percent and rising.

Putin has pulled this off with cunning. He has focused publicity on the humiliation of greedy oligarchs, and popular opinion has responded favorably. Yet the “securitocrats” are as rapacious as the oligarchs once were; they love money and hate those who try to prevent them from getting their hands on it. Few Russians know the truth of this because they get their news overwhelmingly from TV stations, all of which either are state-owned or operate in fear of upsetting Putin. Only the most courageous journalists have broken free from this cage of news manipulation. There has been a sequence of murders of reporters, culminating, infamously, in the shooting of Anna Politkovskaya in October 2006.

So relentlessly has Putin imposed his iron will both at home and abroad that it’s easy to forget that, when he took power, there were cracks in the edifice of his official image. Journalists who interviewed his acquaintances in St. Petersburg dug up some revealing stories. Female school friends remembered him as having been altogether uncomfortable with girls. There was also the tale, never denied, that as an adolescent he had applied for employment by the KGB. Even for a teenager fervently dedicated to the Soviet cause, this was exceptional. As the Leningrad office explained to him, it was the KGB who invited individuals to join and not the other way round. But the feared security agency eventually did issue the invitation when checks on his background and behavior confirmed him to be a sound Soviet patriot. Putin spent as much time studying Leninism and training for judo as he did studying for his law degree. Competent, resourceful, never hogging the limelight, he was recognized as well fitted to become a security policeman—indeed, he was the perfect modern Chekist.

Boris Berezovsky and his ilk badly misjudged Putin, who has gone on to bully every oligarch who dared to interfere with his presidential prerogatives.

This was fine until the era of open politics beckoned in Russia, and then it was no longer enough to be talented in behind-the-scenes maneuvers. Suddenly, first as prime minister and then as president, he had to cope with the media, and there was no more difficult period in his entire career. In the summer of 2000, he was widely criticized when he declined to visit the families of victims in the Kursk submarine disaster. He appeared shockingly lacking in compassion. Nor did he improve his image when it became known that his favorite pet was a poodle called Tosya. (Russian males are not taught to explore their “feminine side,” and Putin’s fondness for Tosya made him seem a bit of a wimp.)

Today, the presidential website is better attuned to popular sensibilities. Ownership of Tosya is now ascribed to his wife, Lyudmila. Putin’s personal dog, Koni, is a black Labrador, plainly a canine companion more appropriate to a man’s man. Indeed, the president recently rebuked an entire press conference for pampering the dog: “Sometimes Koni leaves a room full of journalists with a very pleasant expression on her face and biscuit crumbs around her mouth.” His ascetic traits of character are endlessly emphasized. His wife and the rest of the family get to speak to him only at the end of a long day when he takes his regular nightcap, a cup of yogurt. (No alcoholbased indulgence for the man of steel.) Russians were disconcerted on hearing that Raisa Gorbachev expressed forceful opinions and thrust them on her husband. There is no hint of this with Lyudmila Putin.

Competent, resourceful, never hogging the limelight, Putin was well fitted to be a security policeman—indeed, he was the perfect modern Chekist. Today, he has expanded his repertoire.

Recently his public-relations office has made him appear less dour than such characteristics might imply. In August, he went on a trip to the Tuva republic in Siberia, accompanied by Prince Albert of Monaco. Some sixty photos were taken of the president at play; he was photographed bare to the waist while angling in the local rivers, looking as fit as a flea. The photos appeared on the presidential website, and many women wrote in to express their appreciation. (Perhaps men did, too—if so, this remains a carefully guarded secret.) Putin is by far and away the favorite living figure for Russian citizens, scoring a 75 percent rating of “good” or “excellent” in an opinion survey conducted in July. This is impressive for a politician now in his eighth year of power in a country where more than a fifth of the population languishes below the U.N. poverty level. Putin’s popularity is all the more astonishing when one accounts for the ongoing scandals of political corruption and judicial abuse—not to mention the trauma caused by his disastrous war in Chechnya.

What chiefly appeals to his fellow Russians is his success in striding out onto the world’s stage on their behalf. His countrymen love his touch of menace, as when he stated, “A few years ago, we succumbed to the illusion that we don’t have enemies, and we have paid dearly for that.” His perfunctory expression of condolence for the gruesome assassination of Alexander Litvinenko in London was interpreted in the same way. Yet again the president refused to kneel before global opinion.

The point for most Russians is that Putin is not merely a patriot but a brutally effective patriot. In the early 1990s Russia, once an industrial power mightier than any rival except the United States, was aghast to see its gross domestic product slump beneath that of Belgium. Today, it has the eighth-largest economy in the world and a renewed self-confidence. Ever the optimist, Putin promises that more improvement is to come.

In his 2007 Federal Assembly address, he indicated several immediate priorities: transport by road, rail, and river will be upgraded; oil-refining facilities will be updated; a Russian nanotechnology corporation will be founded. Putin also called for the continuing modernization of the armed forces, which everyone knows are in shoddy condition. There have been worries, in Russia and abroad, that nuclear facilities are not being looked after with due care; Putin, though, has taken pride in getting his warplanes aloft again, complete with their nuclear payloads. He stresses that Russia has only pacific intentions, but the days are gone when the country meekly submitted to calls to renounce its global ambitions.

If Putin were able to stand again for the presidency, he would definitely win. This is an exceptional achievement. No Kremlin leader since the 1960s—not Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev, or Yeltsin—was much grieved over when he left high office. Putin will be the exception. In September 2007, Putin appointed the obscure Viktor Zubkov—another fellow who made his career in Putin’s St. Petersburg—as prime minister, and in December Putin declared him his favored candidate for president. The winning candidate will know in advance that Putin’s legacy has to be conserved. Even if Putin decides not to move across to the post of prime minister, his successor would find it hard to disestablish his settlement of the Russian political order, even if he were so inclined.

Future generations of Russians may well judge Putin more harshly. Turning Chechnya into a slaughterhouse has not solved the dilemmas of national security. He has not found a path for comprehensive economic development. Without the lucky surge in oil and gas prices at the beginning of his first term, Russia would remain submerged in macro–financial trouble. The country has a badly distorted democracy. The clamps on civil society are severe. There are, as yet, few signs of discontent; the Russian poor, millions of them, are too sunken in morale to rebel.

The point for most Russians is that Putin is not merely a patriot but a brutally effective patriot. Future generations, however, may well judge him more harshly.

But the West should be in no doubt that it is going to find Russia a handful in the years ahead. Russian energy sources will become an instrument of political pressure, especially on the European Union and countries of the old Soviet bloc. This does not mean that a new Cold War is at hand; Putin and the securitocrats know that Russia’s future lies with the market economy and that peace, rather than military conflict, is essential for the country’s future prosperity. That much is a blessing for the rest of us. But the outgoing president leaves a worrying legacy: his terms in office have raised Russia back into global political and economic influence at the price of exacerbating tensions with other countries.

Putin has always enjoyed catching the world off guard, and he appreciates the advantage of remaining an enigma as a person and a leader. The pictures of him fishing in Siberia and walking his Labrador are publicity ploys. Nobody, even now, knows much about how he handles his ministers or plots his strategy. His declaration of interest in becoming prime minister is just his latest surprise. One thing is certain: when he writes his memoirs, the ex-KGB man will not disclose the many secrets he harbors. Once a Chekist, always a Chekist.

A version of this essay appeared in the Independent (U.K.) on September 9, 2007.