- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- US Labor Market

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Economic

- Contemporary

- World

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- Congress

- History

In 1968, the American ecologist Garrett Hardin wrote “The Tragedy of the Commons,” which must be the most cited article ever to appear in Science. In this article, Hardin described the “tragedy” associated with common pool resources—those that are claimed or used by many with little effective restriction. With a common resource, each party is motivated by private self-interest in deciding how much of a resource to use, and when. But the costs of these private decisions are spread across to everyone. This mismatch between private and social benefits and costs in decision making results in the outcomes we are all familiar with—waste, plundering, and extensive and rapid use of the resource with little consideration of the future.

Hardin made his point by describing a pasture that was open to all, and hence subject to overgrazing. Although each herder privately benefits from grazing his or her own animals, all herders share the costs of overstocking. Under these circumstances, each herder is motivated to add more animals than would be optimal for the range resource. Hardin concluded: “Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.”

Although Hardin was eloquent in describing the problem, he was much less persuasive in describing the solution. The remedy he offered was “mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon . . . coercive devices to escape the horror of the commons.” According to Hardin, the outcome would be unjust because some parties would accept more costs and fewer benefits than others. Why? “The alternative of the commons is too horrifying to contemplate. Injustice is preferable to total ruin.” Of course, Hardin was wrong—not in identifying the underlying source of the tragedy of the commons but in predicting its solution.

All around us we see examples of cases where common pool resource problems persist, at least until there is a major crisis. Parties disagree, occasionally on the magnitude or nature of the overall problem but most often on the sharing of the costs and benefits of addressing it. These distributional issues block agreement, and the problem of open access continues. Fairness does matter, and few are willing to shoulder more of the costs than others to address the losses of the commons. And if compliance cannot be monitored and ensured, then even if some parties agree to bear more of the burden, little will come of this action because others will continue to use or exploit the resource. Self-restraint under a commons does not pay—for the individual or for the resource. Accordingly, the problem continues.

At some point a crisis occurs—the pasture is so overgrazed that it no longer supports any livestock, and all herders lose. With a crisis, the status quo is no longer viable, and distributional issues become less critical in agreeing to a solution to the problem of open access. But by that time, the resource may be so depleted and the crisis so severe that the resource cannot rebound. Hence, the tragedy of the commons.

Fortunately, in many cases, conditions are not so dire, and recovery is feasible if effective solutions can be found. The lesson, however, is that remedies do not come early but late. They may come too late in some important cases to avoid the losses of the tragedy of the commons.

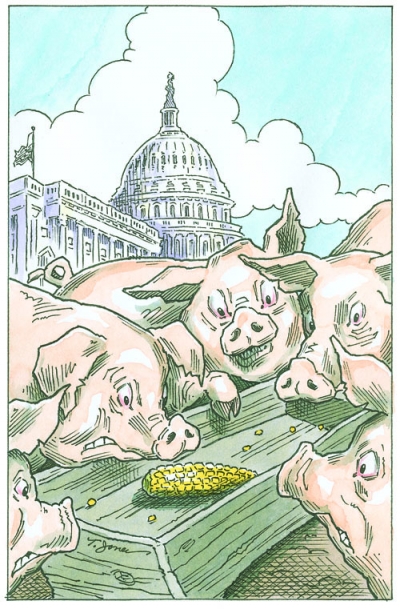

So, what does the tragedy of the commons have to do with the floundering efforts to save the euro and the failed U.S. government debt negotiations? The answer is that they are both examples of commons problems. Consider the U.S. federal debt. The federal government budget is a common pool resource—that is, the president and each member of Congress seeks a portion of it to advance particular preferred policy objectives and to reward valuable constituents. There is not enough in the budget to satisfy all of these 536 claimants (the president and the members of the Senate and House). Expanding the budget requires raising taxes, borrowing, or both. Higher taxes are unpopular, so in recent years borrowing has increased.

From 1980 onwards, U.S. debt has generally risen toward levels not seen since World War II. Indeed, the debt load has become high enough that credit agencies have begun to doubt the ability of the United States to credibly pay it off. On August 6, 2011, Standard & Poor’s lowered the United States’ AAA credit rating.

Despite growing concern about the debt, members of Congress and the president have not been able to reach agreement about how to lower it. On November 21, 2011, the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (the so-called Super Committee) failed to come up with a resolution. Politicians from both parties were unwilling to raise taxes or to cut expenditures sufficiently to reduce federal borrowing. As Hardin would explain, each politician seeks to protect his or her private political interests and agendas, even though the overall U.S. economy will likely be harmed, as will its ability to rebound from the recession. Politicians could not agree on a sharing of the costs (higher taxes and expenditure cuts affecting their constituents) for the benefit of reducing the federal debt.

What about the euro? In January 1958 six European countries joined to form the European Common Market with reduced tariffs and more-integrated economies. In 1993 the European Union (EU) was formed. By 2007 the EU had twenty-seven members and five other European countries as candidates. A common currency, the euro, was introduced in 1999, with seventeen of the EU member countries adopting it.

The euro seemed to be a logical progression in the gradual uniting of European economies. It lowered transaction costs in trade and reduced borrowing costs in at least some member countries because debt was denominated in euros, rather than in local currencies such as the drachma. This not only facilitated the writing of debt instruments but also appeared to lower default risk. The euro was Europe’s currency and it began to compete with the dollar as the international currency for exchange. After a slow start, the value of the euro rose beyond par with the dollar. Everyone seemed to benefit. German and Dutch exporters sold more to Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Italy, and Europeans could more easily travel throughout the continent, with northern Europeans purchasing vacation homes on the Mediterranean.

While linked monetarily, the eurozone countries were not bound by a common fiscal policy. Expenditures, taxes, and borrowing patterns diverged. Indeed, the euro promoted higher debt levels. The euro became a common pool resource. So long as its value was ensured, eurozone countries and their populations could borrow at low rates and expand both private and government expenditures. The problem, of course, was that the fiscal policies of the countries within the eurozone varied dramatically. It was rational for politicians in some countries to borrow more and increase debt, relying upon the common currency. As long as their economies continued to grow, there was no emergency.

But debt levels grew, especially after the financial shocks of the late 2000s. By 2011 debt levels in Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and possibly France became so high that sovereign default was possible. But just as with other tragedies of the commons, members of the eurozone have not been able to devise a credible solution. Politicians from northern Europe are reluctant to saddle their thrifty taxpayers with the debts of their spendthrift southern neighbors. This is despite the fact that should countries default and the euro fail, there are likely to be severe economic repercussions, affecting everyone, including those in northern Europe who profited from exporting to southern Europe during the euro boom. The parties cannot agree on the sharing of the costs and benefits of guaranteeing the debt of all eurozone countries. Here, too, is a potential tragedy of the commons.

As stated by Garrett Hardin, the alternative to the losses of the commons may be so “horrifying” that some agreement among the eurozone countries is ultimately reached. This would be propelled by an imminent crisis. In the case of the euro, the current crisis may lead to greater efforts to protect the currency. The costs of doing so, however, are very high because it requires actual coordination and control of sovereign fiscal policies, something national politicians and their constituents are loath to relinquish.

In the case of U.S. debt, the solution could be easier, because other sovereign countries are not involved. Rather, individual politicians represent jurisdictions within a single country. Taxes could be raised and expenditures could be reduced. But a crisis at home has yet to materialize to push politicians to such agreement. The tragedy of the commons may yet unfold.