- History

- Military

President Trump’s remarks about the need to “restore patriotic education” at the White House Conference on American History have provoked a flurry of defenses and counterattacks from academic historians. The defenders dispute the notion that their teaching undermines patriotism, contending that any criticisms they might make of the United States are intended to improve the United States, not destroy it. The counterattackers denounce the President for threatening their academic freedom and advancing a version of history that ignores racism and pays too much attention to dead white males.

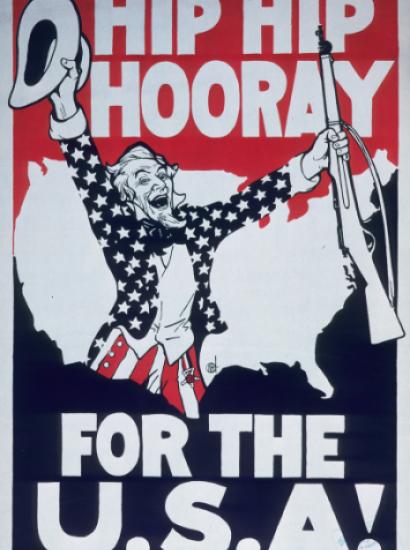

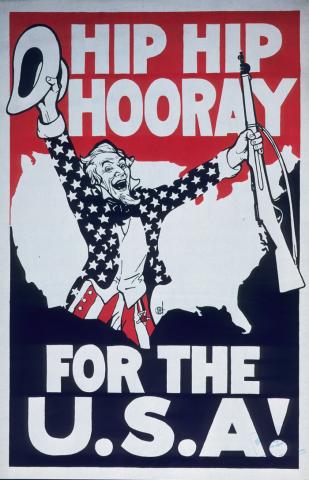

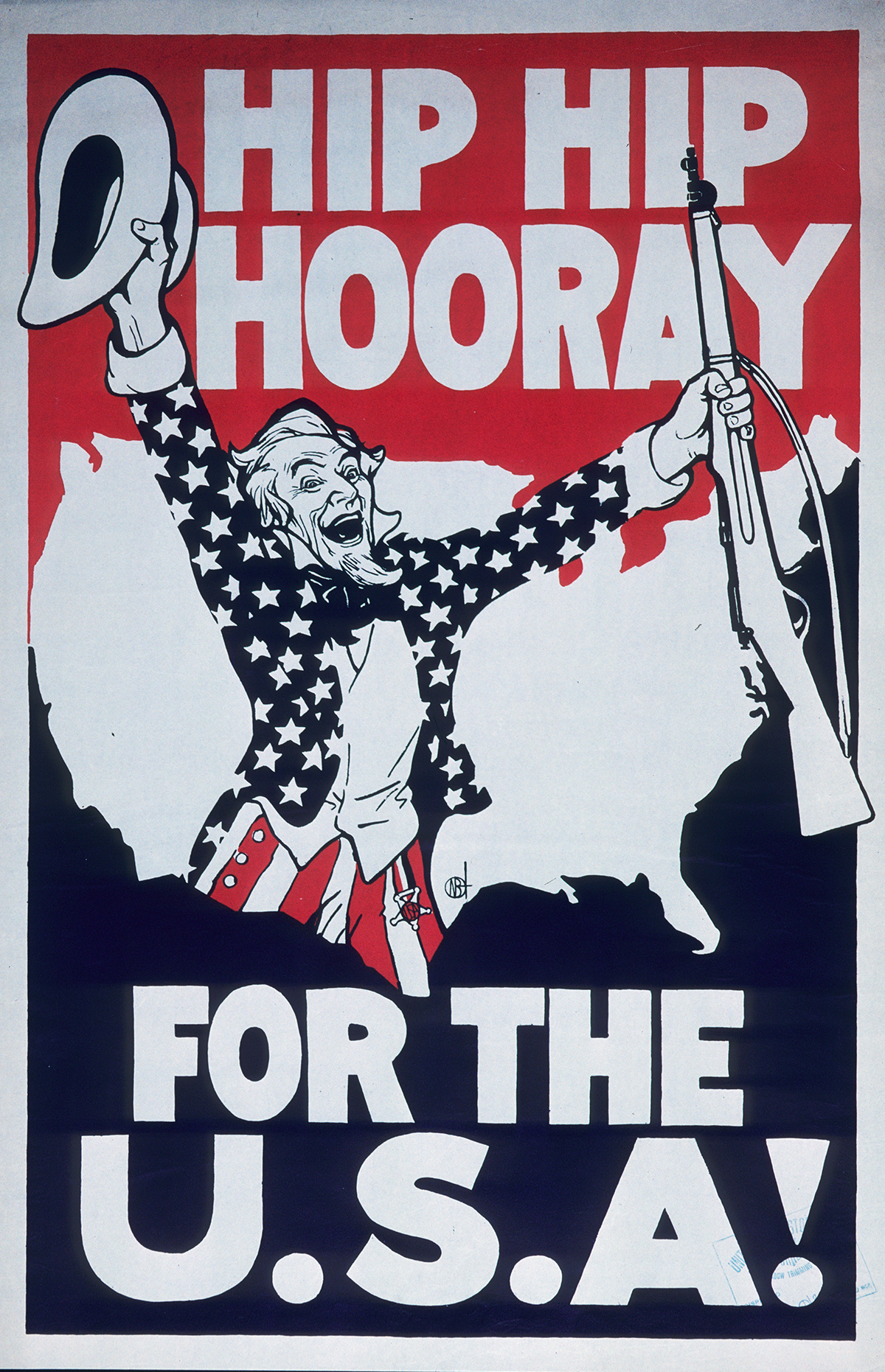

Military history features prominently in the debate over the role of patriotism in history education. The flourishing of the historical profession in the United States in the nineteenth and earlier twentieth century was accompanied by a strong interest in military history and in the use of history to promote patriotism, epitomized by Theodore Roosevelt, who in addition to his duties as an army reserve colonel and President of the United States also served as President of the American Historical Association and wrote several books on naval history. To the historians of these times, military history provided heroes whose patriotic examples would inspire patriotism in other Americans, and it offered lessons for the use of military power by a virtuous nation.

Military history continues to captivate the American people, as is readily apparent from the popularity of books on the subject. The profession of military history, however, has disappeared almost entirely from the history departments of America’s colleges and universities. Departments that still offer military history courses—typically in response to demands from administrators that courses attract more than a few students—typically hire adjunct professors, who teach large courses for a pittance.

There are still historians at colleges and universities who write about military history, but they do so by specializing primarily in other topics and avoiding positive references to the military prior to receiving tenure. These historians recognize the absurdity of the argument that military history promotes militarism, and many of them are themselves wary of the military and the use of history to promote military service or patriotism. In the toxic political atmosphere of academic departments, however, they may come under fire for insufficient commitment to the causes of the Left. As John McWhorter recently wrote in the Atlantic, complaints about campus politics no longer come mainly from conservative professors (they now are mostly gone) but from “people left-of-center wondering why, suddenly, to be anything but radical is to be treated as a retrograde heretic…. It is now no longer ‘Why aren’t you on the left?’ but ‘How dare you not be as left as we are.’”

The shunning of military history began during the Vietnam era, when students and junior faculty blamed nationalism and militarism for the alleged wrongs of the Vietnam War. Harvard historian Jill Lepore recently observed that the history of the American nation fell into decline among the faculty because “hatred for nationalism drove American historians away from it.” Political history and diplomatic history lost influence, but the field to suffer the most was military history, as it was deemed to be especially closely associated with nationalism and militarism.

President Trump is right to demand that history education be overhauled to promote patriotism and remove harmful influences like the 1619 Project. Reviving military history should be an important part of that endeavor, for the same reasons that it was part of historical education in earlier times. Given the current state of American academia, the endeavor will have to be driven by politicians, parents, and other citizens at the national, state, and local levels who recognize that young Americans are not receiving the education they deserve.