- International Affairs

T

here is Europe and there is "Europe." There is the place, the continent, the political and economic reality, and there is Europe as an idea and an ideal, as a dream, project, process, progress toward some visionary goal. No other continent is so obsessed with its own meaning and direction. These idealistic visions of Europe at once inform and legitimate and are themselves informed and legitimated by the political development of something now called the European Union. The very name European Union is itself a product of this approach. For a union is what it’s meant to be, not what it is.

|

|

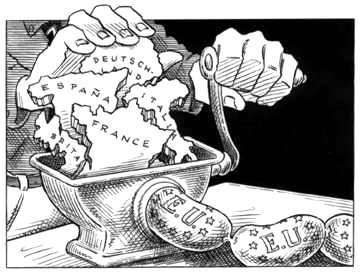

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest. |

European history since 1945 is told as a story of unification—difficult, delayed, suffering reverses but nonetheless progressing. Here is the grand narrative taught to millions of European schoolchildren and accepted by Central and Eastern European politicians when they speak of rejoining “a uniting Europe.” Meanwhile, Western European leaders have repeatedly reaffirmed the goal of “ever closer union” since it was first solemnly embraced in the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

The latest chapter in this grand narrative is even now being written. Its millennial culmination was achieved on January 1, 1999, with a monetary union that will, it is argued, irreversibly bind together some of the leading states of Europe. This group of states should in turn become the “magnetic core” of a larger unification.

European unification is presented as a necessary, even an inevitable, response to the contemporary forces of globalization. Nation-states are no longer able to protect and realize their economic and political interests on their own. They are no match for transnational actors such as global currency speculators, multinational companies, or international criminal gangs. Both power and identity, it is argued, are migrating upward and downward from the nation-state: upward to the supranational level; downward to the regional one. In a globalized world of large trading blocs, Europe will be able to hold its own only as a larger political-economic unit. Thus Manfred Rommel, the popular former mayor of Stuttgart, declares, “We live under the dictatorship of the global economy. There is no alternative to a united Europe.”

It would be absurd to suggest that there is no substance to these claims. Yet when combined into the single grand narrative of European unification, they result in a dangerously misleading picture of the real ground on which European leaders will have to build at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In fact, what has already been achieved in a large part of western and southern Europe is a new model of liberal order. But this extraordinary achievement is itself now under threat precisely as a result of the forced march to unity. Instead, what we should be doing now is to consolidate the liberal order and to spread it across the continent. Liberal order, not unity, is the right strategic goal for European policy in our time.

|

The very name European Union is itself a product of wishful thinking. For a union is what it is meant to be, not what it is. |

The European Monetary Union Gamble

Economists differ, and a noneconomist has to pick his way between their arguments. But few would dissent from the proposition that the European Monetary Union is an unprecedented, high-risk gamble. As several leading economists have pointed out, Europe lacks vital components that make monetary union work in the United States. The United States has high labor mobility, price and wage flexibility, provision for automatic, large-scale budgetary transfers to states adversely affected by so-called asymmetric shocks, and, not least, the common language, culture, and shared history in a single state that make such transfers acceptable as a matter of course to citizens and taxpayers.

Europe has low labor mobility and high unemployment. It has relatively little wage flexibility. The EU redistributes a maximum of 1.27 percent of the GDP of its member states, and most of this is already committed to schemes such as the Common Agricultural Policy and the so-called structural funds for assisting poorer regions. It has no common language and certainly no common state. Since 1989, we have seen how reluctant West German taxpayers have been to pay even for their own compatriots in the East. Do we really expect that they would be willing to pay for the French unemployed as well? The Maastricht Treaty does not provide for that, and leading German politicians have repeatedly stressed that they will not stand for it. The minimal trust and solidarity between citizens that is the fragile treasure of the democratic nation-state does not, alas, yet exist between the citizens of Europe, for there is no “united public opinion,” to recall Mill’s phrase.

Against this powerful critique, it is urged that “asymmetric shocks” will affect different regions within European countries and that the countries themselves do make provision for automatic budgetary transfers. In France, it is very optimistically suggested that reform of the Common Agricultural Policy and “structural funds” will free up EU resources for compensatory transfers. (But if we are serious about enlargement, some of these resources will also be needed for the much poorer new member states.) European supporters of free markets argue that monetary union will simply compel us to introduce more free market flexibility, not least in wage levels. Yet none of this adds up to a very persuasive rebuttal, especially since different European countries favor different kinds of responses.

The dangers, by contrast, are all too obvious. The EMU requires a single monetary policy and a single interest rate for all. What if that rate is right for the German economy but wrong for Spain and Italy or vice versa? And what if French unemployment continues to rise? As elections approach, national politicians will find the temptation to “blame it on the EMU” almost irresistible. If responsible politicians resist the temptation, then irresponsible ones will gain votes. And the European Central Bank will not start with any of the popular authority that the Bundesbank enjoys in Germany. It starts as the product of a political-bureaucratic procedure of “building Europe from above,” which is even now perilously short of popular support and democratic legitimacy.

Giving Up the Deutsche Mark (Painfully)

Take the case of Germany—Europe’s central power. It would be hard to dispute the simple statement that since 1989 Germany has reemerged as a fully sovereign nation-state. In Berlin, we are witnessing the extraordinary architectural reconstruction of the grandiose capital of a historic nation-state. Yet, at the same time, Germany’s political leaders have pressed ahead with all their considerable might to surrender that vital component of national sovereignty—and, particularly in the contemporary German case, also identity—which is the national currency. There is a startling contradiction between, so to speak, the architecture in Berlin and the rhetoric in Bonn.

I do not think this contradiction can be resolved dialectically, even in the homeland of the dialectic. In fact, Germany today is in a political-psychological condition that can be described only as Faustian: “Zwei Seelen wohnen, ach, in meiner Brust” (“Oh, two souls live in my breast”). Now that monetary union has gone ahead, the country woke up in its new bed on January 1, 2000, scratched its head, and asked itself, “Now, why did we just give up the deutsche mark?”

|

Since 1989, we have seen how reluctant West German taxpayers have been to provide unemployment benefits, even to their own compatriots in the East. Do we really believe they would be willing to pay for the French unemployed as well? |

What is the answer? Of course there are economic arguments for monetary union. But monetary union was conceived as an economic means to a political end. In general terms, it is the continuation of the functionalist approach adopted by the French and German founding fathers of the European Economic Community: political integration through economic integration. But there was a more specific political reason for the decision to make this the central goal of European integration of the last decade. As so often before, the key lies in a compromise between French and German national interests. In 1990, there was at the very least an implicit linkage made between François Mitterrand’s anxious and reluctant support for German unification and Helmut Kohl’s decisive push toward European monetary union. “The whole of Deutschland for Kohl, half the deutsche mark for Mitterrand,” as one wit put it at the time. Leading German politicians will acknowledge privately that monetary union is the price paid for German unification.

So Germany, this newly restored nation-state, has entered monetary union full of reservations, doubts, and fears.

The Coming Crisis?

In fact, received wisdom in EU capitals is already that the EMU will sooner or later face a crisis: perhaps in 2001 or 2002 (just as Britain is preparing to join). Euro-optimists hope this crisis will catalyze economic liberalization, European solidarity, and perhaps even those steps of political unification that historically have preceded, not followed, successful monetary unions. A shared fear of the catastrophic consequences of a failure of monetary union will draw Europeans together, as the shared fear of a common external enemy (Mongols, Turks, Soviets) did in the past. But it is a truly dialectical leap of faith to suggest that a crisis that exacerbates differences and tensions between European countries is the best path to uniting them.

|

The trust and solidarity among citizens that is the hallmark of the democratic nation-state does not, alas, yet exist among the citizens of Europe. |

The fact is that at Maastricht the leaders of the EU put the cart before the horse. Out of the familiar mixture of three different kinds of motive—idealistic, national, and perceived common interest—they committed themselves to what was meant to be a decisive step to uniting Europe but what now seems likely to divide even those who belong to the monetary union. At least in the short term, it will certainly divide those existing EU members who participate in the monetary union from those who do not: the so-called ins and outs.

Consequences: A House Divided

Meanwhile, one consequence of monetary union was seen even before the union happened. Such massive concentration on this single project has led to neglect of the great opportunity that arose in the eastern half of the continent when the Berlin Wall came down—an opportunity best summed up in George Bush’s phrase about making Europe “whole and free.” The Maastricht agenda of internal unification has taken the time and energy of Western European leaders away from the agenda of eastward enlargement. To be sure, there is no theoretical contradiction between the “deepening” and the “widening” of the European Union. Indeed, widening requires deepening. If the major institutions of the EU, originally designed to work for six member states, are still to function in a community of 26, then major reforms, necessarily involving a further sharing of sovereignty, are essential. But these changes are of a different kind from those required for monetary union. Although there is no theoretical contradiction, there has been a practical tension between deepening and widening.

To put it plainly: our leaders set the wrong priority after 1989. We were like people who for 40 years had lived in a large, ramshackle house divided down the middle by a concrete wall. In the western half we had rebuilt, mended the roof, knocked several rooms together, redecorated, and installed new plumbing and electric wiring, while the eastern half fell into a state of dangerous decay. Then the wall came down. What did we do? We decided that what the whole house needed most urgently was a superb, new, computer-controlled system of air-conditioning in the western half. While we prepared to install it, the eastern half of the house began to fall apart and even to catch fire. We fiddled in Maastricht while Sarajevo began to burn.

The best can so often be the enemy of the good. The rationalist, functionalist, perfectionist attempt to “make Europe” or “complete Europe” through a hard core built around a rapid monetary union could well end up achieving the opposite of the desired effect. One can all too plausibly argue that what we are likely to witness in the next five to ten years is the writing of another entry in the index of our future history books under the heading “Europe, unification of, failure of attempts at.”

Some contemporary Cassandras go further still. They suggest that we may even witness the writing of another entry under “Europe, as battlefield.” One might answer that we already have, in former Yugoslavia. Yet the suggestion that the forced march to unification through money brings the danger of violent conflict between states in the European Union does seems drastically overdrawn. For a start, there is the powerful argument that bourgeois democracies are unlikely to go to war against one another. Unlike pre-1945 Europe, we also have a generally benign extra-European hegemon in the United States. And to prophesy such conflict is to ignore the huge and real achievement of European integration to date: the unique, unprecedented framework and deeply ingrained habits of permanent institutionalized cooperation, which ensure that the conflicts of interest that exist, and will continue to exist, between the member states and nations are never resolved by force. All those endless hours and days of negotiation in Brussels between ministers from 15 European countries, who end up knowing each other almost better than they know their own families—that is the essence of this “Europe.” It is an economic community, of course, but it is also a security community—a group of states that do find it unthinkable to resolve their differences by war.

A Bridge Too Far

Now one could certainly argue that Western Europe would never have gotten this far without the utopian goal of “unity.” Only by resolutely embracing the objective of “ever-closer union” have we reached this more modest degree of permanent institutional cooperation, with important elements of legal and economic integration. Yet as a paradigm for European policy in our time, the notion of unification is fundamentally flawed. The most recent period of European history provides no indication that the immensely diverse peoples of Europe—speaking such different languages, having such disparate histories, geographies, cultures, and economies—are ready to merge peacefully and voluntarily into a single polity. It provides substantial evidence of a directly countervailing trend: toward the constitution—or reconstitution—of nation-states. If unity was not attained among a small number of West European states with strong elements of common history under the paradoxically favorable conditions of the Cold War, how can we possibly expect to attain it in the infinitely larger and more diverse Europe—the whole continent—that we have to deal with at the end of the Cold War?

“Yes,” a brilliant French friend said to me when I made this case to him, “I’m afraid you’re right. Europe will not come to pass.” “But Pierre,” I replied, “you’re in it!” Europe is already here, and not just as a continent. There is already a great achievement that has taken us far beyond de Gaulle’s Europe des patries or Harold Macmillan’s vision of a glorified free trade area. Yet to a degree that readers outside Europe will find hard to comprehend, European thinking about Europe is still deeply conditioned by these notions of project, process, and progress toward unification. (After all, no one talks hopefully of Africa or Asia “becoming itself.”) Many Europeans are convinced that, if we do not go forward toward unification, we must necessarily go backward. This view is expressed in the so-called bicycle theory of European integration: if you stop pedaling, the bicycle will fall over. Actually, as anyone who rides a bicycle knows, all you have to do is to put one foot back on the ground. And, anyway, Europe is not a bicycle.

If we Europeans convince ourselves that not advancing farther along the path to unity is tantamount to failure, we risk snatching failure from the jaws of success, for what has been achieved already in a large part of Europe is a very great success, without precedent on the European continent and without contemporary equivalent on any other continent. It is as if someone had built a fine if rather rambling palace and then convinced himself that he was an abject failure because it was not the Parthenon. Yet the case is more serious and urgent than this. For today it is precisely the forced march to unity—across the “bridge too far” of monetary union—that is threatening the very achievement it is supposed to complete.

The Case for Liberal Order

But what is the alternative? How else should we “think Europe” if not in terms of this paradigm of unification that has dominated European thinking about Europe for a half a century? How can we characterize positively what we have already built in a large part of Europe, and what it is both desirable and realistic to work toward in a wider Europe? I believe the best paradigm is that of liberal order. Historically, liberal order is an attempt to avoid both the extremes that Europe has unhappily oscillated between through most of its modern history: violent disorder, on the one hand, and hegemonic order, on the other—hegemonic order that was itself always built on the use of force and the denial of national and democratic aspirations within the constitutive empires or spheres of influence. Philosophically, such an order draws on Isaiah Berlin’s central liberal insight that people pursue different ends that cannot be reconciled but may peacefully coexist. It also draws on Judith Shklar’s “liberalism of fear,” with its deeply pessimistic view of the propensity of human beings to indulge in violence and cruelty, and the sense that what she modestly called “damage control” is the first necessity of political life. Institutionally, the European Union, NATO, the Council of Europe, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe are all building blocks of such a liberal order.

Liberal order differs from previous European orders in several vital ways. Its first commandment is the renunciation of force in the resolution of disputes between its members. Of course, this goal is an ancient one. We find it anticipated already in King George of Podebrady’s great proposal of 1464 for “the inauguration of peace through Christendom.” There we read that he and his fellow princes “shall not take up arms for the sake of any disagreements, complaints or disputes, nor shall we allow any to take up arms in our name.” But today we have well-tried institutions of bourgeois internationalism in which to practice what Churchill called “making jaw-jaw rather than war-war.”

Liberal order is, by design, nonhegemonic. To be sure, the system depends to some extent on the external hegemonic balancer, the United States—“Europe’s pacifier,” as more than one author has quipped. And, of course, Luxembourg does not carry the same weight as Germany. But the new model order that we have developed in the European Union does permit smaller states to have an influence often disproportionate to their size. A key element of this model order is the way in which it allows different alliances of European states on individual issues, rather than cementing any fixed alliances. Another is the framework of common European law. If the European Convention on Human Rights were incorporated into the treaties of the Union, as Ralf Dahrendorf has suggested, the EU would gain a much-needed element of direct responsibility for the liberties of the individual citizen.

Liberal order also differs from previous European orders in explicitly legitimating the interest of participating states in each others’ internal affairs. Building on the so-called Helsinki process, it considers human, civil, and, not least, minority rights to be a primary and legitimate subject of international concern. These rights are to be sustained by international norms, support, and, where necessary, pressure. Such a liberal order recognizes that there is a logic that leads peoples who speak the same language and share the same culture and tradition to want to govern themselves in their own states. (There is such a thing as liberal nationalism.) But it also recognizes that in many places a peaceful, neat separation into nation-states will be impossible. In such cases, it acknowledges a responsibility to help sustain what may variously be called multiethnic, multicultural, or multinational democracies, within an international framework. This is what we disastrously failed to do in Bosnia but can still try to do for Macedonia or Estonia.

Missing from this paradigm is one idea that is still very important in contemporary European visions, especially those of former great powers such as France, Britain, and Germany. This is the notion of “Europe” as a single actor on the world stage—a world power able to stand up to the United States, Russia, or China. In truth, a drive for world power is hardly more attractive because it is a joint enterprise than it was when attempted—somewhat more crudely—by individual European nations. Certainly, in a world of large trading blocks we must be able to protect our own interests. Certainly, a liberal order also means one that both gives and gets as much free trade as possible. Certainly, a degree of power projection, including the coordinated use of military power, will be needed to realize the objectives of liberal order even within the continent of Europe and in adjacent areas of interest to us, such as North Africa and the Middle East. But, beyond this, just to put our own all-European house in order would be a large enough contribution to the world.

|

European leaders set the wrong priority after 1989—they fiddled in Maastricht while Sarajevo burned. |

Some may object that I have paid too much attention to mere semantics. Why not let the community be called a “union” and the process “unification,” even if they are not that in reality? Václav Havel seems to come close to this position when he writes, “Today, Europe is attempting to give itself a historically new kind of order in a process that we refer to as unification.” And of course I do not expect the European Union to be, so to speak, dis-named. After all, the much looser world organization of states is still called the United Nations. But the issue is far from merely semantic.

To consolidate Europe’s liberal order and to spread it across the whole continent is both a more urgent and, in the light of history, a more realistic goal for Europe at the beginning of the twenty-first century than the vain pursuit of unification in a part of it. Nor, finally, is liberal order a less idealistic goal than unity. For unity is not a primary value in itself. It is but a means to a higher ends. Liberal order, by contrast, directly implies not one but two primary values: peace and freedom.