- Contemporary

- World

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- History

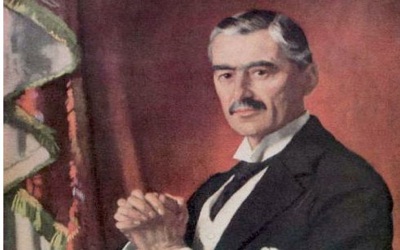

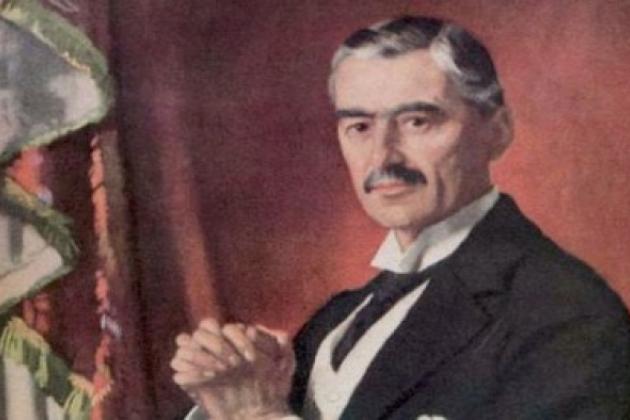

For most of us, the word "appeasement" conjures up the feckless figure of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who after his return from Munich on September 30, 1938, waved a worthless treaty and proclaimed "peace in our time" just hours after he had surrendered Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany, thus lighting the fuse of World War II. Yet it would be a mistake to think that the debacle of Munich was the fault of Chamberlain’s timidity and naïveté. A state’s temptation to appease an aggressor it is strong enough to resist has complex origins beyond the failings of any one leader.

Neville Chamberlain

A survey of three historical examples of democratic states confronted with illiberal regimes bent on aggression reveals that the roots of appeasement lie not just in the fear of conflict and violence natural to most humans. The weaknesses of democracies and the power of unexamined ideas also factor into an anatomy of appeasement. Understanding the complex answers to why a nation gives in to an aggressor may point us to more effective policies that avoid the fate of appeasers in the past.

Athens

From 359 to 338 B.C., the world’s first democracy, Athens, confronted the rising power of King Philip II of Macedonia, father of Alexander the Great. Philip’s aggressive intent was clear from the beginning of his reign, yet Athens and the other city-state powers of Greece could not form a coalition to resist the Macedonians until it was too late. As a result, the states of Greece, autonomous and free for centuries, went down in defeat at the battle of Chaeronea in 338 B.C. Greece would not be politically free again for centuries.

Two weaknesses of democracies figure into the failure of the Greeks. The glory of representative government lies in its substitution of law, office, election, and deliberation for the raw force belonging to a king or tyrant. Yet the centrality of verbal political processes means that too often procedure—words—can be substituted for military deeds. Public deliberation and speechmaking can become ends in themselves, postponing and delaying action. The great orator Demosthenes, who continually tried to rouse his fellow Athenians to more vigorous resistance, noted this flaw in Athenian politics. He criticized the Athenians as "forever debating the same question and never making any progress," and contrasted Philip’s effective "action" to Athens’ ineffective "argument."

The weakness of verbal procedure characterized interstate diplomacy as well. The ancient historian Diodorus said that Philip "prided himself more on the shrewdness of his leadership and his negotiating abilities than on his prowess in battle." In contrast to the autocratic Philip, Athenian diplomacy worked through boards of citizens who had their own factional interests, and whose decisions had to be ratified by the Assembly. As the sole authority, Philip made his own decisions and could exploit the delay that democratic procedures imposed on Athenian decision-making. Moreover, Philip manipulated the ambassadors, charming them with his personality and telling them what they wanted to hear, all while pursuing his own aims.

"Striving intemperately to ruin one another, they did not perceive, till they were oppressed by another power, that what each lost was a common loss to all."

The second weakness of democracies is their creation of what James Madison called "faction." In Athens, the short-term interests of a party or politician seeking power and influence blinded many to the threat of Philip. Indeed, some factions even cultivated Philip as an ally, or at least financer, of their own ambitions. So too with interstate relations. Old quarrels and grudges among the various city-states, such as the traditional enmity between Athens and Thebes, made it difficult to recognize the greater danger posed by Philip’s ambition. This failure to set aside parochial self-interest and unite against the aggressor was noted by the ancient historian Justin, who wrote of the Greek states, "Striving intemperately to ruin one another, they did not perceive, till they were oppressed by another power, that what each lost was a common loss to all."

England

The pursuit of shortsighted interests certainly enabled the appeasement of Germany during the twenty years between the Versailles Treaty and the outbreak of World War II in 1939. As the greatest industrial power in Europe, a thriving Germany was necessary both for trade and investment, and for the reparations England needed to pay back its own war debt. Nor was England unhappy to see Germany once again counter-balance France, England’s historical rival on the Continent.

However, many in England failed to recognize that Germany had not accepted its defeat and desired to regain its prewar dominance, and hence was a greater threat than a France devastated by the Great War. As for the failure of diplomacy, there is no greater example of the power of duplicitous negotiation than Hitler’s brilliant manipulation of Chamberlain in their three meetings. More than seventy years later it is still painful to read Chamberlain’s naïve reports of his "influence" over Hitler, who in fact considered the Prime Minister a "little worm."

For this period, however, fear and bad ideas are more significant in explaining the failure to recognize and counter Germany’s ambitions. The industrial carnage of the Great War, with its astronomical casualties and physical destruction, lay like a shadow over the European imagination in the Twenties and Thirties. The new terror of bombardment from the air convinced many in the British government and military alike that the next war would be apocalyptic in its destructiveness. Moreover, conventional wisdom stated that there was no defense against bombers, as British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin famously pronounced: "I think it is well also for the man in the street to realize that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed. Whatever people may tell him, the bomber will always get through." Such fatalistic fears made policies of appeasement seem like the height of rationality.

The obsession with the destructiveness of the next war also reinforced two bad ideas that shaped foreign policy in the interwar years. The Thirties were the heyday of pacifism, when in England there were nineteen major pacifist organizations, most of which preached that under no circumstances was war justified, and that negotiation and appeasement were the only sane way to resolve disputes. Linked to pacifism was the widespread idea that disarmament was necessary for lasting peace. As the Labour Party leader Clement Attlee said in 1935: "Our policy is not one of seeking security through rearmament, but through disarmament." Meanwhile, in a rapidly rearming Germany, "bands of sturdy Teutonic youths," as Churchill described them, were "marching through the streets and roads of Germany, with the light of desire in their eyes to suffer for their Fatherland."

It is still painful to read Chamberlain’s naïve reports of his "influence" over Hitler, who in fact considered the Prime Minister a "little worm."

Finally, idealistic internationalism abetted the pacifist delusion that force was not necessary for stopping an aggressor. The League of Nations, created after the Great War to insure that such a disaster never happened again, embodied this ideal that nations could create peace and stability through negotiation and deliberation according to transnational laws, since all peoples were progressing towards greater rationality and enjoyed a "harmony of interests," including political freedom and economic prosperity, that made war counterproductive.

Yet within a few years it became clear that nations had competing and conflicting interests, and would pursue those with violence rather than adhere to some abstract set of principles not backed up by lethal force. Japan’s brutal invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Italy’s attack on Ethiopia in 1934, and the blatant military assistance Germany and Italy gave to Franco’s forces during the Spanish Civil War in 1936-39––all involving League members attacking other League members––were met by League bluster and ineffective sanctions, destroying its credibility. By the time Germany devoured Czechoslovakia, the League of Nations was defunct, and the internationalist "harmony of interests" exposed as a wishful dream.

America

The three factors discussed above––shortsighted interest, fear, and bad ideas––have characterized America’s response to the jihadist terror threat that expanded globally with the Iranian Revolution of 1979, and its creation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the most dangerous state sponsor of terrorism. Fear obviously is the whole point of terrorism, which explicitly seeks to destroy morale and extort appeasing concessions from a more powerful enemy. America’s failure to respond to jihadist attacks, from the Marine barracks bombing in Beirut in 1983, to the U.S.S. Cole bombing in 2000, convinced Osama bin Laden that the United States had "foundations of straw" and could be frightened into changing its foreign policy with more attacks.

Political and economic interests as well have compromised a unified response to jihadist terror. Factional political self-interest and ambitions can hearten the enemy and weaken our resolve, as can the differing interests of allied nations. France’s resistance to the Iraq War in 2003 was predicated on its national interest in keeping in power Saddam Hussein, with whom France had done profitable business for decades, selling him advanced weaponry and buying his oil. These shortsighted interests obscured the greater danger of leaving in power a brutal dictator with the capacity and will to develop and use weapons of mass destruction.

The old fool’s gold of diplomacy and internationalism has likewise prevented the West from recognizing the jihadist threat and crafting proper responses. Starting with President Jimmy Carter, we have attempted to diplomatically engage the Iranian theocracy that has American blood on its hands, that has created and nurtured terrorist organizations like Hezbollah, and that is now moving toward the acquisition of nuclear weapons. Despite that failure, President Obama has met these threats with more diplomatic offers of "engagement," all of which has been rebuffed, and with non-lethal sanctions that Iran and its trading partners like China have circumvented. Once again, verbal processes and negotiation have taken the place of forceful action, giving the aggressor time to pursue his aims.

We have misread the renewal of jihadist fervor in the Muslim world.

The worst enabler of appeasement, however, has been what historian Robert Conquest called foreign policy’s greatest danger: the failure of imagination that causes us, as Conquest wrote, "to project our ideas of common sense or natural motivation onto the products of totally different cultures," and thus to "frame policies based on illusions."

Starting in 1979, we have misread the renewal of jihadist fervor in the Muslim world, attributing it to the material causes we in the secularized West prize: economic development, political freedom, or individual rights, all notions at some level inimical to the profound beliefs of many Muslims. Thus we have dismissed the careful theological justifications of jihadist violence and terror offered by Muslim Brothers founder Hassan al-Banna, jihadist theorist Sayyid Qutb, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, and al Qaeda’s Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri. We have called their pronouncements "distortions" of Islam and mere rationalizations for the material aims and needs that we value and privilege. But as Khomeini said, "We did not start a revolution to lower the price of melons."

On the contrary, the motives of jihadists are spiritual, their war one of conflicting religious creeds and beliefs: "Muslims must rise up in this struggle," Khomeini said in 1979, "which is more a struggle between all unbelievers and the Muslims." Twenty-two years later, Osama bin Laden would say the same thing after the attacks on 9/11: "This war is fundamentally religious. Under no circumstances should we forget this enmity between us and the infidels. For the enmity is based on creed."

This misreading of the motives and goals of the jihadists, then, has hamstrung our response to their violence, leading us to believe that creating democracy or developing stronger economies will trump the jihadists’ spiritual goods grounded in fourteen centuries of Islamic theology and tradition. In much the same way, many in England brushed aside Hitler’s ambitions, explicitly documented in Mein Kampf, to create a German empire based on racial purity. This failure of imagination continues to abet policies of appeasement by refusing to acknowledge that all peoples and religions are not alike and often pursue radically different aims. And history shows that these conflicting interests and aims will not be resolved by non-lethal negotiations or concessions. On the contrary, our appeasement will only hearten the aggressor, convincing him that his spiritual certainty can trump our greater economic and military power.

***

We do not face the abrupt end of our political freedom that followed the defeat of the Greek city-states at Chaeronea. Nor do we face an existential threat like the one confronting the allies in World War II. Yet we do face a slow, insidious erosion of our freedoms and way of life that will attend further terrorist attacks, particularly if the jihadists manage to obtain a weapon of mass destruction. Then we will see the wages of appeasement that follow a failure to overcome our fear, set aside our parochial, shortsighted interests, and discard the received ideological wisdom that blinds us to the true motives of the enemy.