Herbert Hoover had several careers of importance long before he became U.S. president. His exceptional ability as mining engineer, investor, and food-relief administrator is well attested to and widely known. He had a vision of a peaceful world where people could live in freedom from oppression and material want, and he understood better than any contemporary that, if that better world were going to be built, the awful past needed to be recorded. He acted on the assumption that, if history is ignored, it is bound to be repeated. He was long ahead of his time. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 he ordered his aides to pick up every stray piece of paper left at the negotiating tables or consigned to the trash can. Hoover appreciated that the history of modern times ought not to be analyzed exclusively from diplomatic exchanges, cabinet discussions, or the official maps of battles. More was required than this, and Hoover was intent on accumulating posters, photographs, and even Parisian restaurant menus. He instructed his administrative team, who were scurrying across Central and Eastern Europe on behalf of his American Relief Administration, to look out for items to add to his collection. When establishing the Hoover Institution Archives through his own initial benefaction, he saw to it that the tradition was maintained.

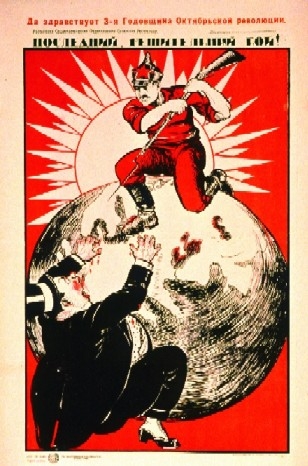

Hoover had an intense interest in communism; his philanthropic food-relief work was tied to a struggle to prevent the westward spread of communist influence from the Soviet state. Thus, the Hoover Archives constitutes the largest holding of documentary and audiovisual data on the world communist movement outside Moscow itself; in many cases what is conserved at Stanford is unavailable in the former Soviet capital.

I have been struck by many surprising discoveries in the archives while working on a history of communism around the world. It had not occurred to me, for example, that there would be much on this in the files of the American Relief Administration after World War I, but I could not have been more mistaken.

| At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 Herbert Hoover ordered his aides to pick up every stray piece of paper left at the negotiating tables or consigned to the trash can. |

Following World War I, several young U.S. officials and army officers were sent to Budapest to investigate the Hungarian political situation. One of them was Philip Marshall Brown, who arrived in April 1919. Defeated in war, Hungary had succumbed to a communist revolution led by Béla Kun. On coming to power, Kun instigated a process of communization even faster and deeper than the Communists in Russia had attempted in the October 1917 revolution. What is remarkable about Brown’s dispatches? Histories of revolutionary Hungary tend to focus on decrees, personnel appointments, and the swirl of military campaigns. Brown, though, gives us a portrait of Kun as a personality. He brings out more sharply than any subsequent writer the chaotic conditions that confronted the communist regime. Kun had recently been released from custody, and indeed he walked out of prison right into high office. The police he started to command had been beating him up only days before. Seated with him to conduct an interview, Brown noted that Kun’s head “still shows the wounds he received.”

As it happens, Brown was not the best-informed U.S. visitor, having been fooled by Kun, who misrepresented himself as a good Hungarian nationalist, not a communist fanatic. Brown thus concluded that Kun’s regime might be employed by the Western Allies as a bulwark against the spread of Bolshevism. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Kun’s policies of dictatorship, terror, and property seizures were convulsing the country. Another American saw the situation more clearly—Cap-tain T.T.C. Gregory of the American Relief Administration. Gregory wrote to Herbert Hoover in June 1919 explaining why Kun had lasted as long as he did: Romanian and Czechoslovakian forces were a constant menace to Hungary at the time, and Kun’s ferocious determination to resist occupation restricted the popular will to seek his overthrow. Kun also understood the theatrical side of politics. As Gregory reported, Kun had foreign prisoners of war marched up and down the streets of Budapest to demonstrate the prowess of his Red military contingents.

| We can never anticipate what the past will be able to tell us about the present. It is as well to conserve everything, from Trotsky’s son’s passport to the protocols of the Soviet Party Politburo. Someone, sometime may need them in the quest for historical truth. |

Yet by the time Kun was overthrown in August 1919, few Hungarians regretted it. He fled ignominiously to the Austrian frontier and eventually found exile in Moscow, where even Lenin found him unpleasantly excessive in his repressive zeal. Kun perished in the Great Terror before World War II, a victim of the same system of arbitrary injustice in the USSR that he had earlier inflicted on the Hungarian people.

Most Communists like Kun who came to live in the USSR kept quiet about the discrepancy between the Soviet ideology of a perfect future society and the realities of life under communism. But not everyone reacted this way. A group of young communist militants had proudly gone from France to Moscow in 1930. They enrolled at the Lenin School for foreign Communists and dutifully imbibed the texts of Marx, Engels, and Lenin; they also undertook training in handling guns and conducting clandestine correspondence. The idea was that the French Communist Party should acquire a cadre of able potential leaders for the political struggles ahead. The curriculum also involved some weeks of work in a Russian factory. The French delegation had come to the USSR with an assumption about the effortless superiority of Russia’s workers as a revolutionary vanguard, so the sloppiness of the Soviet labor force came as a shock. Russian workers, unlike the French workers they knew intimately, lacked conscientiousness: They turned up late and did as little work as they could get away with, and they were uninterested in outsiders suggesting ways to improve efficiency. Waldeck Rochet, a young Frenchman, said to his friend Henri Barbé: “Were we to tell the French workers what we’re seeing here, they’d throw cooked apples at us. But we’re caught in a trap and compelled to stay.”

Although Barbé seemed not too troubled by this, the typescript of his memoirs in the Hoover Archives indicates that his concerns deepened on his return to France, even though he rose high in the communist hierarchy there. He disliked the way the French Communist Party was run by Maurice Thorez. Barbé knew that Soviet agents in the Communist International supplied Thorez with political orders and desperately needed funds. After Barbé was demoted, he tried for a while to remain a loyal member of an obscure party cell at St. Ouen. But as his criticisms increased, his position became untenable. Barbé was ultimately expelled from the party in 1934. Monolithic unity had become axiomatic.

| Herbert Hoover understood better than any contemporary that if a better world were going to be built the awful past needed to be recorded. |

Just as foreign Communists in Moscow were required to turn a blind eye to many unpleasant aspects of life in the USSR, Soviet citizens who traveled abroad were obliged to adhere to strict guidelines in their conduct and discourse. The archives holds a document where these rules were spelled out in mind-numbing detail. The “Basic Rules of Conduct” were issued by the Secretariat of the Party Central Committee in 1979 on a confidential basis to all travelers. Everyone had to remember that Soviet foreign policy was peace-loving and sincere. It was essential for travelers to exhibit “high moral-political qualities” at all times and to show off a profound love for their Soviet Motherland. They were to remain vigilant against being trapped by Western intelligence agencies. If they had secret material with them from the USSR, they were not to leave it in their hotel room. It was recommended that they establish contact with foreigners solely for official purposes. They were also forbidden to receive any payment outside the terms specified for their job and forbidden to run up debts. They should always dress smartly. Even if they belonged to a tourist group, they were to act as full representatives of the Soviet state.

Of course, accidents and mistakes were bound to happen. The “Basic Rules” planned for this. Any slipup was to be instantly reported to the group leader. Contact was to be maintained with the nearest Soviet embassy or consulate. Trips around the foreign country were permissible only with the sanction of the group leader—the far-fetched idea that anyone should journey abroad unaccompanied was not even considered! Travelers were advised against taking an overnight train journey with a foreigner of the opposite sex. (Nothing, apparently, needed to be said about homosexuals because same-sex relationships were punishable under Soviet law.)

| The Hoover Archives constitutes the largest holding of documentary and audiovisual data on the world communist movement outside Moscow itself. |

With such restrictions, it is hardly surprising that Soviet citizens were extremely ill-informed about the rest of the world until Mikhail Gorbachev initiated his perestroika and glasnost reforms in the mid-1980s. “Soviet power” depended on communist rulers’ insulating their subjects from what were regarded as harmful and dangerous influences. It is not an accident that communism, wherever it has strongly established itself, has always restricted international travel, stirred up spy-mania, and jammed foreign radio stations. Where the USSR led, the People’s Republic of China and Cuba followed. And their example was picked up by North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Ethiopia. Communist leaderships in power repeatedly clamped down on the free flow of information in their countries and used propaganda to indoctrinate whole populations. Official media claimed that poverty and oppression were the universal features of life under capitalism; that capitalism was entering a period of terminal decline; and that the future, the brightest of futures, lay with communism. This was the uniform message of communist propagandists from October 1917 to the end of the twentieth century.

Consequently, when Gorbachev and his fellow reformers made their first trips to the West, they were in for a tremendous shock. Most of them had thought communism, suitably reformed, was a superior form of society to any that existed. One of the initiatives taken by the Hoover Archives after the dismantling of the USSR in 1991 was a series of extensive interviews with Soviet and American politicians who had played a part in ending the Cold War. The remarks of V. A. Aleksandrov come to mind here.

Aleksandrov was an experienced functionary of high rank who had met plenty of Americans in the course of his work. But years after he had seen President Ronald Reagan for the first time he still trembled at the impression. It was not Reagan’s words or policies that grabbed Alek-sandrov’s attention but his manners. The day in question called for an umbrella. As the president and his wife walked in the open air, the president held one aloft to shelter her from the rain. Aleksandrov recalled his own astonishment. Soviet political wives were meant to avoid the limelight; the task of sheltering them was supposed to be discharged by some nearby lackey. For Aleksandrov, Reagan’s behavior was chivalrous in the extreme—an example of an ease of social conduct that Aleksandrov was to witness on several other occasions as he became acquainted with the United States.

Aleksandrov is a splendid interviewee. He noted, for instance, that Gor-bachev’s best-seller Perestroika starts with the word “I,” which was out of step with the Soviet collectivist tradition. The individual was supposed— at least in theory—to bury his ego from view. Clearly things were changing in Soviet public life before Aleksandrov’s very eyes. A whole ideological order was slowly beginning to dissolve. The old traditions—the Lenin cult, Marxism-Leninism, and the commitment to the one-party dictatorship— were being eroded, and the politicians who were effecting these changes were themselves the beneficiaries of the Soviet communist order.

The Hoover Archives is one of the world’s great repositories of the world history of communism. It contains countless collections of official discussions, decrees, and personnel appointments on a country-by-country basis. Its archivists have remained true to Herbert Hoover’s original vision. He understood that history is to be discovered in the little details of the past. A brief sighting of Béla Kun in 1919 tells a lot about an important individual personality. A vignette of Soviet industrial practices in the late 1920s can be used to explain the fundamental problems of the USSR’s economy. The petty rules on foreign travel highlight how fearful the rulers were about their society becoming contaminated by Western ideas. And a Soviet offi-cial’s reaction to the holding of an umbrella by an American president speaks volumes about the cultural chasm that separated liberal democracies from communist states.

The lesson is obvious: We can never anticipate what the past will be able to tell us about the present. It is as well to conserve everything, from Trotsky’s son’s passport to the protocols of the Soviet Party Politburo. Someone, sometime may need them in the quest for historical truth.