- History

- Military

- US

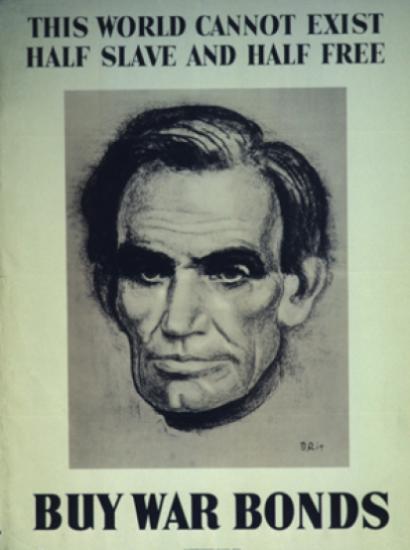

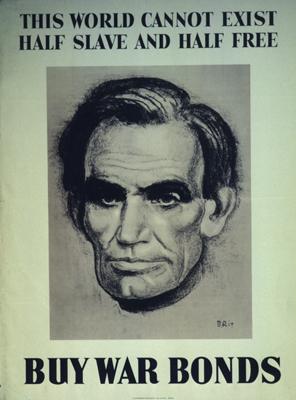

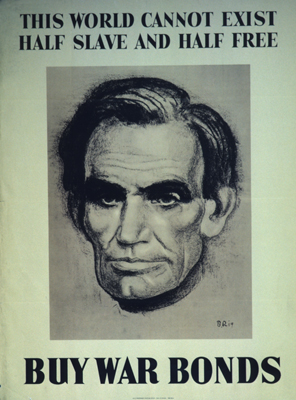

On November 5, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln replaced General George McClellan with the bellicose General Ambrose Burnside as the head of the Army of the Potomac. According to U.S. Attorney General Edward Bates, as early as September, Lincoln had been “manifestly alarmed for the safety of [Washington, D.C.],” and “wrung by the bitterest anguish—said he felt almost ready to hang himself.” Throughout the previous year, Confederate forces had inflicted a series of defeats on the Union. McClellan’s performance had been too reticent, and at the inconclusive carnage in nearby Antietam (September 17, 1862), he had reduced the Army of the Potomac’s capacity to defend the capital while increasing the Confederates’ confidence that they could take it. But the different generals into whose hands Lincoln was now placing the nation’s survival were reaping the same disastrous results. The political establishment offered no alternative. The cards were stacked against him. What is a country to do when its professionals stick to their ways, even though those ways bring defeat after defeat?

In November 2015, that is a lively question. As live images of the Islamic State’s carnage in Paris flowed to America, government officials both past and present, followed by the commentators, said that the same was likely to happen here. But all rejected as lacking professional substance the widespread popular calls to crush ISIS with straightforward U.S. military force. “We can’t kill our way out of this.” Thus our bipartisan establishment—while conceding that Islamist terrorism has grown under policies of both its “soft” Democratic side and its “harder” Republican side—asks Americans to accept the certainty of greater ravages because there are no alternatives to itself. Its perseverance in its errors stacks the cards against us.

Harsh political reality and bitter military experience taught Lincoln that his common sense was a surer guide to the nation’s safety than any general’s judgment or any faction’s reputation. The November 1862 elections punished Republicans. They had taken the nation to war, had no wholesale plan for winning it, and were losing it on the retail level. Voters do not tolerate no-win wars. Neither could Lincoln. Wanting to make sure that the Army of the Potomac’s forthcoming operation against Fredericksburg would contribute to victory, Lincoln met with the newly appointed Burnside and his superior, Major General Henry Halleck, on November 17 and proposed amending their plan for a straightforward charge up the hill. The professionals rejected his suggestions. Fredericksburg would prove to be the Union’s bloodiest, most one-sided defeat. Thereafter, Abraham Lincoln, initially reluctant to impose his logic on credentialed professionals, set about doing that, more with every passing month.

On the wholesale level, Lincoln had already edged past the mainstream Republican view of the war as simply about defending the Union. Common sense told him that preserving the Union required disposing of the problem that had threatened it since its birth—slavery. He understood that since the South was fighting for a way of life, the war would have to mean attacking that way of life, and that only a thorough military defeat could force it to yield. By degrees, he turned the Civil War into a war to end slavery. This animated the North and turned the black 40% of the Southern states’ population into allies of the Union. After Antietam, he had drafted the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves then in the possession of Confederates. In his 1862 Annual Message, he proposed a scheme for gradual emancipation with compensation. As time passed, he enrolled more black soldiers into the Union Army, to impress upon the South that resistance would entail ever-harsher consequences.

On the retail level, Lincoln increasingly insisted that military operations be part of coherent strategies. Yes, the Confederacy’s government was in nearby Richmond. But its strength flowed from the South—from Louisiana and Georgia to the Carolinas. That is why in 1863 the Union’s men and supplies flowed to that decisive theater’s generals: William Sherman and U.S. Grant. Though the Union victory in the desperate defensive Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863) was of enormous strategic significance, it resulted not from any Union strategy or generalship, but from the failure of Confederate forces to execute Robert E. Lee’s strategy. By April 1864, the conquest of the South having become unstoppable, Lincoln moved Grant north to command the destruction of Lee’s army by force majeure.

In 2015, our political establishment misunderstands the war in which we are engaged. Both its “softer” and “harder” factions conceive of the war with ISIS in particular, and terrorists in general, as a contest for allegiance of “moderate” Sunnis who, properly wooed and supported, would further marginalize the “extremists” who make up, support, flock to or imitate ISIS. But the distinction between “moderate” and “extremist” is purely American, and does not explain the war. ISIS-type horror was common in intra-Muslim strife for centuries during which, however, the Muslim world was in awe of the West and left it alone. Only in recent decades, as significant numbers of Muslims lost respect for Western peoples, as they have indulged their fantasies with near impunity, have they turned their grisly, immoderate ways against us. In fact, the only way to stop this assault upon us is to re-establish respect. The “softer” wing’s recipe to woo the “moderates” mostly without stationing many U.S. ground troops in Muslim nations, as well as the “harder” wing’s willingness to use U.S. “boots on the ground” to help sort “moderates” from “extremists” are counterproductive in this regard. Americans demand safety from terrorists. Statesmen attentive to Lincoln’s experience in 1862 would answer these demands by setting aside this self-generated fog, being clear about what moves our enemies, and by focusing our military physically to eliminate them.

Properly understanding the war means taking into account the fact that the Sunni peoples over whom the Islamic State rules welcome ISIS because, in the context of the great Sunni-Shia war of our time, ISIS is an absolutely reliable shield against their Shia enemies. The discomfort that ISIS’ rule has brought its hosts looms small against this great benefit. ISIS’ Sunni hosts will not part from them unless and until Western attacks on the cutthroats cause so much collateral damage that the cost of staying loyal to the “extreme” Sunni cause becomes prohibitive. By the same token, hoping that the Muslim world’s Sunni powers will join to crush ISIS and stop inciting anti-Western terrorism will continue to be in vain because the ideology of ISIS is but a more explicit form of the Wahhabism that is the official religion in Saudi Arabia and much of the Gulf. Were these states to wage war against “Sunni extremism,” they would be gambling their lives. Only extreme U.S. pressure might lead them to do it. These realities dictate that, for the West, and for America in particular, straightforward military logic is the key to our peace.

That would mean using air power to isolate ISIS-held areas from the wherewithal of life and war—food, fuel, people, and all manner of supplies. As shortages weaken ISIS fighters, those civilians who seek to leave should be screened. Then, bombardment by air and artillery should reduce ISIS-held areas to rubble ahead of armored units. The point would not be to take prisoners, but that such as might escape be left to the mercies of their local enemies. Destroying ISIS physically would remove the major current source of terrorism and of encouragement thereto. It would also strike a major blow at the disrespect that is fundamental to the phenomenon.

In November 1862, the cards were stacked against the Union. Little by little, Lincoln re-stacked them by his logic. According to America’s bi-partisan establishment in November 2012 (indeed as per the Department of Homeland Security’s charter), Islamic radicalism and its attendant terrorism are permanent features of modernity. The cards are stacked against any attempt to rid ourselves of them. Today as ever, the statesman’s job is to re-stack them.