- US Labor Market

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Energy & Environment

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

“Nobody knows anything.”

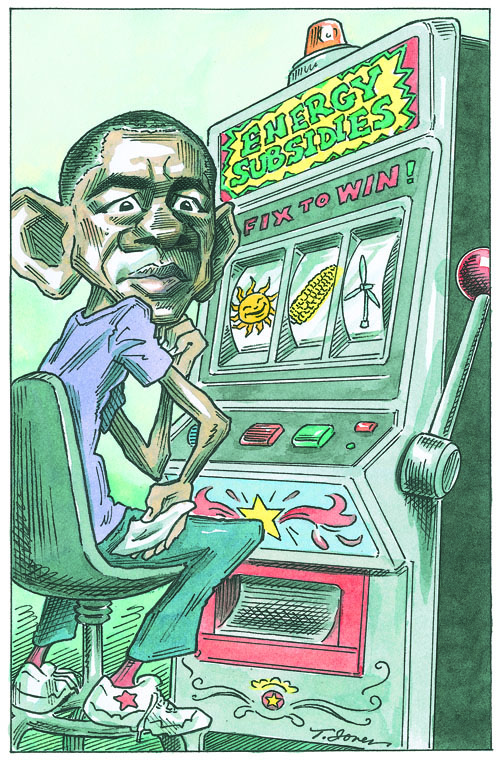

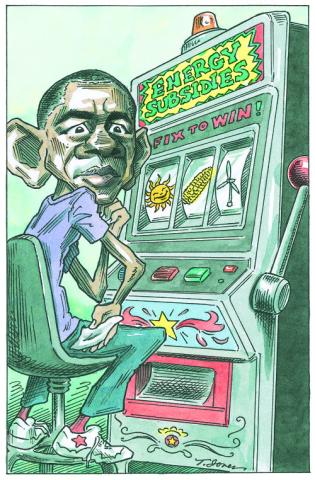

William Goldman, a legendary screenwriter, made this observation about predicting the box-office success of movies before they open, but his comment could just as easily be about projecting the success of specific renewable-energy technologies before they are widely deployed. And that is why subsidizing the deployment of individual renewable-energy technologies—picking winners, in other words—is a bad idea, both for fiscal responsibility and for the long-term health of the clean-technology economy itself.

This does not mean that governments should do nothing. The support for basic scientific research and even applied R&D is one of the few governmental expenditures that actually produce a good societal return on investment. Funding a broad and sustained clean-tech R&D effort by government, academia, and even, subject to tight restrictions, within industry, makes a lot of sense.

But loan guarantees to private firms, whether those are Solyndra (bankrupt), Beacon Power (bankrupt), or Fisker Automotive (for a 20 mpg hybrid sports car), are a bad idea. The Obama administration has tried to combine an energy policy, a stimulus policy, and a jobs policy all in one, with the net result being both policy incoherence and charges of corruption, incompetence, and conflict of interest. As Larry Summers, then–Treasury secretary, wrote at the time of the Solyndra investment in an internal e-mail: “Government makes a crappy VC.”

Far better is a system that levels the playing field by removing all direct subsidies for energy production, whether they be for fossil fuels or renewables. And putting a moderate price on carbon, preferably through a revenue-neutral carbon tax, could further allow renewables and conventional fossil fuels to compete on an equal footing. This is not because we should unthinkingly subscribe to some of the more doom-and-gloom projections about carbon put forth by many environmentalists. Anyone who understands anything about the history of energy modeling in particular or predictive modeling in general understands that projected damage estimates from climate change are not far removed from pure guesswork. Rather, a moderate carbon price can be justified as an insurance policy against the sort of bad outcome that has a reasonable chance of occurring.

While pricing carbon can help boost renewable technologies in general, the idea of picking particular winning renewable technologies is a fool’s errand. Many environmentalists have been calling for heavy subsidization and massive build-out of renewables almost since the first significant wind turbines and solar panels were introduced in the 1970s. If we had been foolish enough to listen to them and subsidize these early-stage technologies on a mass scale, we would have an energy system even more expensive, unreliable, and dysfunctional than what we have now—with probably little impact on the climate to boot. Instead, through three decades of R&D improvements we have at least brought these technologies to the level where they can compete with fossil fuels in certain situations. And nobody knows where the next breakthrough will come from. Until the natural-gas fracking revolution was unleashed a few short years ago, almost every expert in academia and industry thought we were running out of natural gas. Now we are figuring out what to do with our abundance.

This highlights another problem with subsidies. Heavy subsidization of sort-of-OK renewable-energy technologies tends to crowd out funding of R&D on the true breakthrough technologies we would need to transform our energy system. Subsidies also cause complacency and weaken the relentless focus that companies need to get renewables to be competitive at the “Chindia price”—a price they will need to hit if they are to be widely deployed globally rather than simply in politically favorable regimes in California or Europe.

All this is not to imply that renewables advocates should “unilaterally disarm” while mature fossil-fuel technologies still enjoy substantial subsidies and underpriced pollution penalties. While production subsidies and loan guarantees are fraught with both substantive problems and political peril for the renewables industry, public policy is an imperfect place, and within that imperfection there are far stupider things that the government does than giving renewables some sort of a nudge. But if we want a sustained boom in renewable energy that can actually make it an important part of our energy landscape, we need to concentrate on funding the R&D that will allow us to make fundamental breakthroughs—not on tinkering around the edges by subsidizing the politically favored renewable flavor of the week.