- History

- Military

Over the past several decades, as historians have unraveled the archives of the Red Army after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the new narrative of the history of the Second World War that has emerged has emphasized the fighting on the Eastern Front as the crucial theater of the war in Europe. Certainly, the casualties that the Soviet peoples endured were far beyond the losses the Western Allies suffered, while the fighting on the Eastern Front contributed substantially to breaking German ground forces. Yet, an overemphasis on Soviet casualties, no matter how impressive, fundamentally distorts the extent of the effort that the Western Powers waged against the Third Reich.

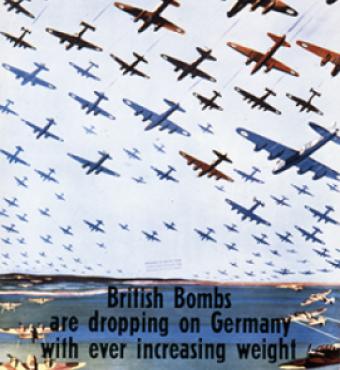

Largely because of the Wehrmacht’s success in destroying the French Army in May 1940, the Western Allies were incapable of mounting the forces required to make a successful amphibious landing on the French coast before spring 1944. It is worth noting that while the Germans were destroying the French, the Germans needed to keep only a few divisions in the east. With the collapse of the Western Front, the only alternative to an impossible “second front” was a strategic bombing offensive, which fit into the industrial and societal nature of Western society. Unfortunately, the first three years of the RAF’s bombing offensive represented a dismal failure. However, in spring 1943 matters turned with the addition of new bombers, tactics, and technological aids. In the Battle of the Ruhr, the RAF’s Bomber Command savaged Germany’s main industrial area. As Professor Adam Tooze has noted in his masterful history of the German war economy, that effort suppressed the rapid upward swing in German war production significantly. The numbers provided by the Wehrmacht’s economic inspectorate for the Ruhr underline Tooze’s conclusion. The decline in coal production was 873,278 tons over the three-month period in spring 1943. The result was also a shortfall in steel production of 400,000 tons with accompanying shortages in parts, castings, and forgings.

The larger picture over the following two years is even more impressive in terms of the contribution of what was termed the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO). By summer 1943, the American Eighth Air Force had entered into the lists. Unlike the British, it attempted to mount its bombing offensive by raiding German industry during the day. While it suffered heavy losses, it also inflicted heavy casualties on the Luftwaffe’s fighter forces. It was also able to do significant damage on the German ball bearing and aircraft industries. By 1944, the American daylight effort finally found its raids supported by long-range escort fighters, which both the RAF and the US Army Air Corps had denied were necessary before the war. The P-51 Mustang provided both support for the bombers and a means to break the Luftwaffe and win air superiority over the whole of the European continent.

Numbers underline the contribution that the CBO made to the victory over the Germans. By early 1944, the Germans found themselves forced to devote 13,500 heavy anti-aircraft guns (88mm, 105mm, and 120mm high velocity artillery tubes) and 32,000 light artillery flak pieces, supported by 1,365,000 soldiers and civilians, to the air defense of Western Europe. Without the Combined Bomber Offensive, it does not take a rocket scientist to figure out that an additional half-a-million soldiers and 10,000 high velocity guns on the Eastern Front might have had a disastrous impact on the Red Army’s ability to fight the war in the east. One recent study of the war estimates that the construction of air frames, air engines, and weapons for aircraft consumed at least 50 percent of German productive capacity. When one adds the anti-aircraft effort and the war at sea the Germans committed at least 60 percent and probably considerably more of their productive effort to the war against the British and Americans.

Finally, we might note that while the casualties suffered by the Western Powers in no fashion equaled those of the Red Army, the losses of picked men of high intelligence in the air war were extraordinarily high. From April 1943 through to April 1944, crew losses among American B-17 squadrons in Eighth Air Force attacking German industrial sites averaged close to 30 percent every month. The casualties suffered by the RAF’s Bomber Command were 50 percent killed of those who flew on active operations, while barely 25 percent survived the war unscathed. In the end, it took a combination of both the air war with its bombing of the Third Reich and the war in the east to break the military and economic power of the most evil regime in human history. Both were essential parts of a terrible war of attrition.