- Science & Technology

- Education

- History

- Higher Education

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

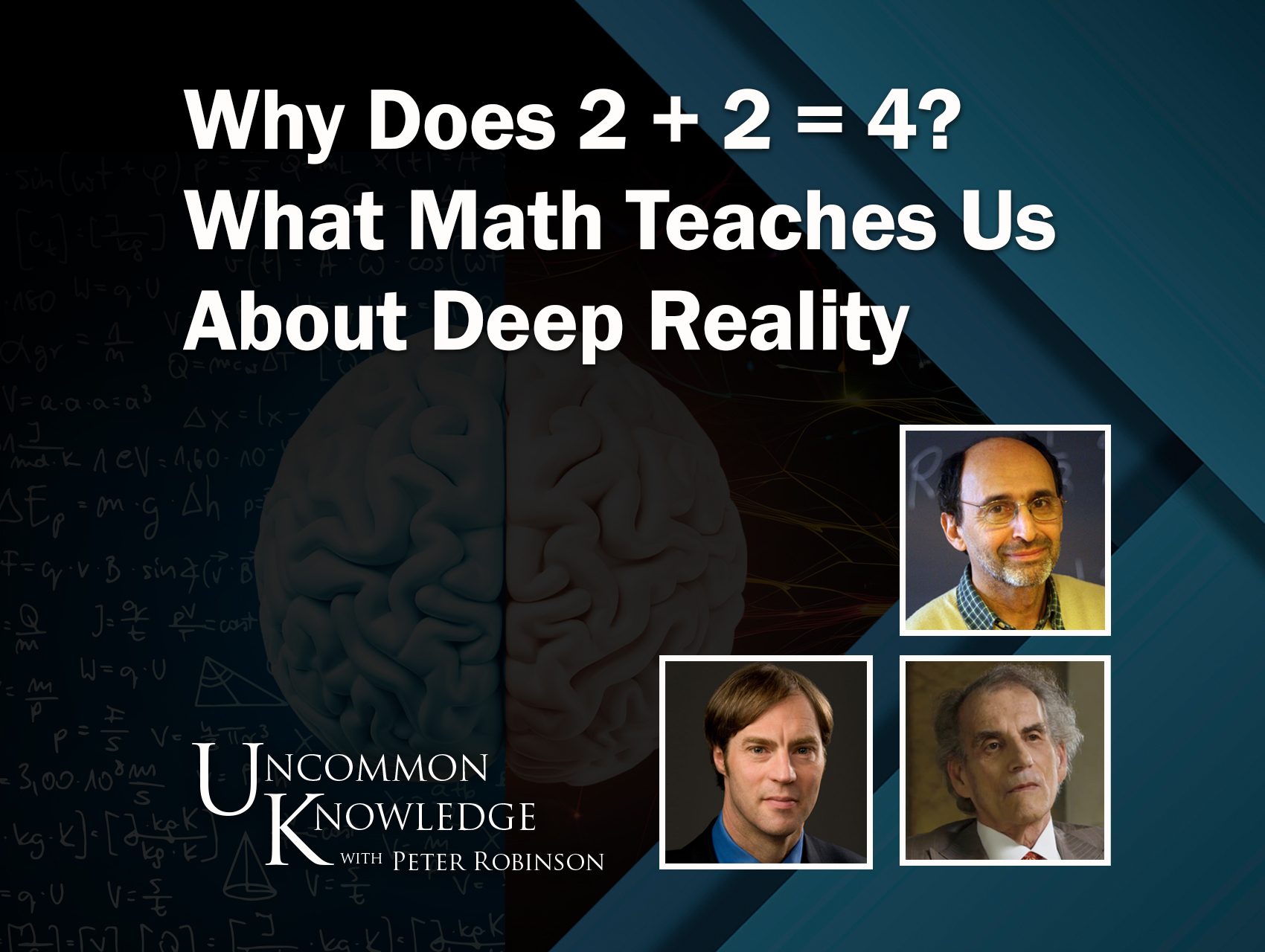

In this episode of Uncommon Knowledge, Peter Robinson sits down with mathematicians David Berlinski, Sergiu Klainerman, and Stephen Meyer to explore one of the deepest mysteries in science and philosophy: the reality of mathematics.

From the simple certainty that 2 + 2 = 4 to the mind-bending mathematics behind black holes and quantum physics, the conversation asks why abstract numbers—created in the human mind—map so perfectly onto the physical world. Is mathematics purely logical, or does it point to a deeper structure of reality that isn’t material at all? Along the way, the panel explores beauty in science, the “unreasonable effectiveness” of math, and whether the concept of materialism can really explain the world we live in.

This wide-ranging discussion blends mathematics, physics, philosophy, and metaphysics into a fascinating conversation about truth, beauty, and the nature of reality itself.

Recorded on October 24, 2025.

- 2 + 2 = 4. In all places, and for all time, 2 + 2 = 4, but why? What does math tell us about the nature of reality? David Berlinski, Sergiu Klainerman and Stephen Meyer on "Uncommon Knowledge" now. Welcome to "Uncommon Knowledge," recording today in Salzburg, Austria. I'm Peter Robinson. David Berlinski has taught math, philosophy and English at universities, including Stanford, Rutgers, the City University of New York and the Universidad del Peru. I hope you like that pronunciation, David.

- Perfect.

- He is the author of books including "One, Two, Three: Absolutely Elementary Mathematics." And his forthcoming volume, "The Perpetual Rose." A native of Romania, Sergiu Klainerman is a professor of mathematics at Princeton. In his own words, his current interests include, "The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes," more precisely, the rigidity and stability. I'm reading these words without having any idea what they mean. "And the dynamic formation of trapped surfaces and singularities." I'll ask you to explain a little bit of that maybe, Sergiu. The director of the Discoveries Institute Center for Science and Culture, Stephen Meyer started his professional life as a geophysicist. He returned to school, earning a doctorate from Cambridge in the history and philosophy of science, he has established himself as one of America's leading thinkers in intelligent design. His most recent book, the "Return of the God Hypothesis." David, Sergiu, Steve, welcome. In the "Return of the God Hypothesis," Steve's latest book, he argues that three relatively recent developments suggests that science needs to return to some notion of the transcendent. And these three developments are the Big Bang, the fine-tuning of the universe and the discovery of DNA. After reading Steve's book, a certain very accomplished, well-known mathematician, took Steve aside and said, "You only named three developments that suggest a transcendent mind. There's a fourth." Sergiu, what did you mean by that?

- Well, first, I should say, Steve talked about developments and mathematics is forever, I mean, has been around for thousands of years, so it's not quite fair to compare. But mathematics, by definition, deals with its own reality, which is, I claim as objective as the physical reality. So, for example, black holes are like that, right? A black hole by definition, we have a mathematical theory of general activity that predicts black holes, but by definition, a black hole cannot be seen. So nevertheless, we can assert its existence, why? Because general relativity is a consistent theory.

- So black holes scare the daylights out of me. We'll come back to black holes, I'm sure, but my mind already hurts is just when hearing about your work on the rigidity, all right. In layman's terms, which is to say for me, 2 + 2 = 4, is real.

- Correct.

- That's not a figment, it's not an artifact of our mind of mental processes, of the accidental processes that might be going on in our neurons.

- Correct.

- Whether I think it's 2 + 2 = 3 or 5, I'm wrong. 2 + 2 does equal 4, and that is objectively real.

- Correct, right.

- Therefore, there is a conceptual objective reality that exists outside us.

- Right.

- It's not material.

- It's not material. And this is actually a big deal. David shrugs.

- Yeah, of course, it's a big deal, I mean, 2 + 2 = 4, is an interesting example. But you can derive that biological inference from still more fundamental ideas, which is an exciting and interesting fact on its own. You don't have to begin by affirming 2 + 2 = 4, there I stand, I can do no other, you can say, I have derived that from still more primitive conceptual items. But when you go back and back and back and back and you ask about the initial assumptions, the axioms of the system about arithmetic, there is no additional defense that you can offer beyond the consistency of the whole, which is a very interesting position to find oneself.

- So I'm going to quote to you from your book.

- Nothing better.

- "One, Two, Three." I think this is, I'm hoping this is the same point because that will indicate that I have actually understood you, quote, "Neither the numbers nor the operations they make possible permit an analysis in which they disappear in favor of something more fundamental. It is the numbers that are fundamental. They may be better understood, they may be better described, but they cannot be bettered."

- I still think that's true. Bear in mind when you say, 2 + 2 = 4, that's an assertion.

- [Peter] Yes.

- What I'm arguing for in that particular passage is that when you go back to the foundations of arithmetic in the expectation or the hope that you can get rid of the numbers, you are going to be very disappointed because they reappear.

- All right. I'm going to quote David once again, but I put this to the two of you for judgment. I'm assuming he will agree with himself, although in David's case, this is always a question. Again from his book, "One, Two, Three." Quote, "Across the vast range of arguments offered, assessed, embraced, deferred, delayed, or defeated, it is only within mathematics that arguments achieve the power to compel allegiance. No philosophical theory has ever shown why this should be so. It is a part of the mystery of mathematics." So you argue from some philosophical point that derives some Aristotle and has seemed straight, but I can still say, "You know I'm not persuaded," but when you say to me, 2 + 2 = 4, of course you're right about that. Is that the point?

- I can speak to this from the standpoint of someone who's worked in the natural sciences and as a philosopher of science, the natural sciences provide empirical or observational evidence in support of conclusions. And scientists will evaluate particular theories or hypotheses by comparing your explanatory power or their predictive power. But the logical form of those arguments does not render a deductively certain conclusion. You, in the best of cases, will make an inference to a hypothesis which provides the best explanation.

- Hang on one second, right? Just distinguish deduction from an inference for us.

- Right. So a deductive argument will start with a major premise. All men are mortal, a minor premise, some fact about the world.

- Socrates is a man.

- Socrates is a man, and then a conclusion, therefore, Socrates is immortal.

- Socrates is immortal. Right.

- Okay. And if the premises are true and the reasoning is valid, then the conclusion can be affirmed with certainty. But in the natural sciences, you start with facts that you've observed about the world and you want to infer from those facts to either some kind of generalization, that would be an inductive argument or to some sort of causal process that might explain what you're seeing around you. Those arguments typically characterize as abductive, the kind of detective reasoning that we enjoy when we watch detective shows.

- Colombo.

- Yeah, Colombo or someone's trying to figure out who had done it. And so those abductive and inductive inferences, when you examine the logical forms, turn out not to give you certainty. They may give you plausibility, they may give you comparative plausibility where one theory is very much better than another, but they don't give you the kind of certainty that mathematics alone and mathematical logic can give you.

- And this is why a good scientist will never say any more than the theory is X, Y, Z, and on the best evidence it holds up for now. Whereas, a mathematician feels perfectly confident in saying, I've proven, we've proven it.

- It's true for all time.

- [Peter] We have a proof, correct?

- When we say proof in science, the mathematicians, however, are better than we are.

- [Peter] When you say you've proved something, you mean it?

- Yes.

- All right, okay. So this, go ahead.

- It could be wrong, but somebody will show it to me that it's all right.

- Yeah. So if this brings us to Sergiu's article, an inference, a magazine that you edit, David, the articles entitled, "Reflections on an Essay by Wigner." Now, Eugene Wigner, I have to set this up, was a 20th century mathematician and physicist. In 1960, he wrote a famous essay, "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences." Wigner noted his surprise that mathematics, which after all goes on in our minds, should prove so useful in describing and even predicting aspects of the physical world. Okay, can you give me a couple of examples of this? I mean, when I think to myself, wait a minute, so I have a dream in the middle of the night, I wake up and it turns out it was untrue, but if I do a mathematical equation and I wake up, it's still true.

- Well, Sergiu wrote a brilliant essay, and what he showed was that you can start with very simple mathematics and build up to more and more and more complex forms of math, essentially deductively. And then those complex forms of math, take the calculus, take differential equations, they map beautifully onto the physical world to describe actual processes that are taking place in nature so that they provide very precise descriptions of things that are going on in nature. And what Wigner is alluding to is the mystery that this or the puzzle that induces for a lot of physicists, why should the math that we have developed through a series of deductive steps effectively from our own reasoning map so beautifully to processes that we sometimes haven't even observed yet. And David has a number of great examples in "One, Two, Three," of mathematical structures that were developed well before they had any application to physics, but then later were crucial and maybe, he should speak to that.

- Yes. I mean, Eugene Wigner raised a very interesting point and people have been discussing it. If you look at theoretical physics, the great structures, Newtonian mechanics, general relativity, quantum mechanics, you can't do it without a lot of mathematics. You just need a whole lot of mathematics. And Wigner raised the question, is, you know we need mathematics to do quantum mechanics, but we don't need entomology. How come the bugs don't figure in quantum mechanics, but the numbers and the complex numbers do? And that is a rewarding and a provocative question, but we don't have to turn to quantum mechanics. There is a glass here, there is a glass here, one glass, one glass. How many glasses are in front of you? Two. From where do you derive that assurance that there are two glasses in front of you? It's not a physical observation because nothing in the physics of the situation reveals the fact that one and one are two, that is something someone would think that's additional. Now, we can break that all down into smaller steps. And that's what logicians have done in the 20th century. They've shown us that the method of proof can be decomposed into very small steps, in fact, so small, a computer can execute them. And the initial assumptions can be made so general, in fact, so general that they encompass all of mathematics as in set theory or category theory for that matter. But we are in all this, in rather an awkward position. I happen to be looking out at a beautiful alpine lake now, and just imagine, we see somebody on the other shore who begins walking across the water without any assistance whatsoever. He's just crossing, walking one step in front of the other and he's crossing the lake toward us, and he comes, completely dry, he appears in front of the television camera and we say, "How did you do that?" And he says, "Well, I took very small steps, I took very small steps." Now, our natural reaction would be, that's commendable and you got across, but somehow or other, it's not the answer to the question. And we are all in the position of watching someone cross a large body of water and explaining his success by saying, "Look at my feet, small steps." That's where we are.

- Okay, so Sergiu, well, wait, lemme go back to your essay. I'm quoting you once again, "The mystery Wigner points out arises in part from the perennial question of whether mathematics is a science, advanced by exploration and discovery like the main physical theories or whether it is an invention, a creation of the human mind. I argue that mathematics developed through exploration and discovery." That is to say, it is like a nugget in the ground, you find it.

- Correct.

- [Peter] Okay.

- Yeah, no, absolutely, I mean, one image that you could make is that of an alpinist that is trying to go on the top of the mountain. He has an idea.

- Everybody's doing alpine metaphors today.

- Yeah. He has an idea where he wants to go, right? So that's very important. That's part of doing mathematics. It's not just deduction.

- Right, right.

- It's sort of a vision of where you want to go, which is very important.

- [Stephen] Inspiration, yeah.

- Right, has something to do with inspiration. But then, you know, you have something very objective in front of you, right? The stone is of the Alpines that you have to take into account that you are not going to fall, you have to touch the stone to know exactly where you are going. And if you don't, you get into trouble. So mathematics is very similar. People have the feeling that everything is deductive, it's not, I mean, it is very similar in that respect to physical sciences. Physical sciences also, you have, let's say, an expectation, you make a hypothesis.

- Right.

- Right. The choice of a hypothesis is not a deductive thing, it's an insight. And then you try to show that it fits everything else, all the other experiences. So-

- And that's the process of proving something, right?

- [Sergiu] Correct.

- So you have the processes.

- Right, exactly.

- [Stephen] Once you have the process of discovery, but then the process of justification.

- The process of justification. So mathematics, at the end of the day, it looks like a chain of logical sequences that the computer can also, I mean, once you have the chain, the computer can go very fast to it and maybe even check. So there are yet no computers that can check launch. I mean, they can check small proofs, but not large ones. In any case, it's sort of a very good example, I think that illustrates very well relations between maths and physics. Take geometry, so geometry was the first really theory of the physical world, right? I mean, it's what it describes what we see.

- We going all the way back to Euclid, is that what you saying?

- Right, so Euclid, obviously, tried to make sort of mathematical statements out of. But it's a physical theory without doubt, including, geometry is a physical theory. Then it develops. So here, comes up something specific to mathematics, different from physics. Mathematicians can take a theory and then develop based on very different criteria than a physicist would do. So, you know, they're interesting in problems because they're beautiful or because they feel that it will lead to a certain understanding of something else. And this freedom really, in the case of geometry went for, I dunno, 2,000 years without essentially no connection back to the physical world. I mean, Korean geometry was there to start with, but then, by the 19th century, you have, you know, have Gauss, you have Lobachevskian, you have Gauss, you have Riemannian, you have Minkowski at the beginning of the 20th century. And then all of a sudden, all that stuff becomes an essential ingredient. I mean, you know, it's not just the technical, it's an essential ingredient of special and general activity, right?

- Comes directly applicable to fundamental physical theory.

- And I think this has happened many, many, many times, and maybe, it's not very well acknowledged.

- So can I ask, when you, Sergiu, needless to say, I cannot evaluate your work on my own because you have done a 2,000 page proof, 2,000 pages of close mathematical reasoning. I could live to 2,000, I could read a page a day or a page a year, and it still would escape me, I'm sure. And this was on the stability of some aspect of Albert Einstein. So may I ask, did you think you were doing a work of art, creating something beautiful? Or did you think you were interrogating reality? I'm trying to understand.

- Okay, okay.

- [Peter] What it felt like to you as a working mathematician.

- Great question.

- It's a very deep question.

- [Peter] Deep, deep, very difficult problem.

- And the answer is both. I mean, I would take the problem in the first place, I'm a mathematician, I'm not a physicist, right? I believe that the best mathematics is connected somehow with physics in complicated ways. But there are many problems in physics, and I will pick the one that satisfies my aesthetical feeling as a mathematician. So that's a say, hotspot.

- Your aesthetic feeling. So explain that, you want something that's good-

- Something that I feel is very beautiful, it's very profound. It gives lots of very interesting questions. Okay, so that's one aspect. But then it has to be the second, for me at least, there has to be a second aspect, which is that it should say something about the physical world. And in this case, it does, right? I mean, the Kerr solution. So here how it goes, right? You have general activity, which was well-formulated by Einstein at the end of 2015, 1915, excuse me.

- And this was at the time, a new theory of gravity.

- [Peter] Yeah.

- Massive bodies curve, what's called, space time.

- And then certain solutions were found, Schwarzschild was the first found in 2016, immediately a year after found a so-called, Schwarzschild solution, which is a stationary solution with a lot of symmetries that you can actually extract from the serial relativity, from the answer equations as exact formula. And that had led to lots of issues because it has a singularity. This is connected later on with the Penrose Singularity Theorem, for which he actually got a Nobel prize. He's the only mathematician to have gotten a Nobel Prize in physics, there's nobody else.

- Because the math applied so beautifully-

- Right, or to a question that was a very important question.

- Yeah.

- It was very good. And then there was a second major development by Kerr. This was 1963 where the Kerr solution was. Okay, so now you have a Kerr family, which includes, Schwarzschild, it's a large family depending on two parameters. So these are exact solutions of the equations, right? From a mathematical point of view, they are real because for me, mathematical reality has to do with objective fact that these are solutions of an equation, which you can write down, it's conceptually.

- And may I interrupt for just a moment. So if I understand one of the remarkable things about Einstein, by the way, of course, correct me, jump in, I'm doing baby talk here because that is the top of my form when it comes to this material. Einstein comes up with general relativity in 1915, and here we are in 2025, there have been experiments that have been done over the course of the succeeding century as new satellite, new technology, new experiments.

- Yes.

- And every single time, the theory of general relativity is proven out.

- Right, yes.

- That is to say, this theory that Einstein came up with on a chalkboard for a century of experiments now, it turns out to correspond with and predict reality and your work, if we could somehow devise experiments on black holes, your work would prove out. It's real to that extent.

- So I like to call it a test of reality. So the fact that the Kerr solution is stable, right? It's a mathematical statement, but with a lot of physical content because let's say, if it was not stable. So it's a solution, a correct solution of the equation, which starts with specific initial conditions, right? So the issue of stability is now, we make small perturbations of the initial conditions, and all of a sudden, we get something entirely different, which has nothing to do with the solution, the Kerr solution that would be called, instability, right? So if the Kerr solution would be unstable, it means, it doesn't have any physical meaning, right? Because you know, it doesn't correspond to anything that you can recognize in nature that's corresponding to that, right? So the issue of stability is a fundamental issue in-

- [Peter] It's a market for reality.

- I call it, mathematical test of reality.

- What's going on here, Peter? It's so interesting.

- Explicate for us.

- Well, from a philosophical point of view here, is that there's a deep assumption that that which is mathematically consistent, coherent, stable, is going to give us a guide to physical reality as if there's a rationality built into the physics that somehow matches the rationality that's at work when we're doing this type of advanced mathematics. And so that's the Wigner mystery. Why does the reason within match the rationality of nature external to us, the reason without.

- All right, so now, now we move into territory. I'm already in over my head, but I continue swimming, it gets deeper.

- May I offer a simple thing that might help because we got the field equations of general relativity and the solutions, but Sergiu started initially talking about geometry.

- Yes.

- And just the idea that mathematical objects have stable properties. This is why mathematicians regard them as real, you know, circle has certain basic properties. So it's got a circumference area and we can calculate these things. And those properties are true for all people who think about circles. There are stable properties that that geometric object has that we can describe mathematically that's independent of our minds.

- Right.

- And yet, the stability of those properties is a token as Sergiu has explained in our recent conference, it's a token of reality, a mind independent objective reality. And that's why mathematicians don't think that they're inventing new mathematical formulas. They almost universally feel that they're discovering something, not inventing.

- Well, there are some who don't, but what's interesting is that physicists always refer to mathematics as being an invention of the human mind. That's what Wigner says.

- Yeah, yeah.

- Sorry, Einstein says an invention of the human mind, but Wigner says something very similar. So I'm always surprised to see that...

- Einstein felt he invented the general.

- No, no, no, Einstein feels that mathematicians invent things, right?

- He actually called it, a free creation of the human mind.

- [Sergiu] Right.

- So free, which he meant what?

- It's not really clear because if it's a free creation of the human mind, why are mathematical propositions so dreadfully necessary? I didn't have much choice about 2 + 2 = 4, and I presume you didn't either.

- But there's a, apologies.

- Kind of at odds with the notion of spontaneous, spontaneously reaching an invention like addition doesn't seem to be an invention at all.

- But I have a reason why physicists do that and I doubt that Newton would have said that.

- [David] No.

- It's a modern physicists who are materialists, they do believe that there is just matter and everything the mind including has to be determined somehow by that.

- But they can't be right. So okay.

- Notice what's in the dialectic here, the mathematicians who are doing the math, that are developing the math typically believe that they are discovering something that is real and independent of their mind. Not inventing something like an internal combustion engine.

- Exactly. I mean, any invention has to have a starting point, right? So it means that before that starting point, that mathematical fact did not exist, right? Pythagorean theorem was not true before Pythagoras discovered it. It's kind of ridiculous.

- But how can anybody, there must be complexities here. I'm sure there are complexities, I'm not grasping, but 2 + 2 = 4, is true for me, it's true for you, it's true for David, no matter how perverse David may be feeling at any given moment, it's still true and has been true for all time. Therefore, there is something, doesn't that just put a stake in the heart of materialism right there? Something exists outside us. Something, we can call it reason, we could call it platon. Okay, so let's go to Plato. If I understand this much, in the republic, Plato draws a distinction between the intelligible world, the sensible world is what we can see and touch. And the intelligible world is intelligible to us, but-

- Access to the mind, yeah.

- Access through the intellect. Okay, and so that's where he places his ideal forms. There is a circle out there, there is a triangle out there. Plato says, it does have an independent existence, but he seems to suggest that there's a realm of ideal forms someplace out there. Aquinas comes along 1,500 years later and says, ideas exist in minds and something that is true for all of us and for all time, that is intelligible, but immaterial exists in the mind of God. David?

- Yeah, maybe.

- David was never more David than in that very moment.

- I can't make any sense of the discussion so far, that's my problem. There is a problem to which Wigner was calling attention, which is a real philosophical problem. That is, if mathematics is essential for every physical theory, it cannot be the case unless it's a trivial explanation that there is a physical theory that physically explains mathematics. I mean, if a man proposes to catch a carp by baiting his hook with a carp, he's engaged in a trivial pursuit. He has the carp. If we need a physical theory that includes mathematics, to explain mathematics, we no longer have a physical theory. We have a physical and a mathematical theory. And that's the dilemma. I think the deep dilemma to which Wigner is calling attention. There are certain principles we'd like to hold onto, it's part of the cultural imperative. We'd like to hold onto this fundamental idea, the world is physical. We live in a physical world. I'm not saying this is a commendable idea. I'm saying, it's a cultural imperative because it seems so reassuring. Look, we're faced with imponderables, the basic fact, the thing is a material or a physical object, it is very inconvenient culturally and intellectually to come to the conclusion that in order to understand that physical object, we need a whole lot of non-physical facts about mathematics. And in order to explain a whole lot of non-physical facts about mathematics, there is no conception of a physical theory without mathematics that can do the explaining. So we're left in the position that if mathematics is as useful as Sergiu and Steve says, and they're absolutely right about that, it's useful in daily life. There is something fundamentally wrong with our idea of the world as a physical cystic.

- Exactly.

- Something cannot be right. Something has to give. Either we develop physical theories with no mathematics, Feynman conjecture, something of this sort. Or we agree that materialism simply cannot be right, one of the two, but something has to go.

- But physics will until now at least have not given up on the idea of physicality.

- [David] No.

- So that's a issue.

- But they're not reckoning with the dilemma that David just described, I think.

- No, not me. I mean, that dilemma has been in the literature for at least, 50 years or 60, I mean, even a hundred years.

- I don't understand all of you bright people, if something's been in the literature for half a century, which essentially is a stop sign, saying, wait a moment, wait a moment, wait a moment. You have a basic decision to make here about the nature of reality. Well, then how can the academy, how can you academics just ignore it?

- Well, so, okay, so I don't know why and like David-

- But I hold you responsible, Sergiu.

- I don't want to talk about issues of existence, ideas, platonic ideas. Maybe, it's a step too far and that may be what we agree, but I have a operational definition of reality. So reality is consistency of representations of a particular object. I mean, that's true in physics, and that's true in mathematics. Mathematical objects are real. A mathematician who works on a mathematical problem, calculates in this way, calculates in that other way, always gets the same result. I mean, there's something so obviously objective about what we do, right? That somehow to claim that these are just inventions of the human mind is ridiculous to me. I mean.

- There is a way to defend any position in philosophy. I mean, we could argue that there are inventions of the human mind because the human mind is the only thing that really exists. After all, there's a very noble tradition going right back to Berkeley, which makes exactly that case, "To be is to be perceived" But there is something that inhibits a return to Berkeley and idealism in that it sounds vaguely preposterous to say the only thing that exists is a mind. It doesn't comport with the magnificence of the physical theories weeped about. It just doesn't. That's not an argument, it's an observation. But having said that, we are really in danger of being reduced to an ever-narrowing ice flow. The ice flow, as Sergiu just mentioned, is the consistency of representation. Well, representations is kind of an obscure term. Why don't we get down to basics? It's the consistency of our theories. Well, what is the theory? Well, we can provide an answer to that. A theory is kind of a large group of sentences. And what are sentences? There are things that make certain kinds of assertions that can be true or false enough, they're consistent. That is about as good as we can get in terms of the credibility and commendability of a theory. So we're reduced now and our ice float is saying, "Well, we have a representation or a theory about the physical world and it's consistent, but when we examine it, we find out it is not a physical object." It invokes non-physical substances like mathematical objects. We don't have to say, "We need not make a decision, do they exist in the mind or they exist in the external world, they exist," that's all we need. The number two exists. I don't have to tell you, it exists in your mind exists, it exists in my mind, that's an irrelevant, it exists. That's the determinative statement. And as long as it exists and we acknowledge it's not physical, then we're left with a position of saying, "How come our best view of the physical world incorporates things that are not physical? Why is that?"

- Existence is an autological question, I prefer reality is something that I can work with. Well, existence, I don't know. When it comes to usually existence, I feel lost, right? I don't exactly-

- You feel lost.

- I mean, I don't know what existed, what does not exist.

- What intrigues me in all this is the idea that those mathematical objects, whether it's the quadratic equation or a circle or more advanced forms of mathematics, have stable properties. When they-

- Because this is the consistency you're talking.

- I'm talking about reality, yeah, reality and objectivity.

- [Stephen] Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

- Consistency.

- Yeah, what Sergiu was saying is that these mathematical structures or objects have a reality that's independent of whether or not I affirm those properties myself. They're mind-independent and yet, they're conceptual, essentially. They're not material, they're conceptual. So it does raise the question, where do they reside? If there are concepts, and this is where we're moving in this direction by bringing Plato in. Plato had the idea that there are conceptual realities that exist in some sort of, you know, heavenly realm. But Aquinas's critique of that was, that's not consistent with our experience. Ideas exist in minds. There are these objective properties of mathematical structures, they're independent of our minds. And if these mathematical structures are themselves conceptual, it implies not that they're floating around someplace, but they originate or reside fundamentally in some transcendent mind. That's the theistic take on the mathematical realism.

- Steve says, math exists in the mind of God. And Sergiu says, "Uh, don't bother me with that, I'm a working mathematician. All I need is this piece of chalk and a blackboard."

- Well, operational definition of reality, right? And the notion that somehow everything that's real, it's physical, it doesn't make sense to me because mathematical objects are also real.

- And I think we're all saying you know, where you slice this, whether you're a-

- Yeah, I think that's absolutely right. I mean, even if we adopt Berkeley's position, that to be is to be perceived, we wind up at the same position that a thoroughly consistent and coherent view of the universe simply can't be physical.

- [Peter] Yeah.

- It simply can't be clear.

- We agree, okay. That actually strikes even my little mind as a really quite profound, I'm not going to call it an insight, it's a discovery, it's a real aspect of reality itself.

- Can I revert back to something earlier in the conversation?

- Sure. It's just something from David's book, he gave a talk in the U.S. on this one time, and it just was so intriguing to me. I think it was from your book, "One, Two, Three," when you were talking about it on the road. I think it was the complex variables. The complex numbers, remember, the square root of negative one from math, there's this whole mathematical apparatus that's been developed around complex numbers. And it seems like it has absolutely nothing to do with anything, but there's a whole body of mathematics on this, I took a course in grad school on complex variables. And David showed that this was invented something like, what was it, 140, developed, discovered.

- 140.

- [Stephen] 140 years before.

- Maybe 200, maybe 200.

- Yeah, and then lo and behold, it's absolutely crucial for doing quantum mechanics, which is our most fundamental physical theory or one of them.

- No, but if I can.

- Yeah, please correct me.

- What is fascinating about the history of the invention of the number I is that, well, it came up in Italy around, you know, 14th century.

- 16th century.

- No, earlier, I think, 1450.

- [David] Yeah.

- Okay, 1450, a bit earlier maybe. But in any case, it was based on their desire to solve equation. So they wanted to solve first a quadratic equation, there was a formula already. The Arabs apparently also knew it already. In any case, they went to the third order equation and they found that it based to introduce this symbol, square root of minus one, which makes no sense, you cannot take the square root of minus one, right?

- Makes no sense to me.

- But they just put it there and they made this incredible observation that you can use this number and at the end, you are getting a solution of cubic equations, which are all reals and nothing to do with those complex numbers, but they enter into the formula. So this was quite an amazing thing, right? So then little by little, they got used to using square root of minus one. And at some point in the 19th century, it was even made more formal, it was given a geometric definition of square root of minus one. And you have complex numbers and complex functions and then the enormous amount of applications came out of it. So square root of minus one is obviously real, it existed before it was discovered by-

- That's very interesting.

- When they introduced negative numbers, I stopped paying attention. Negative numbers have nothing to do with reality, but I was wrong then.

- Peter, it's not negative, these are complex numbers. The square root of minus one, the negative numbers of minus one, minus two, think of debts. We're not talking about debts now, we're talking about a complex number. But here's the extraordinarily interesting point, you got this weirdo, Italian mathematician in the 15th century who figures out that if I introduce the symbol I equals the square root of minus one, I can solidify a chain of inference and come out with the right answer. Just absolutely amazing. However, when mathematicians start to think about it, it's entirely possible to get rid of the square root of minus one in favor of two real numbers and a set of rules for manipulating them. All of a sudden, the square root of minus one is gone. You're left with what you began with, the real numbers, three and seven in a certain order and obeying certain rules.

- A multiplication rule, which is essential.

- [David] Yeah.

- So that's the complex number.

- The complex number, exactly.

- It's a new multiplication rule, which did not exist in the realm of what is called, real natural numbers.

- But that interests a very interesting analytical point that ontology can be reduced in favor of a system of rules and regulations. You can reduce the ontological burden of mathematics. You can say, I'm going to get rid of the numbers in favor of the sets. I'm gonna get rid of the complex numbers in favor of ordered pairs of real numbers. I'm gonna get rid of the real numbers in favor of convergence sequences. I'm gonna get rid of so much. But as you reduce the burden of ontology, you increase the burden of your regulations. So you actually never get to the point where mathematics appears from nothing. You never get to that point. Like a biologist-

- Ontology just being the affirmation of something substantially real.

- I mean, biologists love to say, life comes only from life. 19th century, it's obviously true. Life comes only from life. And how it might not come from life is an utter mystery. But it's also true that language comes only from language. And it's additionally true that mathematics only comes from mathematics. These seem to be processes with which we have a good deal of experience, which have no point of origin. There is no place in which mathematics originates. There's no place in which language originates and there is no place in which life originates. They may well be fundamental features of the universe itself,

- But nevertheless, mathematics has a history. And this article...

- But it's infinite in the past.

- [Sergiu] Right.

- It's always been.

- It's a human. So there is something human about mathematics.

- There's a history of our discovery, but not a history to the realities.

- Exactly.

- Okay. David, this is a conversation you had, I think with Steve in Cambridge. I'm gonna quote a passage. "Hold up a finger. Could this finger be a different color? Yes. Could it be slightly longer? Yes. Could it be crooked? Yes. But could it ever be anything other than one finger? No, the number is obligatory. The number is something the finger essentially has." All right, so now we're in the realm of Aristotle and the difference between essence and-

- Essential properties and non-essential properties.

- And accidents. Essential properties.

- Yes, exactly.

- And accidents, explain this.

- Well...

- I feel as though I'm tiptoeing-

- You're doing well, Robinson.

- All right, all right. So numbers represent an essential aspect of reality. That's a big deal.

- Well, it's a very general statement. I much prefer, God forbid me, forgive me for introducing Heidegger, I much prefer his formulation. Heidegger, there are very interesting passages in his work. I admit it, and he says, "Look, when we look at objects, we cannot separate the oneness of this glass from the object itself. But we can change the color, we can change the shape. It'll still be the same object, but we can't say this one object could have been two. That just doesn't go." So when we talk about physical objects, we're only talking now about physically realizable objects. The mathematical aspects are essential to them. What holds for numbers also holds for shape. We don't have to do what Eugene Wigner did and say, "Look at quantum mechanics and the remarkable fact that Hilbert spaces require introduction of complex numbers." No, just look at the glass. The glass requires the introduction of a natural number. Two glasses require the introduction of two natural numbers. That is every bit as mysterious as the invocation of complex numbers and quantum field theory. Every bit is mysterious. And we don't know quite why.

- Okay, so all three of you are willing to agree, all three of you are willing to insist that mathematics, the existence of mathematics, the weird way in which mathematics seems to correspond with and help us to investigate reality in a way that is real. I'm using reality over and over again, proves that reality is not purely, not limited to what we can access by our five senses.

- It's a hint. It doesn't prove, it's a hint.

- Oh, now I've lost deep ground even from that all, so all we have is a hint. I think Steve is willing to go, now here, I'm putting words into Steve's mouth. Steve is willing to say, "We're dealing here with the mind of God." And David won't do that, I could pin you down and you wouldn't.

- I'll give you sort of an example of something like this. So, you know, immediately after Newton, there was Newtonian mechanics. The idea was that Newtonian mechanics has to explain everything. Then came Maxwell, the Maxwell equations. And in order to adjust the Maxwell equations to Newtonian mechanics, they needed this notion of ether, right? So, you know, ether here is that there. I mean, Einstein's great insight was, we really don't need it, right? So it's the same thing, I believe, we don't need this materialistic representation of the world. Just forget about it. Reality means something broader than that.

- It's inconsistent with the most obvious presentation of mathematics itself. It's obvious that mathematical properties are not material. You can invent a metaphysical system that explains that away. That's why it's not approved.

- So nobody proved that ether does not exist.

- [Stephen] Yeah, yeah, right.

- We just get rid of it.

- [Stephen] Yeah.

- And I think that's what we should do about material.

- I think I could agree with that, but going back to your last remark, Peter, I think it's just much simpler to say that the mystery is just the existence of mathematics. It's just that. Because it's fundamental. We could well say, and of course, philosophers have well said, we can get rid of the physical world, metaphysically, that's not a problem. Berkeley showed how everything is a perception or an idea. External world just disappears. But we can't get rid of the mathematical world, that's ineliminable and its existence is a profound mystery. What is it doing there? Why do we see things in mathematical terms? Now, I'm not asking this question because I have a secret answer that I'm about to say.

- I was hoping you to wrap up the conversation with the answer.

- I find it a great mystery. The sheer existence of mathematics is deeply puzzling.

- [Peter] You will agree with every word of that.

- Yeah, absolutely.

- [Peter] And you will agree, but can you take it farther?

- Well, I just am intrigued with this kind of argument that I recapitulated earlier in the conversation that mathematical objects have stable properties, therefore, they have an objectivity that is independent of our minds. And yet, they are conceptual, which suggests by our experience that they must not be floating around somewhere in the platonic heavens. But rather, it makes more sense to me to think that they ultimately issue from the mind of God. And that that is the deep reason for the mysterious applicability of mathematics to the physical world.

- Bear in mind, Steve, that you're reaching a position very close to Berkeley's position.

- [Sergiu] To whose?

- To Berkeley, Bishop Berkeley.

- [Sergiu] Right.

- I mean, if you say that to be is to be perceived.

- Bishop Berkeley's 17th century British.

- 18th century.

- [Peter] 18th century English churchman and philosopher who appears possibly most famously in Boswell's life of Johnson, when Boswell says-

- I refute Berkeley.

- Yes, thus Johnson kicking a rock. Immaterial of all this material.

- But the point is, Berkeley faced the obvious question. If you're not looking at the moon, Einstein discusses this too, does the moon continue to exist? And Berkeley's response was, "Yes, it exists as a thought in the mind of God." Which is very close to what Steve was just argue. Although, he's certainly not-

- I'm not a Berkeley.

- You're not a Berkeley.

- I don't think the physical world has, I think it has an independence of our mind and of the mind of God who created it, but I think the ultimate source of mathematical reality may well be the mind of God.

- But it's interesting that you are prepared to go further than I think many contemporary analytic philosophers are prepared to go in the direction of a Berkeley kind of analysis, which I think is in this case, the only analysis that makes sense.

- At least for math.

- [David] Yeah.

- At least for math, because it is so mysterious.

- Boys, I'm going to attempt for last question here. I'm going to attempt to introduce one new concept, and that is the concept of beauty. I have no idea how this will go, but here's an excerpt from the forthcoming documentary, "The Story of Everything." There's something in science called, the Beauty Principle that says, true theories often convey a mathematical beauty or a structural harmony. Upon looking at their model of the DNA molecule, Francis Crick was quoted as saying, "It's so beautiful, it's gotta be right."

- Explain that. Why should beauty enter into this?

- We don't really know. But it tends to be what's called, a heuristic guide in science, "A Guide to Discovery." And in the section of the film that follows, there were maybe perhaps even more trenchant comments from a couple of the physicists who are saying how often their perception of mathematical beauty had been a guide to discovery. I think it was Paul Dirac who first said that it's more important for the theories.

- Yeah.

- They're more beautiful than to have them consistent with the data, well, because we can be mistaken about how we're perceiving the data. But there is assumption that there's something mathematically beautiful about reality itself. Intelligibility.

- Dirac was mesmerized by somebody-

- [David] I'm sorry, who?

- [Stephen] Dirac. I said, Dirac, yeah. Dirac was mesmerized.

- And you said a moment ago when you were choosing projects on which to work, I think you used the word, is it elegant, is it beautiful?

- [Stephen] Aesthetic.

- Of course, yeah. The Kerr solution is an incredible object. I mean, really beautiful.

- Are we on another mystery here? An aesthetic mystery.

- Beauty plays a fundamental role, of course, in the way we choose problems, but also in the way we are guiding ourselves towards the truth. I mean, towards a solution of a problem. Somehow, we reject arguments which are contrived, which are not beautiful. We don't call them beautiful. Yeah, I mean, it's mysteriously true. And physics, of course is full of such examples. Maxwell, you know, the way the Maxwell equations were discovered, it was first Faraday who had the three laws of electro minorities already discovered experimentally.

- [Stephen] That's right.

- But he was not a mathematician at all. So he just left it there, just stated the laws. And it was Maxwell who realized that if you put those statements within mathematics, there's a lack of symmetry, sort of guided him towards a force one, which led to electromagnetism.

- And all of the technology of the modern world.

- [Sergiu] Beauty.

- With Maxwell.

- Your comment about beauty.

- Yeah, I'd like to hear from these guys 'cause yeah.

- I kinda reserve that for my tailors.

- You know, I can tell you that as a working mathematician, it plays absolutely a fundamental role in everything people do.

- [Stephen] Really?

- There are very few mathematicians who would say, "I work on this because it's just ugly," right? I mean, you know, they choose the problems, the directions based on aesthetic-

- That's just a party line, Sergiu, there are all sorts of mathematical drabs that we keep hidden. Nobody's gonna tell me, turbulence is a beautiful subject.

- Oh, it's a fantastic subject.

- Fantastic, but not beautiful, clumsy, lumbering.

- Well, but the expectation is that we'll find the beauty in turbulence by some discovery.

- Expectations are easily purchased, beauty comes at famine prices.

- All right, kick him because he's being perverse now. He's being mischievous. Last question, Isaac Newton, the man who gave us mathematics on astronomy, fluid dynamics.

- The calculus

- And Newton explains a lot. Here's a quotation from Newton. "A heavenly master governs all the world as sovereign of the universe." A recognition of the divine, or a mind that transcends our own is taken for granted for thousands of years. As recently as Newton, and then it gets kicked out of intellectual life and kicked out of the academy. Does the mystery of mathematics suggest that the materialist error was an aberration that ought to and may be ending now? Are you willing to go that far, Steve?

- No, of course. I think that's exactly right. And what Newton illustrates so beautifully is this principle of intelligibility that we've been talking about, that the mathematical rationality that can be developed by mathematicians without necessarily observing nature, does then apply to understanding the rationality that's built into nature. And this was so crucial to the period of the scientific revolution when the systematic methods for interrogating nature, for studying nature were developed and culminating in figures that maybe is no figure like Newton, who was so profound in his insight and who advanced what was called, natural philosophy or science so much in one generation, even in one year, his fame, Annus Mirabilis, where he went home during the plague to remediate his own deficiencies in mathematics and came back having invented the calculus. You know, so.

- A heavenly master, David.

- What can I say? That insight has not been vouched safe to me.

- Fair enough.

- Sergiu.

- Well, okay, so first of all, I think material, I mean, materialism is just the only explanation of the world, it should be put in a ash bin of history. And that we both agree.

- Yeah.

- Bringing God in, sure, why not? I mean, that's another way of looking at the world. If there's something else, well, let's find out. Maybe, there is another explanation, but at this point, I don't see any reason why you should not look at that possibility.

- So God exists. And why not?

- Right?

- Sergiu Klainerman, David Berlinski, and Steven Meyer, gentlemen, thank you.

- It's been our privilege, Peter.

- For "Uncommon Knowledge," the Hoover Institution and Fox Nation, I'm Peter Robinson.