- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

Shortly before the 1994 midterm elections, when House minority leader Newt Gingrich began talking about a coming Republican takeover of Congress and outlining plans for his speakership, David Dreyer, a White House aide, remarked, “He’s done Lord Acton one better. He’s corrupted by power he doesn’t yet have.” After election day it was Dreyer who had egg on his face. The Republicans did take over the House and the Senate, controlling the two for the first time since 1955—and by a broad enough margin that they seemed likely to hold both houses indefinitely. Everyone spoke of a “revolution”—politicians and the wider public, those who favored and those who feared one. Pundits resurrected the decades-old metaphor of the political analyst Samuel Lubell, according to which America has essentially a one-and-a-half-party system. One party is the sun, illuminating all the planets. The other is the moon, giving off only reflected light. For the first time since before FDR’s election, it looked as if Republicans were the sun and Democrats the moon.

Today Dreyer and others who scoffed at a Republican ascendancy seem likely to have the last laugh. There has indeed been a movement to the right on some issues, but it has not translated into a partisan shift. A stunning mid-1997 ABC/Washington Post poll that asked voters, “Which party do you trust more to . . . ,” shows the Democrats besting the Republicans on practically all issues, including such Republican staples as taxes, crime, and budget balancing:

| Democrats | Republicans | |

|---|---|---|

| Which party do you trust more to: | ||

| Improve education? | 51% | 30% |

| Help middle class? | 51 | 30 |

| Handle economy? | 43 | 39 |

| Hold down taxes? | 41 | 38 |

| Balance budget? | 39 | 36 |

| Handle crime? | 38 | 34 |

| Handle foreign affairs? | 38 | 40 |

| Reform campaign finance? | 34 | 31 |

| Maintain strong defense? | 32 | 50 |

Suddenly it looked as if either the 1994 election was a fluke or the 104th Congress had done something dramatically wrong. The Republicans have narrowed the gap in party registration until they’re only four percentage points behind the Democrats (39–35), but the Democrats still lead on the issues. The Republicans hold a majority in Congress, but that Congress has been trumped by a Democratic president on every major policy initiative of the past three years. And when a midwinter sex scandal initially sees the president’s job-approval ratings rising to about 70 percent, the Republicans have cause for worry. There is now no sense in which they are the sun of American politics. Far from it: they are a majority giving rise to second thoughts among those who made them one.

This is something the Republicans seem not to realize. Their party was thrashed in the 1996 national elections. In presidential politics they were stuck on the Goldwater-McGovern-Mondale landslide-loser plateau of 40 percent, as they had been in 1992. They lost nine seats in Congress. Yet the party is approaching the 1998 election as if it had won the last time out. Republicans of all persuasions view their party’s problems as temporary, remediable through either ideological fine-tuning or image buffing and spin. Certain Republicans—particularly cosmopolitan governors on the East and West Coasts, such as Christine Todd Whitman of New Jersey and Pete Wilson of California—claim that the party has moved too far to the right and that its stances on social issues, notably abortion, are driving away centrist voters. Others—particularly those at Christian organizations, such as Gary Bauer of the Family Research Council and James Dobson of Focus on the Family—say it’s too far left, lacking the guts to assert itself on family dissolution and related family-values issues on which the public is in its corner. Still others—among them such class of ’94 congressional firebrands as Steve Largent of Oklahoma, Linda Smith of Washington, and Mark Neumann of Wisconsin—say that the party has ignored centrist, reform party–style outrage and made itself a campaign finance–swilling incumbency-protection machine. Another line of thinking is that the party has merely been victimized by accidents of personality: the mysterious ability of Newt Gingrich to generate loathing and of Bill Clinton to generate support.

Republican problems go deeper than that, however. The party faces a crisis of confidence that has many symptoms—repudiation in the most sophisticated parts of the country, widespread distrust of the Republican leadership, an inability to speak coherently on issues. All of them grow out of the same root cause: a vain search to rediscover the formula that made that unformulaic president Ronald Reagan so broadly appealing—even beloved. Congressional Republicans triumphed decisively in 1994 on such Reaganite issues as free trade, welfare reform, and shrinking the government. But, thanks to a deficit-dissolving economy and a dwindling memory of the Cold War, those issues were of declining importance even then and have since given way to a bipartisan consensus. Consensus, of course, is only another way of describing the issues that have been taken off the table. What remains for the party to talk about? On first thought, not much. The Republican strategist Ed Gillespie says, “We’re like the dog that caught the bus.”

Now that there is no longer any force on the political landscape to challenge their general principles, the Republicans are clinging to power, even as they grow confused about what exactly they are supposed to do with it. They are infuriating voters by blaming them at every turn for the party’s failure to win their hearts. In other words, the Republicans are looking more and more like the Democrats of the 1970s and 1980s and less and less like the party that overthrew them.

STOLEN BASES

Since the 1960s Republican gains at the national level have been built on two trends. One is regional—the capture of more and more southern seats. The other is sociological—the tendency of suburbanites to vote Republican. The party’s 1994 majority came thanks to a gain of nineteen seats in the South. In 1996 Republicans picked up another six seats in the old Confederacy. But that only makes their repudiation in the rest of the country the more dramatic. The party has been all but obliterated in its historic bastion of New England, where it now holds just four of twenty-three congressional seats. The Democrats, in fact, dominate virtually the entire Northeast. The Republicans lost seats in 1996 all over the upper Midwest—Michigan, Wisconsin (two seats), Iowa, and Ohio (two seats). Fatally, they lost seats in all the states on the West Coast. Their justifiable optimism about the South aside, in 1996 it became clear that the Democratic Party was acquiring regional strongholds of equal or greater strength.

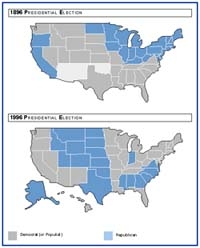

As Walter Dean Burnham, a political scientist at the University of Texas, has noted, the 1996 elections almost diametrically oppose those of 1896. (See accompanying maps.) Anyone who is today middle-aged or older was born in a country with a solidly Democratic South and a predominantly Republican Midwest and Northeast and probably will die in a country in which the Republicans hold the old Confederacy and the Democrats dominate from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic. In effect, the two parties have spent the twentieth century swapping regional power bases.

Since it is the southern and mountain states—the Republican base—that are adding voters, congressional seats, and electoral votes, this constituency trading was supposed to be all gravy for the Republicans. It isn’t. The bad news for the party in 1996 was not so much regional as sociological. In the suburbs—home to 40 percent of voters, by conservative estimates—Clinton ran even with Bob Dole. Clinton won among eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-olds in 1992 and 1996, reversing Reagan and Bush victories among that cohort in 1984 and 1988, and he also won among Catholics, who had voted Republican in the three previous elections. (In Congress the Republicans won the Catholic vote for the first time ever in 1994; one election later they were routed, by 53 to 45 percent.)

And the Republicans lost heavily among Hispanics, America’s fastest-growing voting bloc, who added 1.5 million voters from 1992 to 1996 and will probably add as many again by the next presidential election. This alarming result confounded an earlier Republican optimism. Democrats who had arrogantly assumed that standard-issue minority politics would easily pull Hispanics into the party fold were proved wrong throughout the 1980s. Hispanic voters turned out to be disproportionately entrepreneurial and disproportionately receptive to Republican family-values rhetoric and gave the party roughly a third of their votes in the three presidential elections from 1980 to 1988. Leaving aside Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in New York, who do fit the Democrats’ minority paradigm, the Republicans were doing better with the Hispanic vote than might be expected.

But the Republicans in the 104th Congress tried to shore up their Texas and California right wings with hostile rhetoric on immigration. They passed legislation that sought to deprive not just illegal but also legal immigrants of federal benefits. (Newt Gingrich and other Republicans backpedaled in 1997, reversing some of the measures, but the damage was done.) And California’s Proposition 187, supported by Republican governor Pete Wilson and aimed at denying benefits to illegal immigrants, brought angry Hispanics to the polls in unprecedented numbers. Clinton took 72 percent of the Hispanic vote nationwide, including 81 percent in Arizona and 75 percent in California; he took 78 percent of Hispanics under thirty. He nearly split the Hispanic vote even in Florida, where 97 percent of the Cuban population voted for Reagan in 1984.

THE FINKELSTEIN BOX

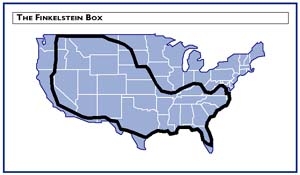

These sociological and geographic shifts are part of a broad change in party allegiance. No one has been more astute in outlining its nature than the Republican consultant Arthur Finkelstein, who set the pattern for Republican triumphs in the 1980s by running aggressive, ideological campaigns that went after Democratic candidates for their uncommonsensical liberalism—a word that was repeated almost hypnotically in the ads and speeches he wrote.

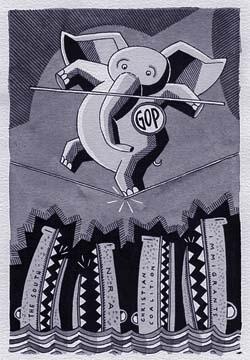

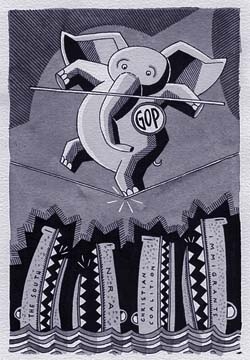

Finkelstein uses a simple graphic device (see map) to show his Republican candidates just how differentiated the country is geographically. In the states that have their largest population centers outside the box, no Republican senatorial candidate got a majority in the last election. Inside the box, no Democrat got a majority except Mary Landrieu of Louisiana (and that barely). Although most Republican governors outside the box are pro-choice, almost every Republican governor inside the box is pro-life.

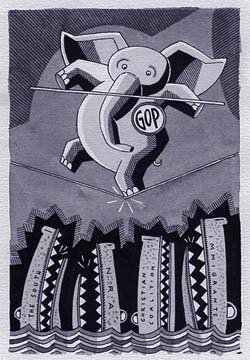

The Republican Party is increasingly a party of the South and the mountains. There is a big problem with having a southern, as opposed to a midwestern or a California, base. Southern interests diverge from those of the rest of the country, and the southern presence in the Republican Party has passed the “tipping point” and begun to alienate voters from other regions.

The most profound clash between the South and everyone else, of course, is a cultural one. It arises from the southern tradition of putting values—particularly Christian values—at the center of politics. This is not the same as saying that the Republican Party is “too far right”; Americans consistently tell pollsters that they are conservative on values issues. It is, rather, that the Republicans have narrowly defined values as the folkways of one regional subculture and have urged their imposition on the rest of the country. Again, the nonsoutherners who object to this style of politics may be just as conservative as those who practice it. But they are put off to see that “traditional” values are now defined by the majority party as the values of the U-Haul-renting denizens of two-year-old churches and three-year-old shopping malls.

The bet that Republicans are making is that the South will add congressional seats and electoral votes faster than the rest of the country will grow alienated from the party’s southern message. Most members of the party are content with this arrangement, but they’re also hoping that the South can be transformed enough to keep voters elsewhere from fleeing the party in droves. “I think the South is a new South,” says the Republican strategist Arnold Steinberg of California. “You’ll see southern cities that are more progressive.”

“On the other hand,” Steinberg admits, “the North doesn’t exactly realize that.”

ACLU REPUBLICANS

It’s understandable that voters have found Republicans “frightening,” given the dovetailing of southern Republican antigovernment rhetoric with that of right-wing terrorists. From this standpoint the two signal events of the 104th Congress were the Oklahoma City bombing, on April 19, 1995, and the government shutdowns of 1995–1996, advanced in a belligerent rhetoric of “revolution” that Americans distrusted.

The single most destructive interest group on the right is the NRA. Representative Henry Hyde, an Illinois Republican, holds guns—not abortion—to blame for the gender gap.

On the morning that Timothy McVeigh sent hundreds of innocents to their graves, the lead story in all the major newspapers was President Clinton’s disastrous speech of the night before, the low point of his entire presidency, in which he argued pathetically that he was still “relevant” to the country’s politics. Clinton’s numbers quickly began to turn around. Newt Gingrich’s popularity, meanwhile, remained strikingly low. Gingrich called “pathetic” the media’s conflation of his “revolution” and McVeigh’s. But the court of public opinion is not a court of law, and politicians who show too much overlap with a force that Americans consider a genuine menace are punished for it, as the Democrats were during the Cold War.

And, like the Democrats of the seventies and eighties, the Republicans in the aftermath of Oklahoma City compounded the problem through their nitpicking libertarian indifference to Americans’ fears about armed violence. In thrall to their supporters in the National Rifle Association, the Republicans were soon trying to repeal a 1994 assault-weapons ban, after a brief postbombing breather. And what could be more like the Democrats’ “coddling of criminals” circa 1975 than the Republican attack on “taggants” in the 1996 terrorism bill? Congressional Republicans, in the name of the Second Amendment, fought to prevent the use of chemicals that would allow plastic explosives to be traced. This kind of procedural excuse for letting murderers walk led one analyst at the conservative Heritage Foundation to coin the term ACLU Republicans.

An apt parallel. If Christians are the blacks of the Republican coalition, then the NRA is its ACLU. The Republicans are not yet as beholden to their special-interest groups—their marksmen, polluters, and plutocrats—as Democrats are to their teachers’ unions and race agitators, their feminists and ambulance chasers. But guns are special. The bipartisan political consultant Dick Morris maintains that the single most destructive interest group on the right is the NRA. Representative Henry Hyde, an Illinois Republican, holds guns—not abortion—to blame for the gender gap. Rabidly progun rhetoric has succeeded in putting the Democrats on the side of the cops and crime control, Republicans on the side of criminals and crime. Suddenly, in the wake of Oklahoma City, Americans noticed that it was conservatives, not liberals, who assailed the FBI and railed against putting 100,000 cops on the streets. It was the NRA, not the ACLU, that was raising money by attacking the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms as “jackbooted thugs.” Today it is the right, not the left, on which suspicion falls first whenever a bomb goes off. The identification of Gingrich with McVeigh may have been excessive, but there was no denying that sometime since the Reagan administration the Republicans had replaced the Democrats as the To-Hell-in-a-Handbasket Party, the party more congenial to haters of America.

THE HILLARY CLUSTER

There is an ideological component to Clinton’s success and the Republicans’ failure. The end of the Cold War, the increasing significance of information technology, and the growth of identity politics have caused a social revolution since the badly misunderstood 1980s. It’s difficult to tell exactly what is going on, but in today’s politics such subjects for discussion as communist imperialism and welfare queens have been replaced by gay rights, women in the workplace, environmentalism, and smoking. On those issues the country has moved leftward. In 1984 the Republicans held a convention that was at times cheerily antihomosexual, and triumphed at the polls. In 1992 the party was punished for a Houston convention at which Pat Buchanan made his ostensibly less controversial remarks about culture war. Reagan’s Interior secretary James Watt once teasingly drew a distinction between “liberals” and “Americans” while discussing water use and pushed a plan to allow oil drilling on national wildlife refuges. By 1997 the New Jersey Republican Party was begging its leaders to improve the party’s image by joining the Sierra Club.

This is in part a story of how successful parties create their own monsters. Just as Roosevelt’s and Truman’s labor legislation helped Irish and Polish and Italian members of the working class move to the suburbs (where they became Republicans), Reaganomics helped to create a mass upper-middle class, a national culture of childless yuppies who want gay rights, bike trails, and smoke-free restaurants. One top Republican consultant estimates that 35 to 40 percent of the electorate now votes on a cluster of issues created by “new class” professionals—abortion rights, women’s rights, the environment, health care, and education. He calls it the Hillary cluster.

Reaganomics helped create a mass upper-middle class, a national culture of childless yuppies who want gay rights, bike trails, and smoke-free restaurants.

And with this new landscape of issues Republicans aren’t even on the map. Because of the Reagan victory, the Democrats went through the period of globalization and the end of communism amid self-doubt and soul-searching. The experience left them a supple party that quickly became familiar with the Hillary cluster. Bill Clinton’s ideology here is necessarily an inchoate one, and in his heart of hearts he may be to the left of where the country is. But he is the first president to understand that the Hillary cluster is not on one side or the other of a partisan fault line (and that is his greatest contribution to American politics). The American people are not “for” or “against” gay rights. They overwhelmingly say they favor equal rights for gays—but then draw the line at gays in the military. They’re for AIDS research funding—but think gays are pushing their agenda too fast. Americans aren’t for or against environmentalism. They believe that global warming is going on—but waffle on whether major steps should be taken to block it. They have shown a tolerance for paying more taxes to protect the environment, but few list it as their number one concern when asked by pollsters.

Such jagged political fault lines make Americans’ ideology look ambiguous by old definitions. In fact, the Boston University sociologist Alan Wolfe doubts whether the old polarity of conservatives and liberals is any longer meaningful, at least on the increasingly important cultural issues. The big question is whether this blending of conservatives and liberals is happening at the party level—whether President Clinton has effected a wholesale change in his party. Ed Goeas and other Republican pollsters say there’s no indication that Clinton is enticing people back to the Democrats. The best evidence, however, from 1996 exit polls is that the Democrats are no longer a liberal party—or at least they are far less liberal than the Republicans are conservative. Whereas 58 percent of Republicans identify themselves as conservative, only a third of Democrats identify themselves as liberal.

To the Republicans, it doesn’t much matter. They’ve missed all of this and continue to campaign against the Democrats they wish they were contesting: against Jimmy Carter and his economy, against George McGovern and his foreign policy, against Jesse Jackson and his urban policy. They treat the past two presidential elections—the worst back-to-back disasters that either party has suffered since Roosevelt clobbered Herbert Hoover and Alf Landon in 1932 and 1936—as aberrations, much as certain Democrats throughout the eighties insisted that the only “typical” elections since Truman were in 1960 and 1976.

The Republicans are too conservative: Their deference to their southern base is persuading much of the country that their vision is a sour and crabbed one. But they’re too liberal, too, as their all-out retreat from shrinking the government indicates. At the same time, the Republicans have passed none of the reforms that ingratiated the party with the “radical middle.” The Republicans’ biggest problem is not their ideology but their lack of one. Stigmatized as rightists, behaving like leftists, and ultimately standing for nothing, they’re in the worst of all possible worlds.

That’s why the Republicans spent months waiting for a Clinton scandal to blossom. Like the Democrats of the 1970s, they are now the party with a stake in institutional disruption and bad news. And their resemblance to the corrupt dynasty they overthrew does not stop there. Their party is now directionless, with only two skills to recommend it: first, identifying and prosecuting the excesses of its opponents; second, rigging the campaign finance system to protect its incumbency long after it has ceased having any ideas that would justify incumbency. The Republican Party is an obsolescent one. It may continue to rule, disguised as a majority by electoral legerdemain. But it will be a long time before the party is again able to rule from a place in Americans’ hearts.