- Education

- World

- Military

- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Energy & Environment

- History

There is great truth and beauty in Homer’s Iliad, but I wouldn’t try to sell it to readers with such platitudes. Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire remains a classic, but I confess it can be hard to get through. Conrad’s Victory or Knut Hamsun’s Growth of the Soil, if they were written by this year’s writer X, would be trashed on Amazon.

So what are the reasons, in this age of the iPhone, Xbox, and PlayStation—or Fox News blondes and HBO—to sit down and read old stuff for an hour or two each week? Here are a few that go beyond the usual defense of the classics, the canon, and the glories of Western civilization.

A MENTAL WORKOUT

The mind is a muscle. Without exercise, it reverts to mush. Watching most TV or using the normal electronic gadgetry doesn’t tax us much—indeed, that is its very purpose: to eliminate effort, worry, unease, and afterthought. None of us thinks back to a great videogame session of a year ago. Few can recall the Super Bowl winner of 2001. I remember scenes in a Shane or a Casablanca, but few others among the thousands of movies I have watched.

By nature, our ways of expression and even thinking fossilize and wither away with age and monotony—a process accelerated by the modern electronic age and the neglect of replenishment through reading. The actual vocabulary of our present youth seems to me reduced to about a thousand words or so. “Like,” “whatever,” “you know,” “cool,” and other pop culture fillers substitute for entire phrases, a sort of modern porcine grunting. The Greeks used particles to accentuate vocabulary and guide syntax; we use them instead of vocabulary. How did incomprehensible slang, spiced with vulgarity, become something to emulate? I used to hear farmers without college degrees speak wonderful English; now, listening to a member of Congress almost requires an interpreter.

Reading alone enriches our vocabulary. It teaches us that good writing requires a sense of melody as well as a command of grammar. Thus the well read become the well spoken.

HITCHENS AND THE MASTERY OF WORDS

Think for a minute: why did the right often ignore the contradictions of the late Christopher Hitchens, and the left limit its anger at him? He was not necessarily a classically beautiful stylist, and could be needlessly cruel. He wrote no great history, no great novel, no great single essay that we can instantly recall in the manner of an Orwell or Chesterton. But Hitchens surely was a rare and gifted writer, polemicist, and savant. To read eight hundred words of his was to learn something new.

Even in his most ridiculous rant, a nugget of wisdom could be uncovered. A reference to an obscure Eastern European politician might appear side by side with a line from Wordsworth—and the citation would make a better illustration of his argument, not just showcase his erudition. He mastered the odd, even perverse turn of phrase, the ability to juxtapose the colloquialism next to Latinate pomposity, or to write a ridiculous ten-line-long sentence stuffed with punctuation that was followed by a two-word noun-verb sentence a five-year-old could have produced.

In short, Hitchens was a voracious consumer of texts, and the result was what the Roman student of rhetoric Quintilian once called variation: the ability to mix up words and sentences and not bore. He could hold, even shock, the reader or listener from sentence to sentence, moment to moment.

IMPATIENT AND SUPERFICIAL

But, you object, at least our current economy of expression cuts out wasted words and clauses? We think of ourselves as users of a sort of slimmed-down, electronic communication. Perhaps, but it also turns almost everything into instant, bland hot cereal, as if we should gulp down oatmeal at every sitting and do without the bother of salad, main course, or dessert. Every day that our vocabulary shrinks, our thought patterns stagnate—if they are not renewed through fresh literature or intelligent conversation. Unfortunately, these days, those who read are few and silent; those who don’t are numerous and heard. In this drought, Dante’s Inferno and William Prescott’s History of the Conquest of Mexico provide needed storms of new words, complex syntax, and fresh ideas.

In language as in many other ways, technology has deluded the modern West. Our electronic style of communication allows us to equate widespread knowledge of how to use an iPad with collective wisdom. Because a rare, inventive mind from Caltech or MIT can craft a device undreamed of in the age of Einstein, we assume that we all warrant a share in his genius, as if our generation has trumped Einstein’s.

True collective wisdom might consist of an acknowledgement of the brilliant scientific elite that gives us such miraculous things. Public schools here in California rate about forty-eighth or forty-ninth these days in nationwide testing, while most Californians seem to have their heads permanently affixed to iPhones. Do we believe that the population is smarter because we know apps or because Apple or Google has a headquarters full of engineers in the cocoon of Silicon Valley?

Access to better and better “stuff” leads to an age of arrogance, and new technology prompts an assumption that there are always better things to come. But regress—material, intellectual, or moral—can be as common as progress, if a new generation proves a poor custodian of the laws, behavior, knowledge, and learning inherited from those leaving the scene.

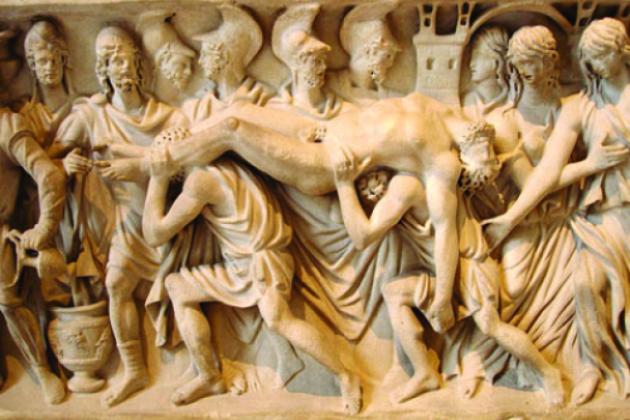

A marble relief from a second-century Roman sarcophagus depicts a scene from the Iliad : Hector’s body being brought back to Troy. The famous episode, with its themes of revenge, loyalty, grief, and doom, is one of many classic works of literature that still speak to the modern mind.

REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST

Can we see today’s problems as symptoms, as something beyond our present anguish, as challenges shared by Athenians, Romans, and Byzantines? We can—if we have some guide that turns the nonsense of today into the sense of the ages.

Lacking the awareness that ideas are old and somewhat finite, and that we are young and ignorant, we assume that each new adventure must be novel because we alone—right now!—are experiencing it. If Barack Obama would read Procopius, he would learn the wages of huge, inefficient bureaucracy. Jerry Brown, the self-described Jesuit sage, should return to his Saint Jerome, whose descriptions of an eroding Rome could just as well describe a drive down California Highway 99. (Before a crumbling society borrows billions for a high-speed rail to nowhere, it would do well to study the dusty maps of a dead generation of engineers who figured out how to finish a three-lane freeway without cross traffic.)

Reading literature endows us not just with a model of expression and thought but also with a body of ideas, as well as the names, facts, and dates we can draw on to elucidate them. When I used to follow the career of the brilliantly destructive Bill Clinton, he seemed to be Alcibiades reborn—and thus bound to share the fate of those with enormous talent who are consumed by their huge, unrepressed appetites. Richard Nixon jumped out of the pages of Sophocles, another gifted Oedipus whose innate and unaddressed flaws were lying dormant, awaiting the moment when Nemesis would take him from king of Thebes to blind beggar.

Obama? He arrived on the scene as arrogant and self-righteous as young Pentheus or Hippolytus, and now he is learning firsthand the effects of his Euripidean smugness on others.

Nothing we experience has not happened before. The ignorant miss that truth, hypnotized by sophisticated technology into believing that human nature has been reinvented in their own image. Literature helps break down that limited way of seeing the material world and ourselves. At Fresno State, I used to teach works like Xenophon’s Hellenica or Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound in advanced Greek classes, usually to about ten students. When my students translated or sounded off about Prometheus’s pontifications or nearly wept at poor Theramenes being dragged off to his death, all difference disappeared. What we had in common vastly outweighed our class, gender, and racial distinctions. Thucydides’s writings could belong to an immigrant from Oaxaca as much as they did to me—or even more so.

AGELESS WISDOM

I’m not calling for us all to be academics or scholastics with our noses in books, but to match physicality and pragmatism with occasional abstraction and reflection from the voices of the past—just a little, now and then, to remind us that Twitter or Facebook speed up communication but can slow down thought.

Literature and history call to us all, and belong to all. Somehow we must convince this new, wired generation that speaking and writing well are not the mere DSL lines of modern civilization but the keys to self-mastery, a sort of non-digital code one takes on—in addition to others, moral and legal—to uphold the standards of culture itself. A way to keep alive for one more generation the work and ideas of our long-gone betters, as if to say, “I did my part, according to my time and station.” Nothing more, nothing less.