- Middle East

A Door Opens in Troubled Territory

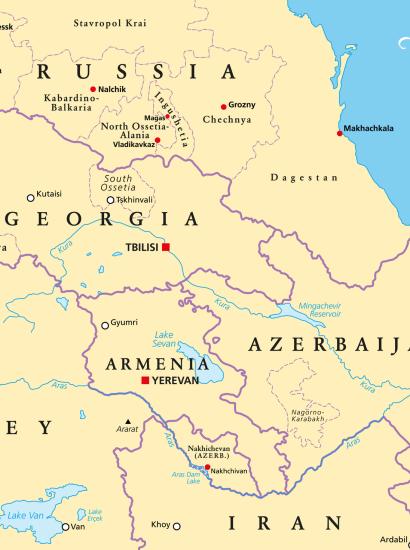

Several regions of the globe have witnessed serious and sustained disorder since the end of the Cold War era in 1991. The Horn of Africa, the Balkans, African Great Lakes: all have hosted wars, terrorism, ethnic strife, foreign interventions, intractable and flawed diplomacy. Few have seen more of it in a relatively compact area than the southern Caucasus: Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia have been particularly troubled territory over the past 35 years. The area was boiling over during the author’s initial military assignment in Erzurum, a short drive from the Soviet border in 1991 - and has not cooled below a simmer since.

The location of the Caucasus - between Iran, the Turkic lands, and Russia - has assured centuries of conflict between empires and their local allies. Two dozen wars between the Russian and Ottoman empires over hundreds of years exhausted each and brought calamity to the Armenians, Circassians, Chechens, Georgians, Turks, and other peoples caught between. Caucasian battlefields seldom lay silent - and the advent of nationalist and communist regimes in the 20th century froze without resolving the underlying conflicts. The fall of the Soviet Union reignited these - and led to a series of wars and occupations that have defied multilateral efforts at resolution. Yet the unambiguous military outcome of the most recent Caucasus conflicts - the 2020 war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Karabagh and surrounding districts of Azerbaijan with a second round in 2023 - has unexpectedly created a political opening that might end the vicious cycle altogether.

The Trump Administration had the political vision to appeal to both Yerevan and Baku to reframe bilateral peace talks away from zero-sum security formulas and towards a positive-sum trade and development logic. Both countries can benefit from the agreement initialed in the White House on August 8th of this year - through mutual recognition, renouncing violence between the two sides, ending third-party (read Russian) border security roles, and expanding trade with the United States and each other. The door is open and the path forward promising - though it is not yet clear that key stakeholders, and the Trump Administration itself, have the will and resources to turn opportunity into a new and prosperous reality. If it can, Washington and its partners will replace a mutually disadvantageous stalemate that benefited only Russia and Iran - a cynical lose/lose/win situation with the locals and the West losing and anti-Western autocracies winning. In its place will be a new status quo that expands trade, trust, and Western integration while reducing the role of Moscow and Tehran in a new win/win/lose formula - with the right sides winning and losing this time.

38 Years of Lose/Lose/Win

In antiquity, the southern Caucasus was a melting pot of small indigenous peoples - Armenians, Iberians and Albanians of Caucasia, ancestors of the Lezgins and Georgians - but became over time an arena of competition between Muslim and Christian populations as a result of Arab conquest, Turkic (Safavid and Ottoman) expansion, and then Russian imperial domination. The first major Christian/Armenian versus Muslim/Azerbaijani violence broke out on the eve of the First World War, in 1905-1906. Tensions attenuated during and after the Russian Revolution, but came to a head once again with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Armenian community of Azerbaijan actively sought union with Armenia beginning in 1987 as Moscow’s authority waned, leading to a series of intercommunal massacres in 1988 and large-scale war between 1991-1994 that resulted in an Armenian victory in the disputed Karabagh territory, occupation of 20% of Azerbaijan’s territory outside Karabagh, and an invitation for Russian troops to stay.

For 26 years following the 1994 ceasefire there was a vacuum of effective diplomacy towards a resolution acceptable to both Baku and Yerevan. Armenians declared Karabagh a new republic - Artsakh - and showed little interest in returning majority-Azerbaijani territories conquered around Karabagh, even after a four-day resumption of hostilities in April 2016 showed that Azerbaijan had rectified previous military shortcomings. Baku became home to roughly one million Azerbaijanis driven from their homes, and worked to assemble the military, political, and diplomatic resources needed to win at war what was not at offer on a negotiating table. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) led a negotiating track (the Minsk Group) that never really gained traction. Tehran and Moscow were fine with the post-1994 arrangement: no Central Asia-Europe ties through the Caucasus, Armenia dependent on Moscow but regionally isolated, Azerbaijan wounded and looking for help from a skeptical West.

In reality, the status quo in the South Caucasus after 1988 was a disaster for both sides - for Yerevan because it encouraged a false sense of security as the larger and more capable neighbor undertook significant military-technical and strategic innovations that assured a second round would go its way. For Baku the human suffering and national humiliation were painful, and the rearmament costly, while the opportunity costs for both (and for the region) were high as a result of fragmentation and frozen conflict. Yerevan and Baku were locked into a destructive stalemate - a lose/lose proposition - while Russia and Iran reaped strategic advantage, making this what we might call a lose/lose/win proposition.

The Road to 2020

The frequently-disproven platitude that war solves nothing rests on the belief that negotiations can solve nearly anything, but the lack of results from the Minsk Group stemmed from the basic asymmetry of interest in negotiations by the various sides. The Armenian side saw little reason to return lands won in battle as long as they retained military advantage - which they believed they had from the combination of strong defensive positions and the backing of Russia. Azerbaijan had every incentive to reverse the results of the 1994 settlement, and had the advantage of oil revenues, a larger population base than Armenia, and allies willing to help with equipment and expertise. The window for negotiations without a second war would close sooner than many anticipated.

Ankara was unable to provide significant military aid to Azerbaijan in the 1990s - not even transport helicopters to evacuate wounded Azeri soldiers from the fighting front to hospitals in secure areas. Turkish forces were themselves heavily dependent on foreign defense equipment, and had a far more limited capability to deploy and advise partner forces than they would have decades later. But the Turkish defense industry made tremendous advances in quality and breadth of production from 1995-2015 (and beyond), meaning high quality weapons in large quantities could supplement Azerbaijan’s previous stocks of primarily Soviet-made equipment. The Turkish military gained deep expertise in deploying and employing forces to foreign countries, and included skilled trainers and advisors. Azerbaijani officers trained at Turkish military schools, including the staff colleges tasked with developing campaign plans and operational design. As the Turkish military itself redirected from internal security missions and the military tutelary mission of the 20th century, it became increasingly professional, outward-oriented, and combat-tested. The lessons learned and skills acquired were shared with Azerbaijan forces, rendering them much more formidable than they had been in the 1990s.

Technical changes in modern warfare ensured that the next round of fighting would have a very different character than the relatively low-tech affair of the early 1990s. Unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) provided Azerbaijan with the ability to acquire, track, and strike targets. Advanced sensors enhanced combat decision-making and command and control of forces. Precision munitions allowed manned aircraft and ground forces as well as drones to more effectively engage concealed or entrenched troops and equipment. The combination of these things - officers and soldiers with better training, effective and numerous unmanned systems, improved battle management and more lethal strike options - radically changed the balance of military power between the two sides.

Turkiye was not the only ally helping to train and equip Azerbaijani forces. Israel also provided drones and intelligence support, motivated by Baku’s own staunch support of Israel in its regional struggle against Iran. The political dimension of Israeli support mattered too, as it may have tempered Congressional bias in favor of Armenia somewhat. For much of the pre-war period, the U.S. also lifted restrictions on providing military supplies or support to Baku, which had been imposed under Section 907 of the 1992 Freedom Support Act. President George W. Bush had granted a waiver after the 9/11 attacks as Azerbaijan’s role in providing access and airspace for Global War on Terror operations was urgently needed. Azerbaijan ended up also sending troops to support U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, further justifying the waivers. Shortly after President Biden ordered the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan in 2021, his administration removed the waiver and re-instated military sanctions on Azerbaijan.

Armenia did not have similar options to deepen military partnerships, upgrade equipment, improve training and planning, or gain operational experience in overseas missions. Yerevan’s patron, Russia, was focused on wars in Syria (2011-2024) and Ukraine (beginning in 2014), and could or would not focus on deterring Azerbaijan or strengthening Armenian defenses. The Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) to which Armenia belonged also failed to render significant aid or support in the first two decades of the current century. Iran remained in Yerevan’s corner diplomatically and strategically, but did not and probably could not provide the types of military assistance, advice, and equipment necessary to improve Armenian military effectiveness. Armenia was less well-served by its alliance network in the years after 1994 than was Azerbaijan, a point which has been increasingly noticed in recent years.

Armenia also suffered economically from the embargo on trade and transit imposed by Ankara during the 1991-1994 war. Opening of trade was the main incentive offered to spur negotiations for the return of occupied Azerbaijani territories, but did not prove sufficiently persuasive. Armenia’s trade in the interwar years was primarily with Iran and Russia, limiting growth and dynamism. Armenia could not keep pace economically or militarily with its re-arming neighbor , and would have to trust in the combination of rugged terrain and the fighting spirit of Artsakh forces in Karabagh and Armenian regular forces elsewhere to tenaciously defend if and when the second round came.

44 Days in 2020

The Azerbaijani campaign of 2020 - dubbed Operation Iron Fist - was a very different affair than the three-year slog in the early 1990s. It began with precision drone strikes that reduced Armenian air defenses and artillery, quickly shifting to combined air and artillery attacks on dug-in defensive positions guarding the roads into the high ground held by entrenched Armenian troops in the seven districts around Karabagh. Azerbaijani forces had developed effective coordination between aerial sensors, electronic warfare systems, loitering munitions, commando units, and ground maneuver forces that methodically blinded, immobilized, and broke the network of defensive positions. Psychological operations using video of strikes on Armenian units and equipment undermined morale in Yerevan and among the Armenian fighting in the field.

A second phase began once the frontline outposts had been reduced and bypassed. Twelve Azerbaijani brigades organized into three corps advanced along two main axes - one encircling Karabagh and the other retaking Azerbaijani districts along the border with Iran (Fizuli, Cebrail, and Zangilan), discomfiting Tehran and greatly complicating the resupply of Armenian forces from that direction. After the southern districts were retaken, Azerbaijani forces turned north and drove on Shusha, a town with great symbolic value and the key to controlling the Lachin corridor into Karabagh.

Once Azerbaijan took Susha and controlled the Lachin corridor the contest was pretty much over for Yerevan and Artsakh. The Russians shot down a helicopter or two to signal that it was time to stop, and a ceasefire emerged that would return the Azerbaijani districts to Baku. That left a precarious fate for Karabagh/Artsakh, which agreed, I believe, to some degree of disarmament but was left under Armenian Administration.

The war came as a shock internationally due to the rapid and decisive military outcome. It was shocking and dismaying especially in Yerevan and Moscow, as optimistic assessments in those places had dominated public discourse leading up to the outbreak of hostilities and fairly long into it. It also began the process of reconceptualizing the entire conflict, frozen since the Bishkek Protocol of 1994 in an unsustainable status quo whereby a smaller, poorer country occupied a portion of and displaced a million citizens of a larger, richer neighbor - which maintained the will and resources to recoup its losses in time.

The Other Shoe Drops (2023)

The 44-day war had decisive and unambiguous results: the rout of Armenian forces from Azerbaijani territories occupied since 1994, the explosion of the myth of military parity between the sides, the revelation that Russia would not actively join the conflict. It created euphoria in Azerbaijan, shock and disillusionment in Armenia. Yet it was an incomplete political result viewed from Baku, for the original casus belli - control of Karabagh - had not been resolved. While the Republic of Armenia’s military forces withdrew from Karabagh, the self-proclaimed Artsakh authorities remained in place, as did their armed units and Russian military observers.

Implementation of the Russian-mediated ceasefire agreement of 2020 made little progress - other than those amplifying Russian control - so Baku decided to launch another offensive to end the political and military existence of Artsakh altogether. The campaign lasted only a day, as Armenian forces faced a hopeless tactical situation and had been weakened by nine months of blockade. It resulted in full Azerbaijani control over Karabagh and the departure of virtually the entire (100,000) Armenian population of Karabagh, prompting charges of intentional ethnic cleansing.

Ending international conflicts via debellatio - total subjugation and erasure of a governing structure - rather than negotiations has troubling implications if globally normalized, especially when coupled with major population movement. The argument carries little weight in Baku, however, given the relatively passive international response to occupation and displacement over the preceding three decades. Remarkably, though, the dissolution of Artsakh coincided with a renewed commitment by Yerevan and Baku to peace: the two sides issued a joint declaration in December 2023 calling for lasting peace, prisoners of war were exchanged between the two sides, and a process for the return of the displaced to both countries was put on the table.

One prominent theory in the study of international relations holds that divergent assessments of relative military strength are a key driver of war - when two sides both think they can win, new or renewed armed conflict is much more likely. The inverse of that theory - when both sides have seen an unequivocal demonstration of one side’s clear military superiority - implies that peace negotiations deemed reasonable to both sides have a better chance of success. That seems to be the situation post-2023 in the South Caucasus. The outcome of fighting in 2020 and 2023 left the door open for conflict resolution that would leave both sides better off than continued tensions on new terms. What was missing was a mediator trusted by both sides, powerful enough to enforce incentives and disincentives in a low-trust dyad, and willing to expend political capital to push for a deal – this is precisely what appeared with President Donald J. Trump’s victory in the November 2024 Presidential election.

TRIPP into the Future - Win/Win (Lose)

While the Trump peace agenda for the South Caucasus took many by surprise as it developed in 2025, supporting components that paved the way for a successful negotiation were put into place over several years. The most central was the development of the “Middle Corridor” concept of shifting China-Europe trade away from Russian territory (the “Northern Corridor”) to Central Asian states as Western sanctions sank in after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. A second was increasing Turkish outreach to Armenia beginning in 2022 based on the logic of economic and political normalization in exchange for a Baku-Yerevan peace deal. A third piece was Armenia’s own launch of a “Crossroads of Peace” initiative in 2023 outlining trade corridors to better connect the region. On January 15th 2025 the Armenia-U.S. Strategic Partnership Charter was signed, providing reassurance for Yerevan and marking a pivot to the West.

The Trump approach to deals and peace through empowered envoys was critical. The envoys’ work started in the case of Gaza negotiations even before inauguration day, and that was likely the case for the Southern Caucasus as well. In any case, Steve Witkoff’s team was on the ground in Yerevan and Baku during the first months of 2025 to work on draft proposals. But real momentum took off with the shuttle diplomacy conducted by Senator Daines.

Additional groundwork was laid through direct bilateral negotiations in Abu Dhabi on July 10th 2025. Diplomats from Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the U.S. worked for several weeks to finalize proposals that included a seven-point joint declaration, a seventeen-point draft peace agreement, and a commercial access and transport proposal referred to as the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP), the Meghri route, or “Zangezur Corridor” (by Azerbaijan). These were jointly endorsed on August 8th at the White House, though details and formal ratification remain far from finalized. Some have likened the set of proposals to the 1970s Camp David accords in creating a prospect for transformational and durable change - and also in bearing significant political risk.

TRIPP calls for a U.S.-led consortium to operate a land route through Armenia’s Syunik province on a 99-year lease. Armenia would get sovereignty guarantees and new transit revenues, while Azerbaijan would get its land link to its exclave Nakhchivan - in the broader sense a link between China and Europe through Central Asia and Türkiye. A quick summary of the potentially transformative effects of TRIPP, if fully realized, would include the following:

- Economics: direct links between Central Asia and Turkiye will strengthen energy throughput and reduce import costs to Europe; expanded rail links will cut delivery times and transport costs for all manner of goods in the region and beyond; infrastructure investments will spur greater east-west trade; foreign direct investment in the South Caucasus will rise significantly and should earn healthy profits for the companies involved. While the initial build-out may cost 3-5 billion U.S. dollars, annual savings in logistic costs could reach 20-30 billion.

- Regional Integration: the TRIPP is relatively short - 32 kilometers - but fills a critical gap in the Middle Corridor conceptual route from China to Europe via the Turkic states and South Caucasus. Armenia becomes a part of regional integration projects for the first time, while Central Asia deepens trade ties flowing West. Far more than China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), TRIPP and the Middle Corridor confer the greatest benefits on local stakeholders - though China stands to profit to a degree as well.

- Diplomatic Relations: the TRIPP and the broader Trump peace agenda reshape the diplomatic landscape of the South Caucasus by providing an economic peace with benefits on all sides - the first non-zero-sum game in the South Caucasus since at least the end of the Soviet Union.

- Geopolitical Benefits: revenues from the new road and rail links, logistics hubs, and trade flows provide serious incentives for cooperation rather than confrontation. This replaces the lose/lose/win paradigm with win/win/lose - the regional stakeholders (and the West) win, with losses accruing only to those who previously held a cynical veto on regional development - Russia and Iran.

If the benefits of TRIPP implementation could be transformative for the region and propitious for the U.S., cui malo (who loses) is also clear - and two regional powerhouses clearly possess firm incentives to disrupt and impede the deal’s implementation. So while it is possible that the corridor opens fairly quickly, creates a virtuous cycle of cooperation, and showcases U.S. strategic foresight and prowess, other possibilities are present, too. Domestic politics or distraction in Washington, or violence on the ground, or continued mistrust might scuttle implementation altogether, or give openings for Moscow or Beijing to steer the course of events. Or the TRIPP and Middle Corridor could grow in complexity as a sort of condominium among competing powers and routes, with local actors balancing various investors and external patrons in an evolving transit market rather than a stable American-guided project. Much depends on Washington’s attention span and follow-through, and perhaps even more depends upon the actions of the plan’s opponents.

Who Could be Against?

Russia, Iran and other regional players have varying degrees of discomfort with the TRIPP. For Russia and Iran, the TRIPP bypasses their preferred trade routes and undercuts prospects for their North South Transport Corridor linking Russia to the Indian Ocean. Tehran has long opposed strengthening links among the Turkic states, would lose its current transit leverage over the South Caucasus, and would now face increased U.S. (perhaps Israeli) presence along its northern border. Russia, in particular, faces a loss of influence in its strategic backyard if U.S. and Turkish corporate and official presence in the Caucasus grows, and fears a grave reputational loss that will stimulate pan-Turkic solidarity across a broad geography. India and China might have their own concerns about growing cooperation among regional majority-Muslim states, as the evolution of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) into a serious force in Eurasian geopolitics may complicate their regional strategies. TRIPP has the potential to significantly expand the speed and scope of the Middle Corridor, enlivening the OTS as a byproduct.

For China, the new impetus given by President Trump to the TRIPP, regional peace, and expanding trade along the Middle Corridor presents something of a dilemma; rising east-west trade could benefit Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but under local rather than Chinese management. And if the U.S. does what China traditionally tries to do itself - parlay commercial access into subtle political control - this may work against Chinese interests. Beijing seems to have decided that it’s better to join rather than resist the Middle Corridor as its momentum builds, and thus recently joined the Middle Corridor Multimodal venture initiated by Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Georgia. Xi probably sees no reason to dampen Trump’s enthusiasm at this point, trusting in its own long-term ability to direct and control the Middle Corridor - while leaving direct struggle against U.S. influence to the Russians.

Armenians within the country and in the politically formidable diaspora also have reason to be wary of a set of agreements they believe locks them into perpetual strategic disadvantage. As the International Crisis Group notes, approval of the peace agreements will entail the Armenian government “asking voters to, in effect, ratify their own defeat at a time when the trauma from losses in 2020 and 2023 is still fresh. Compounding voters’ frustration is a sense that Azerbaijan keeps besting Armenia at the negotiating table but gives little in return.” Some in Yerevan fear decreased control over the strategic border with Iran, while the majority of the Armenian public and a significant portion of the parliament oppose the deal. There are entrenched views in Yerevan that Russia remains the eternal guarantor of Armenia’s security, Turkiye and Azerbaijan the eternal enemy, and that “new thinking” is delusional. Much of the Armenian diaspora vigorously opposes Prime Minister Pashinyan, considering him a disaster or a traitor, while the primary Armenian-American political organization has commenced work to slow or end implementation of the deal in the runup to U.S. midterm elections in 2026.

As Ilan Berman of the American Foreign Policy Council has noted, Armenia basically faces “an information war on three fronts” at present: from Russia, Iran, and from its own diaspora.

Pashinyan in the Eye of the Storm

Transformation of the South Caucasus from a fractured conflict zone to a prosperous one will only succeed if Pashinyan has the support of both Trump and Aliyev in navigating the obstacles posed by these various opponents. Garo Paylan, an ethnic Armenian political analyst from Türkiye and former member of the Turkish parliament, has implored the U.S. Congress to press for continued American engagement to sustain momentum for the joint efforts. In Aliyev’s case, wisdom means matching Pashinyan’s steps towards normalization without undue rhetoric on the Armenian constitutional referendum to remove language implying revanchist territorial claims.

Long-time observer of the South Caucasus conflict Thomas de Waal has laid out the complex cognitive task Pashinyan is undertaking: to shift the discourse in Armenia and in the diaspora from “historical Armenia” to “real Armenia,” with attendant adjustments to rhetoric, negotiating positions, and practical arrangements with Baku and Ankara. The shift is not just a dialogue evolving between Pashinyan, the Armenian electorate, and his opposition; it is now an international contest involving Moscow-aligned Armenian politicians and the Tucker Carlson wing of the MAGA movement, each working to cast Pashinyan as a devil of the anti-nationalist or anti-Christian variety.

Some of Pashinyan’s statements have been quite forward-leaning in terms of peace advocacy, and deserve greater attention in the West. To wit, his remarks during an October 31st presser:

- “We must free ourselves from the worldview that was shaped for us by KGB agents.”

- “When we say, ‘A Turk never changes,’ they say the same about Armenians. When we say, ‘How can we trust Azerbaijan,’ they say the same about Armenians.”

- “When we say ‘we have learned nothing from history,’ they respond: ‘you’ve learned nothing from history if you want peace with Armenians.’”

- “The stereotypes Armenians have about Azerbaijanis, and those Azerbaijanis have about Armenians, are mirror images of each other.”

His statements are remarkable in at least three ways. First, political leaders facing nationalist backlash seek to buttress their own nationalist credentials - rather than turning the tables on the accusers by pointing out how their rhetoric and positions practically damage the nation. Second, conciliatory statements across the Christian-Muslim divide in the South Caucasus are rare if not unprecedented. Third, Pashinyan’s early positions as Prime Minister did not indicate great flexibility on issues of Karabagh and peace with Azerbaijan. In 2018 he argued that Azerbaijan was upsetting prospects for peace through its rearmament program, and he fully backed the legitimacy and armed readiness of Artsakh. By 2025 he assessed that it was a mistake not to recognize the legitimacy of Azerbaijan’s sovereignty over Karabagh earlier, which may have left room for a negotiated settlement.

Pashinyan’s stance on peacemaking may be politically clever, given that many Armenians blamed him for military defeat and shifting the frame undercut arguments that continued war footing was sustainable in the first place. Yet it may also have important and constructive long-term effects. Reconciliation in long-running conflicts - such as in the western Balkans - has proven to be a long, drawn-out process that requires a significant degree of reframing and reconceptualization. Decades after formal peace agreements, the work of thinking about neighbors/former adversaries remains a challenge, but with consistent effort, can gain traction. Whether it is motivated by principle or political survival, Pashinyan’s intellectual effort has value for the region at large, and certainly for U.S. interests.

Trump’s Personalized Diplomacy as Double-Edged Sword

Donald J. Trump has brought an energy and agility to U.S. foreign policy making because of his disdain for institutional processes he believes have led to serial failure since the end of the Cold War - the phenomenon of “the swamp” applied to international affairs. By employing transactional negotiations, direct pressure and strategic leverage in the unapologetic service of the national interest, he has moved the needle on negotiations over trade, NATO member defense spending, and seemingly intractable conflicts. Central to his method has been the deployment of empowered special envoys and a small circle of White House advisors to interpret and operationalize his policy instincts, which have generally been rooted in realpolitik - and a savvy eye for regional context. Formal policy structures and processes at the Departments of State and Defense and National Security Council have been chasing and then carrying out policy rather than shaping and informing it, and this is by design.

Yet the price of a highly personalized and centralized policy process is paid in the stages of implementation and follow-through. Bandwidth limitations and span of control challenges mean that topline agreements requiring significant subsequent planning, coordination, compromise, and adjustment may take long months or years to come to fruition - leaving room for hedging and subversion by antagonistic actors, or loss of confidence by key stakeholders. It would be premature in the first year of an administration to declare this a record of “bold promises, unmet goals,” but there is a real risk that by the midterm elections that charge will stick.

The Trump Administration has intentionally slashed the size and duties of the National Security Council and the State Department, typically the drivers of interagency processes designed to follow through on foreign policy decisions and commitments. Combined with the fact that the administration has nominated less than half of the roughly 800 key appointed policy positions that require Senate confirmation, and had fewer actually confirmed, this means that the number of hands and minds dedicated to implementing policy breakthroughs or working through the additional refinements is insufficient. And with a contentious 2026 midterm election campaign already drawing the President’s attention, foreign policy concerns seem likely to recede on his agenda.

For the South Caucasus, this means that the unique set of circumstances that led to a peace opening in 2025 - an interested U.S. President, empowered envoys, reduced bureaucratic process, regional actors loathe to openly oppose Trump, and his personally high risk tolerance - may not look the same in 2026. The power of the personalized process wanes when the person is not fully engaged in the same way. With his name attached to the centerpiece of the peace agenda - TRIPP - this may be one that remains a priority for a second year, but there are no guarantees in such matters.

Back to Lose/Lose?

It is better to have not only an opening but an initial agreement than not to have them, even with details and ratification. The tantalizing possibility of shifting the South Caucasus from a lose/lose reality for the primary actors that results in a win for anti-Western revisionist powers towards a win/win that benefits the West and sidelines Moscow and Tehran merits continued attention and sustained effort from Washington. The circle of beneficiaries is wide enough to assure that the costs will not fall entirely on the U.S.

There are three ways the current momentum can be derailed. The first is that, having declared the solution complete, the Trump Administration takes the proverbial foot off the accelerator pedal and fails to catalyze the commercial deals and security arrangements necessary to keep the TRIPP on schedule. Commercial logic works, but nothing upends commercial logic like political uncertainty and security threats. Process must be ostentatiously maintained through both official meetings and private sector deal-making, both accompanied by positive press. Otherwise we could find ourselves in a new Minsk Group scenario of kind words, deteriorating trust, and escalating rearmament. Absence of clear and direct U.S. leadership would certainly re-open the door for others to set the pace and direction of new arrangements - Moscow for diplomacy and security, Beijing for commerce, and Tehran for mischief.

The second key risk pertains to the person of Nikol Pashinyan. If he is removed from the equation either through electoral loss in the June 2026 elections or through more direct means by his enemies, Washington (and the entire peace process) will have a serious interlocutor problem. Absent Pashinyan, it is unclear that any Armenian leader could successfully argue for taking the hard steps to peace. Those familiar with the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 and the paralyzing effect it had on the Israel-Palestine peace process can imagine what a reprise in the Armenia-Azerbaijan context would have, and the overheated rhetoric regarding Pashinyan gives reason to contemplate the scenario. In the less dramatic eventuality of electoral loss, Armenia may return to the logic of reliance on external forces to pressure Azerbaijan rather than pursuing constructive arrangements for regional cooperation.

The third possible point of failure stems from Russia’s incentive to undermine or co-opt implementation. Russia has several cards to play to contest or subtly control TRIPP and the regional peace process. One is the fact that Armenian railroads are operated as a subsidiary of the Russian state-owned rail corporation. A second is that Russia maintains significant military forces in Armenia, and an airbase that can be used for further reinforcement at any time. Russia operates a nuclear reactor at Metsamor that produces up to 40% of Armenia’s electricity supply. Beyond the borders of Armenia, Russia controls 85% of the water flow into the Caspian Sea, and has shown a penchant for manipulating the flow of the Volga River for demonstrative purposes. Iran has more modest options for opposing or subverting TRIPP and the regional reorientation towards the West, but Moscow’s cards are fairly potent.

These risks all boil down to a common logic: the low-trust, highly-securitized status quo that preserves Iranian and Russian influence will continue unless a highly contingent process with multiple potential points of failure succeeds. Economic opportunities, war-weariness, initialed diplomatic deals and geopolitical logics notwithstanding, it can still be easier to stand pat than to move in a new direction. If that happens, the South Caucasus will pull back from the brink of win/win/lose and slip back into the decades-long morass of lose/lose/win - and the regional benefits for Central Asia and the West will go unrealized.

Policy Advice

The countries of the region have taken great pains to signal to Russia and Iran that their interest in reconciliation, including the TRIPP, a finalized peace deal, and expansion of the Middle Corridor, does not mean categorical rejection of ties to the northern and southern neighbors. The term “multi-vectoral policy” is heard frequently in the region, meaning the avoidance of bloc behavior and pursuit of positive ties with competing patrons.

The best advice for Washington - in addition to pressing for continued implementation momentum as discussed above - is to adopt the spirit of multi-vectoral policy to make the TRIPP and associated developments as broadly palatable as possible. Don’t exclude Chinese, Russian, or Iranian cargoes or companies (except those in sanctioned categories of trade). Don’t press the U.S.-led consortium as the vanguard of a commercial invasion designed to exclude the companies of other nations. Adopt and amplify steps that complement TRIPP but don’t originate in Washington - such as the recent announcement from Ankara of intent to reopen the border with Armenia within six months. Don’t insist that the TRIPP and Middle Corridor cannot coexist with other corridors, such as the International North South Transit Corridor, Iran’s Aras Corridor, or the BRI; in matters of trade routes, more is better. Emphasizing the complementarities of the new route, and its availability even to quasi-antagonists, will strengthen its chances for success.

Another smart move for the Trump Administration (as well as Armenia and Azerbaijan) would be not to exclude Georgia from infrastructure developments that are aimed at regional transformation. The anti-Western turn taken by the Georgian Dream government under Bidzina Ivanishvili has been self-destructive and irritating, but the whole point of the TRIPP is transformative leveraging of geopolitical advantage through geoeconomic logic. There is no reason to think that Georgia would be immune to such logic, and incentives of investment and profit will strengthen the still-robust pro-Western elements within Georgia. As a Member of the European Parliament, Romanian Cristian Terhes, recently wrote:

Just as economic cooperation helped achieve mutual respect and lasting peace in post-war Western Europe, strengthened interconnectivity can support lasting stability in the South Caucasus. The existing interconnectivity between Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, as part of the Middle Corridor, already demonstrates the region’s potential. Including Armenia in this corridor via the TRIPP project could further strengthen regional stability, with significant benefits for the Armenian people, but its success depends on resolving highly sensitive political, constitutional, legal, and security issues, which will require public support, political will, and close attention to detail.”

Above all else, Washington cannot let Nikol Pashinyan appear to be a lone voice shouting in the wilderness to Armenian voters - and to the Armenian diaspora in the U.S. Making the case for peace and prosperity on their merits should be sufficient, but given the bitter recent history of the region, and the justifiably high level of concern among Armenians about the risks involved, additional levels of reassurance are warranted. If Pashinyan stays in his seat and wins a mandate on the referendum for constitutional reform, the momentum towards fulfillment of the Trump project for the South Caucasus will be serious and perhaps unstoppable. Until that comes to pass, though, formidable obstacles and opponents give reason to think the cynical old paradigm just might survive.