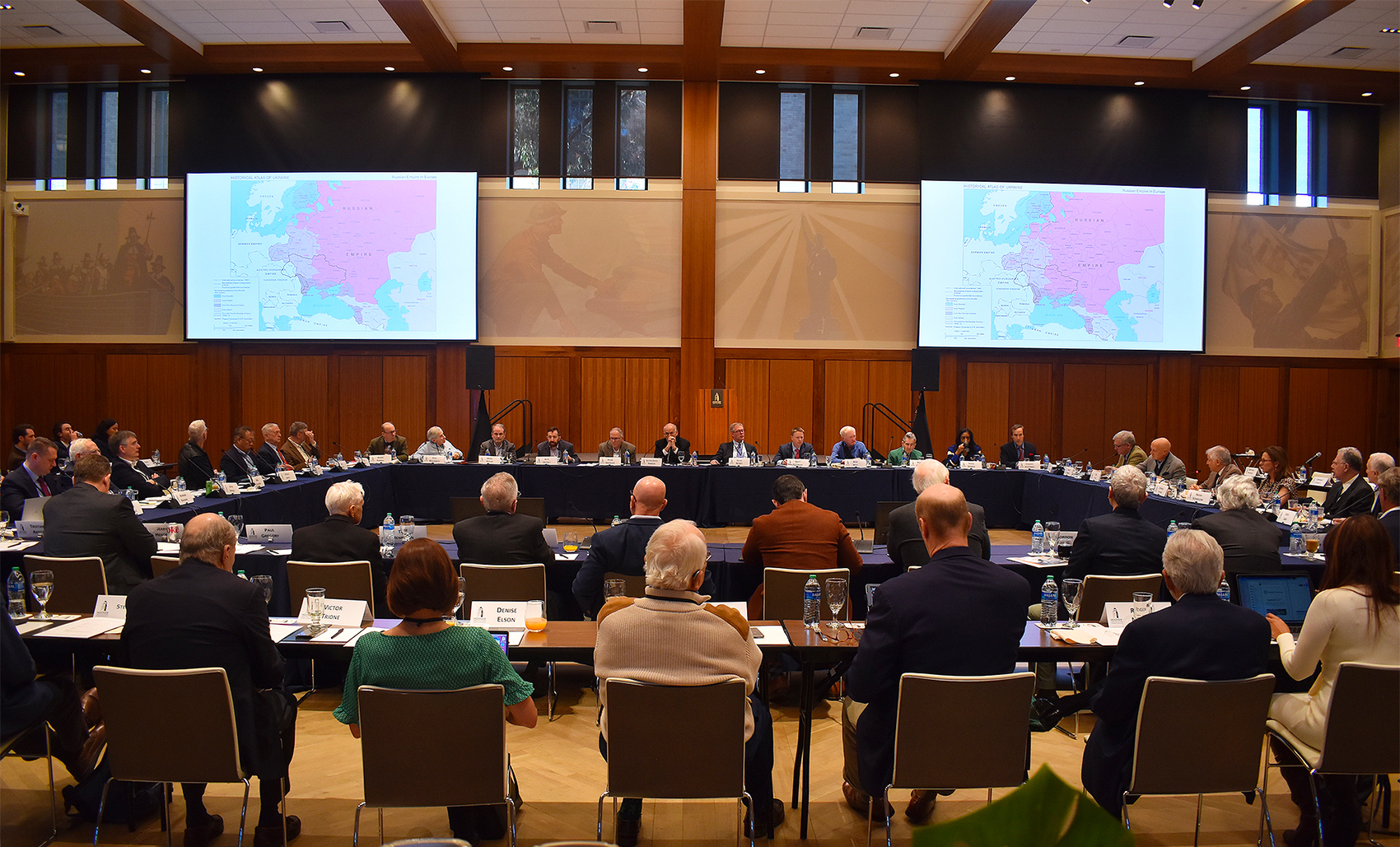

Hoover Institution (Stanford, CA) – The Hoover Institution’s Military History in Contemporary Conflict Working Group hosted a workshop on Friday, March 17, in which scholars explored the causes of the Ukraine War, assessed the current conditions of Ukrainian and Russian forces, and examined potential outcomes of the war, including the prospects for a peaceful settlement.

Convened by the working group’s chair, Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow Victor Davis Hanson, and organized by research fellow David Berkey and program assistant Megan Ring, the conference featured three presentations: “The Historical Relationship between Russia and Ukraine,” by Kleinheinz Fellow Stephen Kotkin; “How Could Ukraine Achieve a Military Victory?” by Center for Naval Analyses director of Russian studies Michael Kofman; and “The Prospects for Peace in Ukraine: Is a Negotiated Settlement Possible?” by Milbank Family Senior Fellow Niall Ferguson. The day concluded with a general discussion among presenters and other attendees.

The Historical Relationship Between Russia and Ukraine

Kotkin explained that Russian President Vladimir Putin, in his desire to return Russia to its former imperial glory, has ultimately undermined his own objectives by his hasty decision to invade Ukraine. Following Russia’s invasion on February 24, 2022, Ukraine has only strengthened its identity as a separate and distinct nation from Russia, Kotkin said.

Ironically, Putin’s decisions have continued a trend that played out under Russian leaders with whom the current president shares a similar mindset: Mikhail Kutuzov, the nineteenth-century military leader who defeated Napoleon Bonaparte in 1812, and Joseph Stalin, the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953.

Putin, Kotkin explained, shares Kutuzov’s vision of a Russia that is multiethnic in character. For Kutuzov and Putin alike, the people who live in Russia proper are “Greater Russians,” Belarusians are “White Russians,” and the Ukrainians are “Little Russians.” During the era in which Kutuzov lived, a Ukraine with politically recognized borders did not exist. Moreover, at the time, the Crimean Peninsula was the domain of the Tatars, an ethnic Muslim population that had been under the rule of the Ottoman Empire until Empress Catherine the Great transferred this territory to Russian control in 1783.

Despite Kutuzov and Imperial Russia’s victory over Napoleon, a nationalistic culture prevailed over the concept of imperialism in lands dominated by the Kremlin, especially in Ukraine.

Kotkin described how Stalin further consolidated the Ukrainian nation. First, at the tenth Party Congress in 1921, Stalin recognized Ukraine as an independent nation. Second, a year after the congress, Stalin expanded the size of Ukraine to include the Donbas region. And third, Stalin or one of his functionaries agreed to transfer Crimea to Ukraine before his death in 1953.

Before becoming Soviet general secretary in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev was the communist party boss in Ukraine. To consolidate the support of his former constituents, he made the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine official in 1954. Although the Ukrainian state, on paper, had the authority to govern its internal affairs, it was Ukraine’s party leader, a direct subordinate to Moscow, not the state’s president, who in practice wielded political power.

Kotkin asserted that Ukrainian national identity had been further consolidated by Putin’s actions in the past eight years, in particular his support of separatists in Donbas, the annexation of Crimea, and the “special military operation” that began on February 24, 2022.

Kotkin also explained that Russia’s leaders have historically viewed their nation as a providential power with a distinct civilization and a special mission in the world. However, the Russian state’s capabilities have continually failed to meet its aspirations and Russia has invariably devolved into personalist rule. This was the case in Russia’s quest to become a great power equal to the West following the Second World War. Russia won that war, Kotkin said, but lost the peace. The Kremlin’s attempt to use state power to build a modern nation failed. Inevitably, the gap between the USSR and its Cold War adversaries widened economically and militarily and thus led to the Soviet Union’s ultimate collapse in 1991.

Kotkin argued that some analysts are mistaken to believe that NATO expansion caused Russia to feel insecure and thus was the primary reason for Putin to start a war in Ukraine. As Kotkin explained above, Putin, like Kutuzov and other Russian imperialists, doesn’t believe Ukraine exists as a separate nation and is largely motivated by an impulse to make Russia a great power.

Kotkin said that Western-led sanctions and military support, as well as harsh rhetoric against Russia, have provided Putin fodder to demonize his adversaries and consolidate support among the Russian people. Moreover, he explained that the Kremlin has been able to bypass sanctions on gas and oil by selling oil through brokers in global energy markets.

As an alternative to what he called a “sanctions and Centcom approach,” Kotkin proposed that the West explore creative ways in which diplomacy can be wielded to end the war and space can be created between the Kremlin and the Russian people.

How Could Ukraine Achieve a Military Victory?

In his presentation, Michael Kofman provided a detailed timeline of the war, evaluated the conditions of Russian and Ukrainian forces (including levels of manpower, equipment, and ammunitions resources), and considered how Ukraine could achieve a favorable military outcome in the war.

Kofman said that during the initial invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian forces had been structured on the premise that they could rapidly institute regime change. He said that Russian forces failed to meet this objective for various reasons.

The Kremlin had planned for an initial phase of ten to fourteen days of fighting. Russian forces invaded Ukraine with a hollowed-out force, hoping that the Russian FSB (security forces) could take over key cities and ultimately the capital, Kyiv. They weren’t expecting a sustained combat operation against Ukrainian forces.

Kofman said that the modern Russian military leadership had come to believe potential adversaries didn’t have the force density to hold static fronts. They thus designed their forces on the basis that air defense and assaults constituted the most important aspects of a military operation. Since 2008, they made a series of reforms directed toward partial mobilization, meaning that significant portions of their total force constitution would not be active-duty personnel. Kofman explained that Russia figured it could balance this manpower deficit through contractors instead of raising the size of its active-duty force. Russia’s military leadership made further compromises by cutting the size of its infantry at the squad, company, and battalion levels.

As a result, Russia’s total military readiness was only at 70 percent by the time of the invasion. Kofman maintained that in this current war, successful combined arms operations are greatly dependent on a respectably sized infantry, without which it is impossible to hold and capture cities and terrain.

Unlike senior officers, Russian ground troops were not aware of the invasion until twenty-four to seventy-two hours in advance. This level of secrecy greatly hampered Russian forces’ ability to prepare and organize for a large-scale invasion of a sort that they hadn’t made in over forty years.

Moreover, the Ukrainians’ will to fight proved essential in the early part of the war. Retired officers and other Ukrainian volunteers’ willingness to defend Kyiv bought time for the government to deploy additional personnel who could position themselves to slow down the advance of Russian forces.

In summer 2022, Kofman explained, Russia tried to reconstitute its forces and place greater focus on taking control of Donbas. Facing heavy losses of infantry and challenges in retaining manpower, Russia mobilized separatist forces from the Donetsk oblast and personnel supplied by a private military contractor, the Wagner Group. To compensate for the deficit of manpower, Russia also began to rely on the use of heavy artillery in the battlefield.

Despite their significant losses, Russian forces had been grinding down the Ukrainian army in this war of attrition. In Kofman’s view, in the early summer the Ukrainian army had been in desperate straits until the United States and West provided materiel and intelligence support. He said that without such support, this war may have followed a similar arc of the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939–40, in which the Soviets suffered severe losses, but were nevertheless able to force Finland to surrender a portion of its territory.

By September 2022, Ukraine had recaptured and forced Russian withdrawal in key cities, including the strategically important Kherson, located on the west bank of the Dnipro River near the Black Sea.

By winter 2022, Ukrainians were increasingly optimistic about shaping battlefield outcomes and winning the war. However, at that point, both sides of the conflict experienced challenges with manpower and artillery.

In January 2023, Russia was focused on recapturing territory it lost earlier in the war. As Russian forces reconstituted themselves through the partial mobilization program of 300,000 additional troops the Kremlin had announced the previous September, it compensated for its deficit in military readiness by deploying trained convicts under the leadership of the Wagner Group.

The Kremlin deployed Wagner to recapture the city of Bakhmut where Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky was determined to halt Russian advances in Donetsk. Through heavy use of artillery—and indiscriminate use of this firepower—Wagner was able to overwhelm and ultimately surround Ukrainian forces by February.

Currently, Russian forces now find themselves in a condition that is the reverse of the beginning of the war, Kofman maintained. In February 2022, Russia was limited in personnel and possessed large amounts of munitions. Today, its force size is larger, but it is limited in munitions. Russia is also limited in its offensive potential, and it has been defending gradually smaller swaths of territory.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian forces haven’t fared much better. They too have been running low on munitions and have experienced significant losses in personnel (especially of their most experienced and most competent forces).

Kofman said that the next four to six months of the war will be decisive. An outcome that is favorable to the Ukrainians depends on continued military support from the United States and Western allies. Kofman cautioned, however, that a decisive military victory for Ukraine won’t necessarily end the war and Putin’s will to continue fighting. The only conditions, he explained, on which a path to peace can be charted is if both sides believe they can’t achieve their objectives by force; one or both sides minimize their war aims; and at least one side realizes that it can’t sustain the war for military, political, or economic reasons.

A US Strategy for Ukraine

Fouad and Michelle Ajami Senior Fellow H. R. McMaster gave brief remarks following Kofman’s presentation, arguing that the United States has lacked a strategy and purpose in its support of Ukraine. He said that there has been a recent tendency in Washington to execute wars incrementally and without the objective of trying to win them. To win a war, he said, one side needs to convince the other that it has been defeated.

McMaster asserted that there are four components of this objective: (1) the Russian military needs to be defeated on the battlefield; (2) Ukraine’s territory needs to be restored to pre-2014 or pre-2022 borders; (3) the Ukrainian economy needs to be rebuilt; and (4) Ukraine’s armed forces need to be capable of deterring and defeating future forms of Russian aggression.

To meet this objective, McMaster said that the United States and allies should continue to provide Ukraine with support in the form of sustained sanctions that constrain Russia’s ability to finance and wage war and enable the Ukrainian military to develop the competencies for combined operations to overwhelm their adversary on the battlefield.

Is a Negotiated Settlement Possible?

In his afternoon presentation, Niall Ferguson explained that President Joe Biden’s unexpected visit to Kyiv in February, when he pledged unwavering support to Ukraine “for as long as it takes” in its fight against Russia, was an extraordinary act in the history of foreign policy. Ferguson said that President Biden went far beyond President John F. Kennedy’s speech at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate in June 1963, in which he expressed solidarity with that city against the looming threat of communism.

Echoing a January 2023 op-ed in the Washington Post written by former national security officials Condoleezza Rice and Robert Gates, Ferguson said that “time is not on Ukraine’s side.”

Ukraine is locked in a grinding conflict with a larger power that can sustain a war effort for an indefinite period because of its authoritarian model of governance and the superior resources at its disposal. Meanwhile, Ukrainian success on the battlefield is heavily reliant on support from the United States, where the health of the economy, not the fate of Ukraine, is the primary concern of voters. American public support for providing military assistance has significantly dropped over the past year, and some Republicans, he said, are losing their conviction that the issues in this conflict represent a legitimate American national security interest.

The West, Ferguson argued, also underestimates China’s commitment to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Chinese exports have helped keep Russia’s economy alive. China also has benefited from discounted Russian oil and gas.

The primary reason that China’s President Xi Jinping is heavily invested in Russia’s assault on Ukraine is because he would rather see American resources being expended in Eastern Europe than in the defense of Taiwan, which Xi has unquenched ambitions to unite with the mainland.

The United States has adopted the position that it cannot afford for Ukraine to lose. China has adopted a similar position regarding Russia. This could be quite problematic, Ferguson explained, because these positions risk the possibility of China responding with weapons transfers to Russia, thus escalating the conflict.

Ferguson concluded that a negotiated settlement over Ukraine is still likely, but it will take time. It will only occur once both the United States and China realize it is in their interests to stop supporting the conflict.

According to data Ferguson presented, wars are relatively easy to end within their first year. However, once a war reaches the one-year mark, achieving peace becomes increasingly difficult. The reason is the parties want to exact revenge on each other once their respective body counts reach a certain threshold.

Based on his historical observations, Ferguson said he believes that it will take approximately two years for peace negotiations to lead to a settlement. The challenge, he explained, is that the negotiations have not yet begun.

Suggested Reading

“The War in Ukraine Today and Yesterday.” Stephen Kotkin. The Washington Free Beacon. February 18, 2023.

“The Cold War Never Ended.” Stephen Kotkin. Foreign Affairs. April 26, 2022.

“Not Built for Purpose: The Russian Military’s Ill-Fated Force Design.” Michael Kofman and Rob Lee. War on the Rocks. June 2, 2022.

"All is Not Quiet on the Eastern Front.” Niall Ferguson. Bloomberg. December 31, 2022.

“Time is Not on Ukraine’s Side.” Condoleezza Rice and Robert Gates. Washington Post. January 7, 2023.