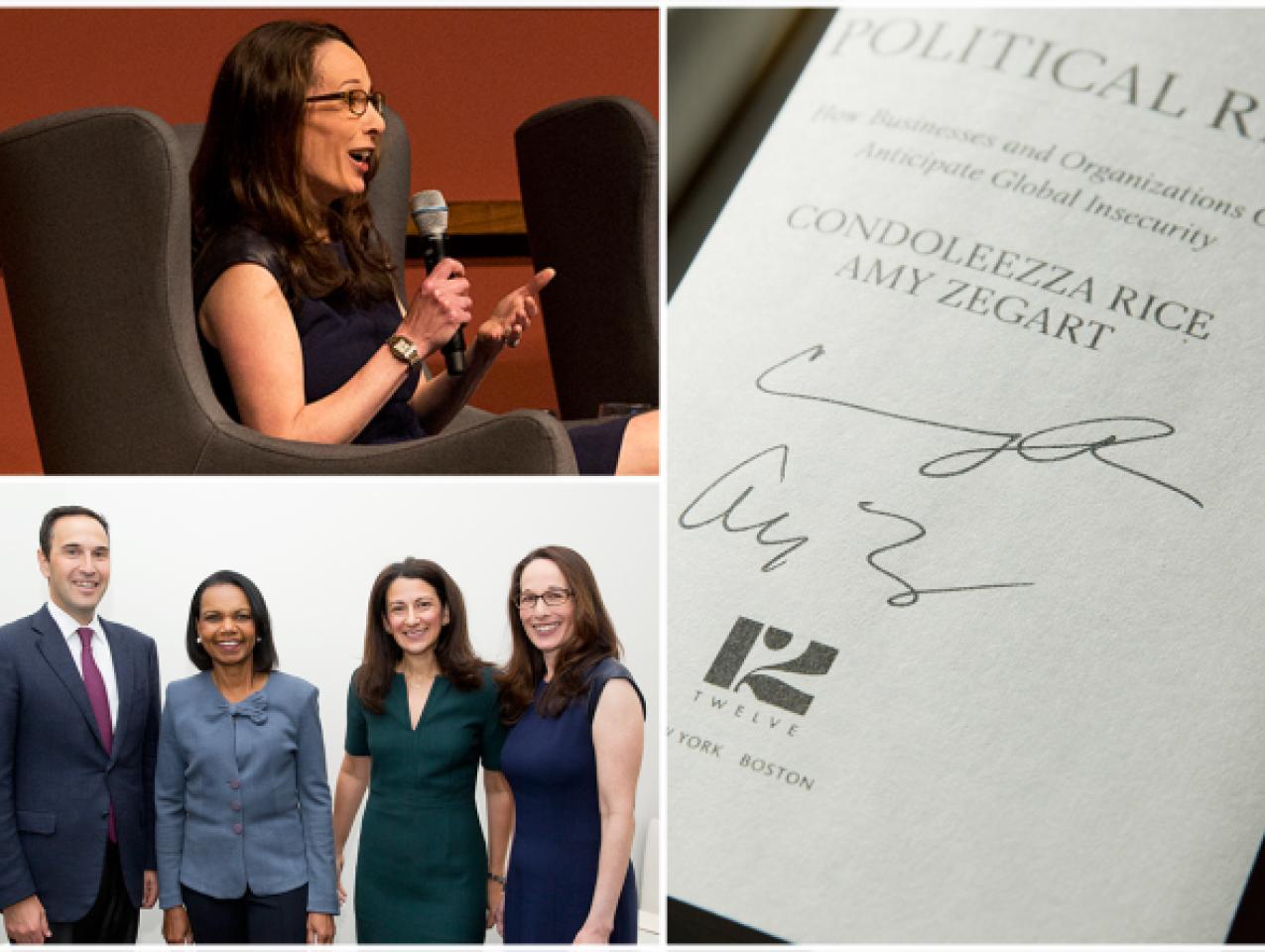

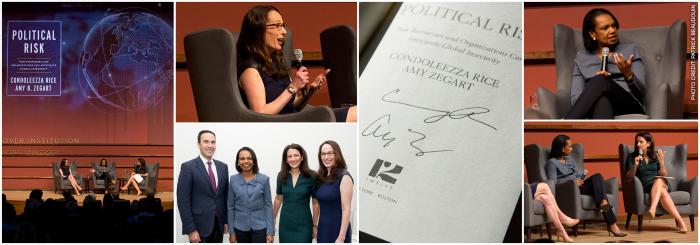

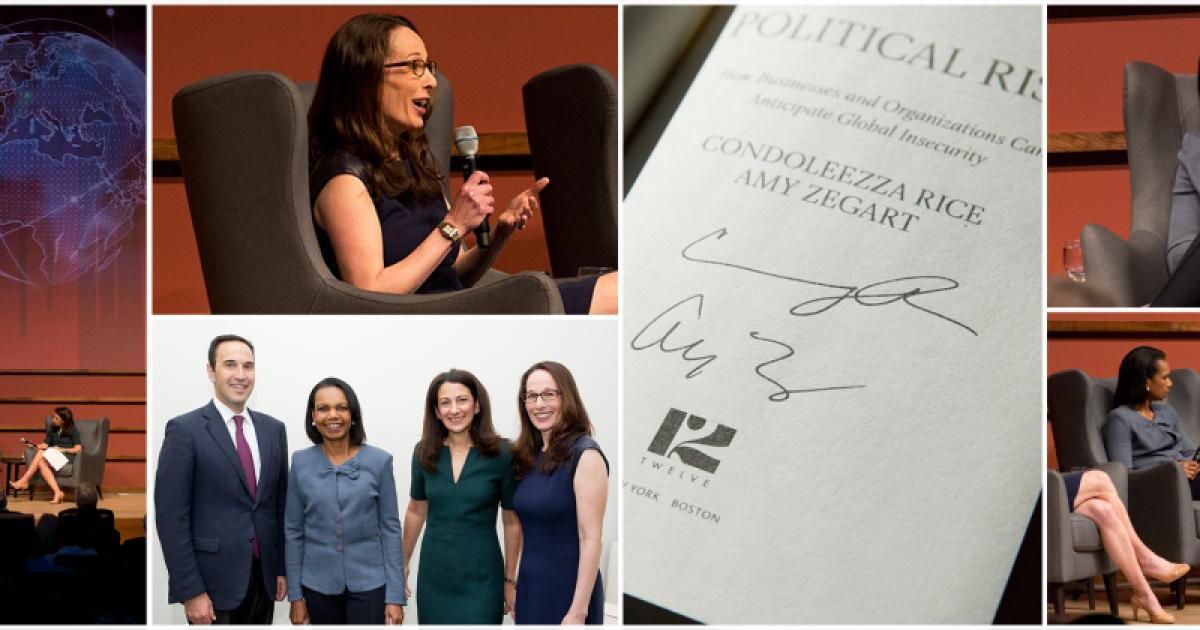

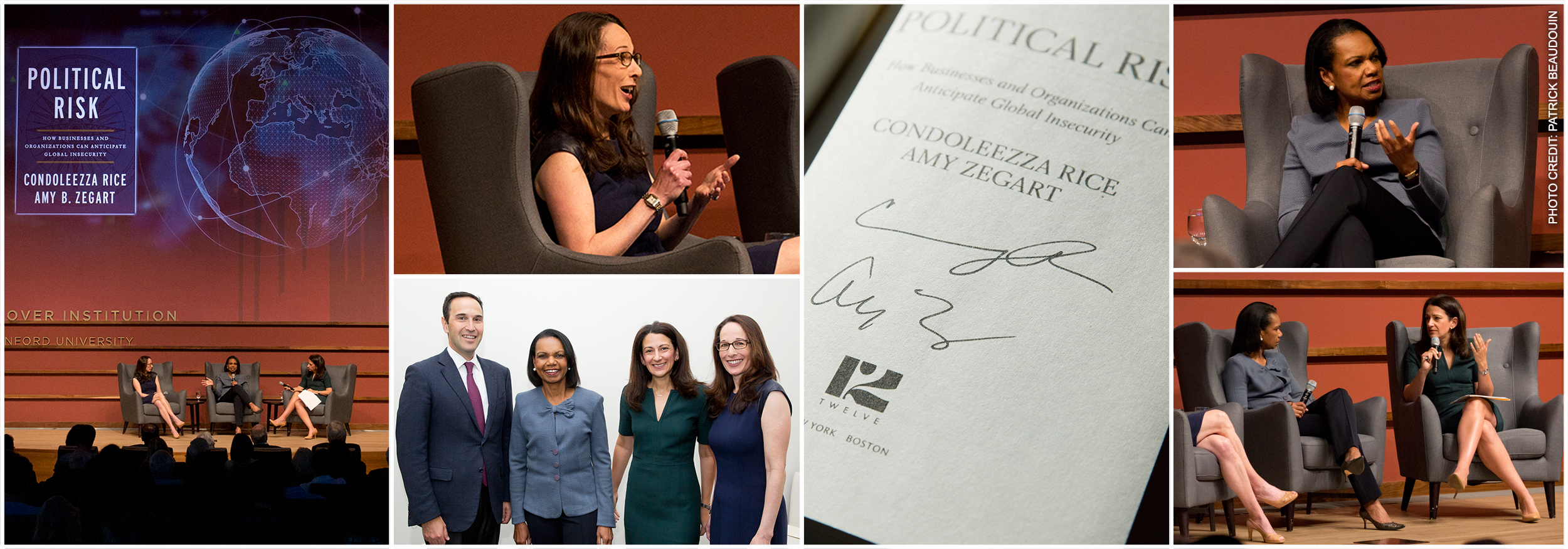

Stanford political scientists Condoleezza Rice and Amy Zegart offered insights on “political risk” in an unstable world at the Hoover Institution on May 11.

Rice is the Thomas and Barbara Stephenson Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a former US secretary of state. Zegart is the Davies Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and co-director of Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

They co-taught the Stanford MBA course, “Managing Global Political Risk,” to more than 200 students over the past six years, collecting research for their course and recently published book, Political Risk: How Businesses and Organizations Can Anticipate Global Insecurity.

Janine Zacharia, a former international affairs reporter for the Washington Post and visiting lecturer at Stanford’s Department of Communication, moderated the book discussion program, which included questions from the audience in Hoover’s Hauck Auditorium.

Rice said that political risks increase in uncertain environments, such as changing global politics, accelerating technology, and emerging activist issues. Altogether, “It makes it extremely difficult to know where risk is coming from,” she said.

As Rice explained, so-called “black swan events” actually could be foreseen if preparations were taken, Rice added. A black swan event describes an unanticipated incident that has a major effect on a society.

For example, on September 11, 2001, when the United States was struck with devastating terrorist attacks, it was imperative that the US government get the message out to their embassies and foreign governments that the American leadership was not “decapitated” and was still functioning. They did so, because as the US Secretary of State, Rice had trained for this possibility.

Yet often the problem is that risk managers are like the “skunk at the picnic,” because they don’t seem at first to represent “value” to a company’s bottom line, Rice said. But when the unexpected threat happens, their importance is quickly realized, as in the case of cyberattacks.

Just like playing baseball is difficult, Zegart noted, the same is true for risk management. It takes practice, preparation, and foresight. “Most companies don’t do it as well as they should,” she added.

Psychology research shows that people tend to be overly optimistic about handling situations, Zegart said. Surveys show that sports fans, even when paid to accurately rate their team’s chances of winning, tend to over-predict wins for their favorite teams.” This constitutes “optimism bias,” as Rice called it.

Changing Global Politics

When asked about recent elections in other countries where populists won, Rice said that the world order—with its free markets, free trade, and norms—is entering a new environment. “We take for granted the premise on which the international liberal order was built.”

In populism’s rise, people think they have found leaders who will do their bidding on issues like trade, she said. “I think the ground is shifting.”

And so, this constitutes even more political risk for governments and companies that do not know how to handle the shifting political dynamics, she said.

Rice described China as an interesting case, due to recent trade issues under the Trump Administration. China, poised to leapfrog the United States in artificial intelligence and other innovation fields, now poses national security implications when they try to buy American firms. As a result, a groundswell of opposition has been building to such trade dynamics.

“It’s not Donald Trump, not a single person or administration,” said Rice noting that he is reflecting “big macro-trends,” such as isolationism and protectionism, that are prevalent in this country and others.

While Rice said she did not support the original Iran nuclear deal— there were problems with it— she likely would have stayed in it. However, the Trump administration deliberated and took feedback on the agreement for more than a year, yet fixes to the problems have not emerged. Rice has been quoted as saying breaking it “won’t be the end of the world.”

On the North Korea talks, Rice said, “I do think they set the table pretty well for this negotiation,” because Trump had a card to play that no prior president had.

She explained that once North Korea showed it was dangerously close to having the capability to hit the United States with a nuclear missile, the world understood that this was something no US president could tolerate. She also gives credit to North Korea’s Kim Jong Un for being “clever.”

“It’s possible that this is a new playbook,” Rice said. She said the North Korean leader has a serious dislike of the Chinese and that his strategy might be to move away from them and toward the South Koreans and Americans through these nuclear talks planned for mid-June.

‘Different Risk Appetites’

Rice said that “Different risk appetites emerge in different industries.” While a gas and oil company that operates in remote countries might be more willing to confront risks, one that deals daily in customer retail or services might not. Zegart points to the case of SeaWorld as an example.

In 2013, SeaWorld had just completed an initial public offering that exceeded expectations, raising more than $700 million in capital and valuing the company at $2.5 billion, according to Zegart.

Eighteen months later, SeaWorld’s fairy tale had become a nightmare. The stock price had plunged sixty percent and top management resigned. The reason was due to a low-budget documentary film that featured how SeaWorld’s famed killer whales were mistreated while in captivity. Amid the widespread public and governmental backlash, SeaWorld’s stock fell from $38.92 a share to $15.77 in 2014— and it has still not recovered.

Regarding Facebook and its privacy of data issues, Zegart said the company is in a very different situation than it was a year or two ago. Yet it is unclear if Facebook president Mark Zuckerberg has trusted “truth sayers” around him. People have to look for political risks to see them, she said.

Rice advised company CEOs to be very careful with their words on social media. “Multiple audiences will hear you differently,” she said. It is a smart idea to have someone review a tweet before it is distributed.

Both Rice and Zegart touted the learning capabilities of organizations like football teams. They relentlessly examine their plays, make changes, practice, and look for solutions to problems. The pressure to win in professional sports encourages a candid and robust approach to overcoming obstacles by the front offices, coaches, and players.

Finally, political risk is not truly quantifiable, as Zegart put it. It involves perception, emotion, and intention. “No perfect algorithm” exists, she said.

The discussion was hosted by the Hoover Institution, the Freeman Spogli Institute, the Center for International and Security Cooperation, and the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Click this link to watch the complete discussion with Condoleezza Rice and Amy Zegart.

Media Contacts

Clifton B. Parker, Hoover Institution: 650-498-5205, cbparker@stanford.edu